Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

Monthly Archives: March 2009

New to the Twittersphere: Richard Brody of “The Front Row”

Martin Schneider writes:

Richard Brody, who covers movies from “The Front Row” in the blogs section of the New Yorker website, has taken up Twitter.

The main New Yorker/Twitter post has been updated accordingly.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Love in the Time of Grammar

Written and directed by Juan “Interroverti.”:http://emdashes.com/2008/09/winners-weve-got-winners.php Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

Area Twitterer Muses About Literary Magazine in 140 Characters or Fewer

Martin Schneider writes:

You guessed it, more New Yorker mentions from the aether! Let’s dive right in, shall we?

LeonardoZ Reading The New Yorker. Such a well written magazine. Wondering how even good mags can survive, specially in this economy.

cazelk It’s about time the New Yorker coughed up a solid 12,000 words on DFW. What do we pay them for again? Ohhhh right, I get it.

PaigeWiser The cover of the New Yorker magazine features Michelle Obama… with sleeves. Didn’t recognize her.

ericaceous Is there a bookstore in all of New York that carries anything by James Wood? He writes for the New Yorker, fer cripes sake!

judygoldberg I’m a finalists in this week’s New Yrker Caption Contest! I’ll just come right out and ask pls vote 4 me!!! http://tinyurl.com/anban5

mnreads listening to the new David Foster Wallace excerpt in the New Yorker, the read pronounces Edina, Minnesota wrong

nancheney David has the newly arrived New Yorker with the David Foster Wallace article. I had it first. grrrrrr.

alsolikelife: thinks David Denby’s New Yorker mumblecore piece reads like a teacher-parent consultation during PTA week: “Little Joey is making movies…”

wackjack I find it charming that The New Yorker still refers to publicists as press agents.

ErikHagen I like his beard so much that I want to draw pictures of it, and send them to the New Yorker to be published.

samduke left my new yorker at the taqueria only a 1/3 way through that epic DFW profile. 2nd time this week i’ve lost something before finishing it.

Cartoonless Captions Twitter: Inspired by TV on the Radio?

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Clocks Have Feelings Too

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

3/18: Catch the Simon Rich and Benjamin Nugent Event in Brooklyn

Martin Schneider writes:

There’s a fun event with two New Yorker luminaries on March 18 at the powerHouse Arena. From the press release:

The powerHouse Arena is pleased to invite you to a talk and reading

“Funny Because It’s True”

with Simon Rich and Benjamin Nugent

Moderated by Ben Greenman

Wednesday, March 18, 2009, 7-9PM

The powerHouse Arena

37 Main Street, Brooklyn

For more information: (718) 666-3049

RSVP: rsvp@powerhousearena.com

The powerHouse Arena invites you to a night of laughs, moderated by Ben Greenman, featuring Simon Rich, author of Free-Range Chickens and Ant Farm and Other Desperate Situations and Benjamin Nugent, author of American Nerd: The Story of My People.

About Free-Range Chickens

Simon Rich is a 24-year-old writer for Saturday Night Live, former president of The Harvard Lampoon, and author of the acclaimed book, Ant Farm (Random House, 2007). In his second book, Free-Range Chickens, Rich returns with another collection of humor pieces that mines more comedy from the absurdities of everyday life in our hopelessly terrifying world.

In short comic vignettes divided into sections such as “Growing Up,” “Going to Work,” “Relationships,” and a topic that has always puzzled him—”God,” Rich examines life’s biggest and smallest questions, from why people check their email every three minutes to God’s master plan for mankind.

In the nostalgic opening chapter, Rich recalls his fear of the Tooth Fairy (“Is there a face fairy?”) and his initial reaction to the “Got-your-nose” game (“Please just kill me. Better to die than to live the rest of my life as a monster”). He goes on to imagine office life as a “Choose Your Adventure Story” and later points out how we could all learn a lot about life and happiness by looking at the world through the eyes of free-range chickens. In his final chapter Rich imagines a conversation with God: Does God really have a plan for us? Yes, it turns out. Now if only He could remember what it was…

About American Nerd: The Story of My People

“American Nerd is very funny and consistently smart, but it’s also mildly controversial—I’m not sure I’ve ever seen these kinds of cogent, intuitively accurate arguments made about any ‘type’ of modern person. Benjamin Nugent is just weird enough to be absolutely right.”

—Chuck Klosterman, author of Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs

“The coolest book about nerds ever written. Heck, one of the coolest books ever written, period. Benjamin Nugent is the Richard Dawkins of geekdom. Outsiders of the world, this is required reading. Know your roots!” —Paul Feig, creator of Freaks and Geeks

“What everyone should be talking about…funny.”—GQ

Most people know a nerd when they see one but can’t define just what a nerd is. American Nerd: The Story of My People gives us the history of the concept of nerdiness and of the subcultures we consider nerdy. What makes Dr. Frankenstein the archetypal nerd? Where did the modern jock come from? When and how did being a self-described nerd become trendy? As the nerd emerged, vaguely formed, in the nineteenth century, and popped up again and again in college humor journals and sketch comedy, our culture obsessed over the designation.

Mixing research and reportage with autobiography, critically acclaimed writer Benjamin Nugent embarks on a fact-finding mission of the most entertaining variety. He seeks the best definition of nerd and illuminates the common ground between nerd subcultures that might seem unrelated: high-school debate team kids and ham radio enthusiasts, medieval re-enactors and pro-circuit Halo players. Why do the same people who like to work with computers also enjoy playing Dungeons & Dragons? How are those activities similar? This clever, enlightening book will appeal to the nerd (and anti-nerd) that lives inside all of us.

About the author:

Benjamin Nugent has written for The New York Times Magazine, Time, New York, and n+1. His first book, Elliott Smith and the Big Nothing, was published in 2004.

About the moderator:

Ben Greenman is an editor at The New Yorker and the author of several acclaimed books of fiction, including Superbad, Superworse, and A Circle is a Balloon and Compass Both: Stories About Human Love. His fiction, essays, and journalism have appeared in numerous publications, including The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Paris Review, Zoetrope: All Story, McSweeney’s, and Opium, and he has been widely anthologized.

His current projects include Correspondences, a limited edition handcrafted letterpress publication created by Hotel St. George Press and Please Step Back, a novel published by Melville House (due in April 2009). He is also a regular contributor to the music and psychology blog www.moistworks.com.

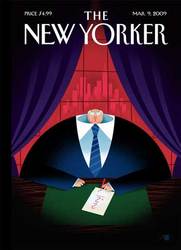

Best of the 03.09.09 Issue: Masters of the Universe

Martin Schneider writes:

Bob Staake’s takedown of Wall Street CEOs was on the cover. Features included Ian Parker’s report on Iceland’s economic collapse, D.T. Max’s look at the life of David Foster Wallace, and Sasha Frere-Jones’s appreciation of Lily Allen.

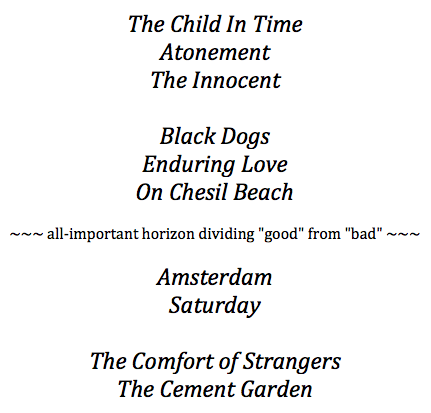

A Cheat Sheet for Ian McEwan, Confounding Modern “Master”

Martin Schneider writes:

Daniel Zalewski’s article “The Background Hum” clarified a few things in my mind about Ian McEwan. For the first time I realized that he mixes unlike traits. He’s either an exceptional writer who frequently writes bad books, or a pretty ordinary writer who had an unusually strong middle phase to his career. I favor the latter interpretation, but both will do.

Point being, let’s simplify, he’s a guy who’s written some very good books and some distinctly not-so-good books. This isn’t that unusual, I suppose, but McEwan’s kind of maxed out on his ability to do both things in the same career, which makes him cognitively difficult to get a handle on. He’s really incredibly famous—Britain’s “national author”—and very well-regarded, and he more or less escapes his proper share of abuse for the stinkers.

And by the way, no discredit to Zalewski, who repeatedly signals in the article that he understands this about McEwan, from the frank mention of Saturday‘s awkward contrivances to a friend’s “savage assessment” of McEwan’s prose to the nod to John Banville’s stinging review of Saturday in the New York Review of Books (link is courtesy of Mark Sarvas, a longtime McEwan detractor).*

Let me say now that I identify as a fan, and have for years, more or less. It’s precisely this enthusiastic self-identification that has made me notice how difficult some of his books are to defend.

Thing is, I had the luck to start with the good ones, beginning with his novella Black Dogs, which I liked a lot (even if, in retrospect, the ending is iffy). From there, in order: The Innocent, Amsterdam, Enduring Love, and Atonement, of which Amsterdam is the only true clunker of the bunch. Amsterdam is, I think, a bit scorned among McEwan enthusiasts because it won the Booker Prize, which was simply a mistake, they chose the wrong book, and it had the effect of making it difficult for his next book, Atonement, to get the support it deserved a few years later.

So, where was I? Right: Four winners in five books! I thought. Wow! This guy is the real deal! I was excited. After that, consistent with McEwan’s peculiar status, alluded to in the opening paragraph, came a surprise: the next five books I read (combining the very old and the very new) were close to an unmitigated disaster—and that group contained his best book.

To be precise: I read The Comfort of Strangers and The Cement Garden, earlier books, unremitting and unredeemable in my view. Then two newer ones: Saturday I had no choice but to abandon, and I rather liked the slight On Chesil Beach. And then, most recently, his midcareer masterpiece The Child in Time.

So, without further ado, here’s my scoresheet, ranked from good to bad with spaces to indicate significant differences in level:

A remark or two: I really liked The Innocent, and I’m surprised it doesn’t get mentioned more often. It’s the book of McEwan’s that rises for lack of obvious flaws. And Enduring Love is justly noted for its exceptional opening section; but the book does not, in truth, deliver on that promise. It’s still one of the good ones; that and On Chesil Beach are the weakest of the good group.

Parenthetically, as I prepared this list, it struck me how much of a problem McEwan has with cute or otherwise inorganic endings, which are often clever, tacked on, tricksy. Many of the books have brief “codas” or some other framing device that jars, intentionally, with the main part of the book. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

A clue to McEwan’s combination of successes and failures may lie in an impression of mine, at least, that he is especially beloved by a certain kind of reader who hasn’t always read that many top-notch novels; it’s hard to tell. McEwan is a little too good to be the “mere” poster boy for literary striving by the unsophisticated. And yet the people I know who have read really deeply (I am not counting myself in that group) don’t especially care for him.

I have a friend who amply qualifies as a person of that sort, and a few months ago we were discussing big-deal Anglo-American writers: Roth, McEwan, Mailer, D.F. Wallace, Vollmann, Amis, people like that. And at a certain point, apropos of nothing, implicitly addressing my McEwan fandom, she suddenly spat, “I mean—On Chesil Beach—” and I can’t rightly remember if her next utterance was “Ugh!” or “Come on!” but that should suffice to express her intended meaning.

On Chesil Beach? I thought. The thing’s not crap. It’s won awards. It was rather well turned. Small, slight, sure. But certainly pretty good.

And yet, and yet—in the meantime, I’ve come to understand her a little, I think. That business of being Britain’s “national author,” for one thing. Is it possible for a novelist to have a lamer identity? It’s worse than Michael Jackson’s insistence on being called the King of Pop. At this very moment McEwan, having completed a novel “about” 9/11, is off putting on the final touches of his novel about climate change. Saturday had few recognizable human beings, I don’t expect this next one to have any, either, for what I should think are obvious reasons.

Similarly, this business of disdaining literary values for scientific rigor…. it’s a bit much. The irony is that McEwan’s virtues are precisely literary ones, not intellectual ones.

For he does have virtues. His writing on the sentence level can be awfully good. And his reputation for a certain kind of sinister tension is well deserved. He’s got a little in common with Paul Auster, maybe—very good on the sentence level, with a good dose of high seriousness of an almost modernist kind, and with terrific narrative drive.

But he’s got something else. At his best, McEwan excels at a certain sort of wonderfully daring, original, and apt moment that is extraordinarily satisfying. He possesses the imagination to invent, sheerly invent, an audacious and yet very human detail that somehow brackets the artificiality of the rest of the novel and, indeed, of all fiction. The business with the balloon in Enduring Love is an example, but an even better one is the scene late in Black Dogs in which a serious confrontation in a French restaurant is unexpectedly undone by an absurdly misfired utterance. The Innocent and Atonement have something of this quality as well, situations of sufficient potency that they radiate worthiness to every other aspect of the book in question. What makes The Child in Time the best of McEwan’s books is that he was able to spread that effect across so much of the narrative, rather than isolate it to a single scene.

As I said before, McEwan had a helluva hot streak there in middle age. He’s written a short stack of very good books. You should go read those. And the rest? You’re on your own.

*) My memory of McEwan’s reception at The Elegant Variation was in error.

Sempé Fi (On Covers): Man of Means

_Pollux writes_:

In a gloomy office, darkened by heavy, purple curtains, in a building that towers high above the city, a captain of industry scribbles a modest sum. He does so with a stubby pencil on a sheet of elementary school paper, the kind that always tore when you rubbed it vigorously with an eraser. The pencil is red, suggesting bankruptcy, insolvency, and failure. “I start by creating the most basic shapes and then refine with details as I go,” the cover artist, “Bob Staake”:http://www.bobstaake.com/enter, “has remarked”:http://drawn.ca/2008/10/06/bob-staake-creates-a-cover-for-the-new-yorker/ in regards to his methods, and a significant detail in his March 9, 2009 cover for _The New Yorker_, called “Downsized,” is in the math problem being worked on by the dome-shaped businessman. Two plus two always equals four, but the executive maneuvers his pencil in a downward swing that suggests that he is writing anything but the number four. He’s getting the simple math problem wrong.

Something else is of course wrong too. The senior executive’s head rests uncomfortably on a Brobdingnagian body. He is disproportionate, a brontosaurus, all body with a tiny head. But is he also all body and no brains? The incorrect answer to the simple math problem seems to suggest this. The executive’s body, long nourished by three-martini lunches, bottom-line brunches, and profitability picnics, now fills a room oppressive with defeatism and doom, its curtains suggesting the closing act of a once powerful business. Behind and below him, a once mighty city now exists entirely in the red.

Perhaps it was put there by the kind of executive that Staake depicts, who has been feeding on lucrative payouts and salary increases, and whose head rests on titanic shoulders like an olive on a Boehm porcelain plate. The bodies of these executives are draped in red, white, and blue power ties and Kiton suits fitted by master tailors from Naples, their fingers trembling in the presence of witless tycoons. Staake’s executive may be an idiot, but he’s not going anywhere.

Staake’s basic shapes work well here. His executive is entrenched, the sheer volume and solidity of his frame filling up an office that remains _his_ office. He’s settled, probably unaware of the chaos outside, an archetypical fat cat and plutocrat, who doesn’t need a top hat and cigar to look and appear rich.

Staake’s “past _New Yorker_ covers”:http://www.bobstaake.com/nyer/reflection.shtml, from his “Minimalist Christmas” to his beautiful “Reflection,” remain beguiling and expressive, as simple as their components may be. His illustration style, in part inspired by artists of the 1930s such as “Adolphe Mouron Cassandre”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolphe_Mouron_Cassandre, “Jean Carlu”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Carlu, and “Donald Brun”:http://www.idesirevintageposters.com/brun.html, evokes the earliest _New Yorker_ covers, harkening back to another economic depression that terminated an era of heady prosperity and optimism.

However, as much as Staake’s style may be rooted in the machine age aesthetic of 1930s Art Deco, his theme is all too modern. The economy is on everyone’s mind, whether that mind is large or small. Staake’s image of reduced power (economic power, brain power, and political power) speaks to a society, that, as of 2009, has come to realize that our captains of industry have failed us, and failed us badly.