Martin Schneider writes:

We’re all accustomed to the perspective that The New Yorker is too precious, too pretentious, too serious, too self-absorbed, too too. We run into it all the time, it’s a balloon that seemingly demands puncture. People fall over themselves, clutching a needle.

It’s therefore instructive to enter “new yorker” as a search term on Twitter and see what people actually think.

Lot of enthusiasm out there. A lot.

It’s got to be about 5 positive comments for every dis. Maybe more than that. A few comments, chosen more or less at random:

i_Walt: Reading “The New Yorker” and listening to Verdi’s “Don Carlo.” Go out tonight? You must be joking.

abartelby: I need the latest New Yorker to read Ariel Levy’s essay but I don’t want to go out in the freezing rain so can someone please bring it over?

Sarahw224: I miss my new yorker already. Perhaps drawing room tonight or………..el prado?

subliminabubble: @mayaseiden i can’t even remember life before the new yorker! i’ve been reading it all day. thank you so much again!

I actually forget sometimes how much people love this magazine. It takes something as arbitrary as this to remind me.

Oh and also: people are having some trouble spelling Rahm Emanuel’s name.

Monthly Archives: February 2009

A Useful List: Who at The New Yorker Is Using Twitter?

Martin Schneider writes:

Well, it seems the world has finally caught up with us. We were Twittering as far back as the New Yorker Festival, which was nearly six months ago! Now it’s reached that juncture at which phenomena topple over into a phase of greater exposure (hmmm, could be a book in that), and now I’m running into it everywhere. We thought it was high time that Emdashes declared its intention to cover this properly.

So to start with: everyone reading this should know that The New Yorker is using Twitter with great vigor. The magazine’s Twitter is updated regularly and has useful information about new supplementary content on the website like podcasts or videos pretty much every day, usually several times a day.

Richard Brody, who mans “The Front Row” in the blogs section of the magazine’s website, is sending links to his posts on Twitter. The New Yorker Book Club uses its Twitter to link to recent posts and make announcements. The “News Desk” blog is using Twitter regularly. There are also feeds for the Book Bench and the New Yorker Festival.

I’ve done some modest research into New Yorker personnel who are tweeting away, and I’ve come up with the following list:

Sasha Frere-Jones 1

Michael Kupperman

Tad Friend

Bob Staake

Thessaly La Force

Susan Orlean

Liza Donnelly

Julia Suits

Ward Sutton

Sasha Frere-Jones 2 (probably defunct)

Dana Goodyear

Malcolm Gladwell

Erin Overbey (Emdashes regular)

Evan Osnos

Marisa Marchetto (protected updates)

Andy Borowitz

Daniel Zalewski

Lizzie Widdicombe

Lila Byock

Thessaly La Force wonders whether regular Twitterers ought to get extra credit. It’s a fair point. The list is now ordered by number of tweets sent, at least by a mid-March 2009 reckoning; I’ll try to order additions in that spirit.

There’s also the as-yet-empty Cartoon Lounge, apparently run by The New Yorker‘s PR wiz, Jamie Leifer.

A couple of comments: the indefatigable Sasha Frere-Jones tweets about as much as anyone I’ve encountered. Tad Friend tweets quite a bit as well. Dana Goodyear is just starting out, and after a few good weeks, Gladwell may have lost interest—we hope not!

There’s also the charming newyorkerest, run by an enterprising San Franciscan. The purpose of newyorkerest is to isolate the best article in each issue. We’d like to give them a warm welcome to the heady world of New Yorker commentary. What we like most about newyorkerest is that it is all about celebrating genuine achievement; we are too, hence we celebrate newyorkerest.

Oh, here are some Emdashes-related Twitters: Emdashes, Martin, Benjamin, Print magazine.

A final note: We believe that this information—who at The New Yorker indulges in the occasional tweet—is intended for public consumption; otherwise we would not post it. It’s not our intention to catch anyone out or make anyone uncomfortable. So if anyone would like to see his or her Twitter status removed from this list, we’ll only be too glad to do so. Of course, if you’re a New Yorker contributor whose Twitter feed we haven’t discovered (yet), by all means email us and we’ll add it to the list so everyone we know will know how best to follow your interesting activities.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Every Day is National Punctuation Day

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

DC Gossipmonger Wonkette Twits “Bemonocoled” Mag

Martin Schneider writes:

Just so you know: Much to David Denby’s presumed dismay, Wonkette directs its snark at the current issue. They like the Ivan Brunetti cover, though. As do I!

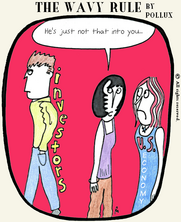

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: It’s Not You, It’s Me… Okay, It Is You

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Usonia Dreamin’

Yes, I really do sleep in a Wikipedia sweater and have dreams that anyone can edit. Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

Boffo Barthelme Bio–Update

Benjamin Chambers writes:

No doubt because we covered the publication of a new bio on Donald Barthelme a couple of weeks ago, Louis Menand has a long, juicy piece on the man and his biography in the February 23rd issue of The New Yorker. There’s even audio of Menand discussing it.

Meanwhile, Kyle Smith used the occasion of the bio, disappointingly, to diss Barthelme in The Wall Street Journal as at best an author who never lived up to this potential. There’s no question that Barthelme could be frustratingly obscure, but most writers produce dross as well as masterworks; the best, like Barthelme, display a willingness to keep trying. When Barthelme was “on,” he was funny, sharp, and unpredictable, a true pioneer. I’m thinking in particular of “The School,” which appeared in The New Yorker in 1974, and “The President,” from 1964, but there’s many more. Even his minor stories furnish bright flashes that still dazzle, though I suppose that anyone who dislikes even minor deviations from straight realism probably wouldn’t agree.

What puzzles me most about Smith’s assessment of Barthelme is actually something that’s present even in Menand’s piece: the assumption that Barthelme’s work must somehow be accounted for, the dust on his trophies measured to see if it’s commensurate with his achievements. I find this attitude startling, though perhaps it’s only because Barthelme was one of the writers who sparked my own interest in literary fiction. I simply don’t see him as a writer whose star has waned in the years since his death; to my mind, his constellation has never dipped below the horizon.

In his fascinating book The Delighted States (which is coincidentally as much sui generis as Barthelme’s work), Adam Thirlwell argues that while Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy has no obvious or immediate heirs, it’s had a lasting and discernible influence on later fiction. I suspect the same will be said of Barthelme in spite of those who, like Smith, wish to dismiss his work as a dead-end: irreducibly original, it will be a well to which many writers will return again and again to study its mastery of tone and style, its ambition, and its sheer joie de vivre.

Drama Review: Neil LaBute’s “Wrecks,” Bush Theatre, London

Martin Schneider writes:

Emdashes is a supporter of all forms of live performance, particularly theater, music, and comedy. Friend of Emdashes (and occasional contributor) Quin Browne clearly shares this credo; indeed, she opens her review of the London production of Neil LaBute’s Wrecks with an identical declaration. Quin helped Emdashes cover the 2007 New Yorker Festival, when she reported on Neil LaBute’s lively session with John Lahr. We consider this post a felicitous continuation of that one. Enjoy.

~

There really is nothing like theater.

I had seen Wrecks, written and directed by Neil LaBute, at the Public Theater in New York when it premiered there. I paid for my ticket, I sat in the back row, and I spent the evening on the edge of my seat, leaning forward, chin on hands, while Ed Harris charmed all of us, leading us down the darkish path of Ed Carr, a man who had just lost his beloved wife, JoJo.

When I was notified by the Bush Theatre in London it would be playing during my time here, my actor friend Loo and I decided to see it, so I could enjoy the play again, and she could take it in for the first time. LaBute wasn’t directing, but it was still one of his works, and I do like my LaBute.

The U.K. version starred Robert Glenister and was directed by the Bush’s artistic director, Josie Rourke. Once again, it was a stark, simple set: you walk in, and you are confronted by a casket, nothing more.

It tips you off that this will not be your average play.

And that it isn’t. It’s a 75-minute monologue, delivered by Ed, who takes your hand and leads you down the path of his life, which includes his being raised in foster homes, his discovery of his JoJo, and their courtship and subsequent life together. He tells of his passion for restoring old wrecked classic cars and of their success turning it into a profitable business. He touches lightly on their two daughters and JoJo’s two sons from her previous marriage. The whole focus of his life, it seems, was JoJo, the business—oh, and his almost equally beloved cigarettes, which he puffs all through the show— Wait! You mind if he smokes? You would deny a grieving widower anything in his time of sorrow?

I’m a huge fan of LaBute’s. Unlike some, I don’t find him to be misogynistic in any way. I actually think his men tend to come off as the cads, the wimps, the fearful ones, the ones who don’t quite get what life is all about, who make promises they will never keep. I have maintained that his work has a solid bedrock built on the subject of love—how we abuse it, use it, discard it, steal, cheat, lie, and destroy other people in its name. This particular play is an excellent example of that theory: what we do for love.

This is a lovely, rich, intense monologue, one that holds you steady for the full 75 minutes, a stream-of-consciousness discussion, occasionally referring to the sounds of his other “self” and the other voices that are occasionally piped in, that nice way he has of delivering it, a twist that makes you go, “WTF??” in the last few moments of the show. I heard a nice big gasp from the audience, showing it had been pulled in and rightfully shocked by that moment.

After watching Harris, I was a bit concerned. I mean, Ed Harris? He has you from the first moment with his “join me for a bit of soul searching” smile and those eyes that are a richer blue than you can imagine, crinkling in laughter and smiles, something deep and sad in them the entire time.

Glenister didn’t disappoint. He had a different take on his character, a different delivery, a different pronunciation of “mimeograph” (these things matter!). But he, too, pulled you in, took you with him in his woven storyline; even knowing the twist, I still experienced a slight shock.

The two productions were alike in set, yet vastly different. The Harris work had a shiny black casket, and a very American feel to the funeral setting. The Bush set design is a bit more British: a wood casket, smaller flowers, and a photo of the beloved. Glenister is a shade more casual in his dress, Harris being very crisp in his mourner’s attire. The Bush only seats around 86 people, so there was a wonderful intimate feeling you didn’t get from the Public.

I was pleased by Glenister’s dialect—he sounded very American, and an unconvincing American dialect has caused issues in other London productions of American plays. He carried the flat sound of the Midwest effectively, and I didn’t find it jarring or annoying at all, just, well, American.

LaBute’s script is woven with humor, loss, pride, and that evasive love. His words cling to you, attached to your memory after you’ve left the theater. The lines can soar past, then bounce back to hit you with a solid “THWACK!” Afterward, Loo and I went to a restaurant and I overheard a group discussing the play, discussing with awe and passion their version of four words Ed whispers to his dying Jo (which we never hear). It was interesting to hear other viewpoints, and a compliment to the playwright that the dinner discussion was not what to order but the play and what! and why! and wow!

I highly recommend this play, should you have a chance to see it. London theater remains very affordable; these tickets were less than 18 pounds. The Bush is an amazing venue, and the subject of a petition signing to keep it from closing last year.

Ed Carr is a multilayered, diverse, complex, controlling man who never gave up in his desire to find and keep love. He would do anything for love—anything.

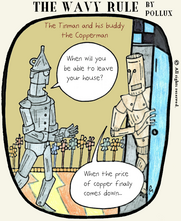

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Copper Sharks

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

Is Harold Ross a Model for Today’s Strapped Magazine Publishers?

Martin Schneider writes:

It’s common to hear nowadays that the American magazine is doomed. Hearst’s Cathie Black begs to differ, invoking the example of the first years of The New Yorker:

In 1933, a year when every dollar mattered, The New Yorker’s founders, Harold Ross and Raoul Fleischmann, published a Code of Ideals for their magazine. Ignoring the economy, they boldly announced, “Great advertising mediums are operated for the reader first, for profits second.” They got their priorities right: When you truly serve the reader, the advertisers will come.

Those are bracing and inspiring words to hear. You have to admire their guts. No matter how things get, I tend to agree with Black that no matter how bad circumstances get, the industry of selling bits of colored paper with words on them on a weekly, semi-weekly, or monthly basis—is not going to perish anytime soon. I hope I’m right!