Benjamin Chambers writes:

Emily says today is Emdashes’ fifth anniversary. In celebration, I offer the following cartoon by Claude Smith, from the June 24, 1967 issue of our favorite magazine. I like to think the group is looking at an early mock-up of this blog. (Click for larger view.)

P.S. You can also consider it an entry in Martin’s series of Mad Men Files columns.

Author Archives: Benjamin

Holy Last-Minute Gift, Der Fledermausmann!

Benjamin Chambers writes:

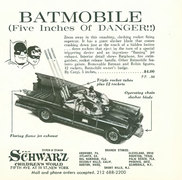

What would have been the perfect, last-minute gift for someone on your holiday shopping list in 1966?

I’m betting it would’ve been the Batmobile seen on p. 185 of the October 1, 1966 issue of The New Yorker. (Click on the image below for a larger view.)

I was lucky enough to own one of these (though I didn’t get it until 1971 or so), and I can attest that it was the coolest toy car ever made. I quickly lost the “rockets”, but nothing ever dulled the joy of the car’s sleek lines, the futuristic windshield, or the chain-snapping blade that would pop out of the hood.

Curious to see if the Batman ever showed up in The Complete New Yorker, I was pleased to see that he did. I’ll have more to say about this at another time, but my favorite find was the Everett Opie cartoon below, from the June 24, 1967 issue. (Again, click on the image for a larger view.)

Naturally, the cartoon made me want to look into the Strauss operetta, “Die Fledermaus,” which I’d heard of, but never seen. I was amused to learn from Wikipedia that the gist of the finale is, “Oh bat, oh bat, at last let thy victim escape!”

Priceless!

That Thunderbird Touch

_Benjamin Chambers writes_:

Cruising through The Complete New Yorker (TCNY) the other day—though without a unique Safety-convenience Panel—I ran across a great ad for the Ford Thunderbird on page 5 of the December 25, 1965 issue (click image for larger view):

It’s interesting how explicitly the advertisers (Mad Men, anyone?) tried to evoke the romance and cachet of flight: the sheer novelty of having an overhead, “Safety-convenience” instrument panel was used to connote the complexity of the cockpit, and the driver was shown wearing, of all things, a pilot’s uniform. Drive this car, in other words, and you will be captain of your destiny, far from earthly cares … Hard to imagine that idea resonating with anyone today who’s flown coach.

However, I was intrigued by two of the car’s new features: the Stereo-Sonic tape system, and the “automatic Highway Pilot speed control option.” Maybe I’m showing my age, but I had no idea what Stereo-Sonic tapes were, and was surprised to learn they were 8-Track tapes. I hadn’t realized they were introduced so early. (According to Wikipedia, Ford introduced 8-track players in most of its automobile lines in September 1965.)

The mention of the “Highway Pilot speed control option” made me wonder when cruise control was first introduced. Turns out it’s been around since the 1910s (!), though the modern version first appeared in a 1958 Chrysler.

Apparently, the guy who invented the modern version did so after he got tired of the way his employer kept speeding up and slowing down when he was talking as they drove along together. Who knew that highly-useful invention was born of such deep irritation? Maybe that’s why the driver shown in the ad has no passengers. Wouldn’t want to spoil the illusion of peaceful command by including insubordinates just itching to fix your wagon …

The Importance of Knowing What You’re Good At

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Reading some old hard-copy issues of The New Yorker dating from the 1990s, I ran across the “Postscript” piece by Lee Lorenz on George Price, from the January 30, 1995 issue.

I grew up with Price’s angular cartoons and his quirkily dry sense of humor— and since the guy did over 1,200 drawings for the magazine between 1929 and his death, many people alive today can say the same—so I was stunned to learn that “only one [of his cartoons], amazingly, was based on an idea of his own.”

What Price was good at was drawing, and so he used punchlines that were supplied for him. It wasn’t that uncommon to use gag writers, but I’d guess the frequency with which he did so was, and the way the results do seem to be so of-a-piece, as if the punchlines and the drawings really were the product of a single mind.

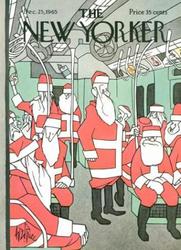

It’s telling, I think, that the one drawing that was based on his own idea was a sight gag, and didn’t have a punchline. It appeared on the cover of the December 25, 1965 issue, and can be seen below. (Click the link at left to find it on The Cartoon Bank; click on the image below to see a larger version.)

The same 1995 issue of TNY that contained the homage to Price also featured David Owen’s profile of software entrepreneur and art patron Peter Norton (Norton Utilities, anyone?). I read the profile at the time the issue came out, and for the past 15 years, it has stood out in my memory as an excellent portrait of a bright, highly unusual man. One of the amusing things in the piece:

Nerd tycoons differ from robber barons … If there had been no such thing as petroleum, John D. Rockefeller would surely have found some other means of becoming stupefyingly wealthy. But if there had been no computers, what would have happened to guys like [Bill] Gates and Norton? Norton suspects that he might have ended up either as “an angry cab-driver with a Ph.D.” or as a paper-shuffling minion of some faceless corporation, much as his father was. The fact that big companies were beginning to use computers at the very moment Norton entered the job market was a hugely propitious accident for him— like becoming a teen-ager in the year they invented French-kissing.

For the Next Style Issue

Benjamin Chambers writes:

With a few exceptions, The New Yorker has never gone in much for featuring tidbits from its past issues, but here’s one from a short Talk piece by Ian Frazier from the October 10, 1977 issue that should be highlighted in the next Style issue.

Attending a Parsons-New School lecture called “Fashion for the Consumer,” Frazier found “the most interesting part” was the slides shown by Dorothy Waxman of fashions seen on the street. Here’s the punchline:

One of the slides was of a woman stepping off a curb holding a little girl by the hand. “‘Look at this beautiful woman!’ said Dorothy Waxman. ‘Look at the stunning neutral palette of colors she has chosen—the hat just a slightly brighter shade than the jacket. The colors aren’t flashy, but they really come alive. And look at that beautiful little blond girl. What a wonderful accessory!'”

New Yorker Fiction Podcast Continues on its Royal Way

Benjamin Chambers writes:

On the eve of the release of The New Yorker’s fiction issue, it seems like the right time to mention (again) how amazing the magazine’s fiction podcasts are. Back in January, I reviewed the 2008 podcasts and even threw in a plug for this year’s reading by Thomas McGuane of James Salter’s chilling story, “Last Night.”

Now there’s three more treats waiting for the unwary:

- First, there’s Joyce Carol Oates reading Eudora Welty’s searing “Where Is that Voice Coming From?” from the July 6, 1963 issue. To my mind, Oates’ Yankee accent can’t do Welty justice, but the narrative’s acid power still leaks through. If it drives listeners to read the story on their own, then the podcast will have done its job.

- I’ve not read much Isaac Bashevis Singer, so it was a special treat to hear Nathan Englander read Singer’s “Disguised,” from the September 22, 1986 issue, about a woman who searches for the man who inexplicably abandoned her only to find he’s taken up an unthinkable new life without her. A marvel of economy, the story’s simply delightful, and Englander’s reading enhances it.

- After a great performance last September reading Stephanie Vaughn’s “Dog Heaven” from January 1989, Tobias Wolff returned to read another classic (albeit better-known): “Emergency,” by Denis Johnson, first published in the magazine on September 16, 1991 and later collected in Johnson’s book Jesus’ Son.

Bottom line: you can’t go wrong with any of these. Go forth and listen!

Polansky’s Story Has Leg

Benjamin Chambers writes:

A couple of weeks ago, I used the random number generator to find a 2004 story from The New Yorker that I’d never read before by Yoko Ogawa, “The Cafeteria in the Evening and the Pool in the Rain.” This week, it took me to to the January 24, 1994 issue of TNY and Steven Polansky’s story, “Leg.”

In the story (and yeah, there are spoilers coming), Dave Long is a forty-four-year-old whose main trouble appears to be his thirteen-year-old son Randy’s new and implacable anger, a by-product of adolescence, which he spews at Dave every chance he gets. Even Dave’s liking for reading is a target:

If Dave sent Randy to his room or otherwise disciplined him … Randy would say, in his cruelest, most hateful voice, “Why don’t you just go read a book, Mr. Reading Man, Mr. Vocabulary. Go pray, you praying mantis.”

Sliding into third in a church softball game, Dave skins his leg from knee to ankle. Except for basic First Aid, he neglects the injury. It gets infected, leaks pus all over his pants, and he spends much of the story lying on the kitchen floor or on the couch with his foot elevated until the pain is so bad he can no longer stand. Four people tell him to go see the doctor (including the doctor himself, who warns of gangrene, sepsis, and amputation); Dave cheerfully deflects each request. He finally capitulates when his son asks him to go—too late, however, to save his leg.

It’s hard to understand why this apparently normal, well-meaning man would allow a minor injury to fester and keep him home from work, why he’d lie to others in order to avoid going to the doctor. But we get our first clue shortly after he gets home the night of the softball game, hours after he’s hurt himself.

We already understand that the scrape on his leg isn’t ordinary. He’s tried staunching the blood first with a whole roll of toilet paper, then gauze. He’s even applied a dish towel fresh from boiling water to the wound.

Then he sat down on the kitchen floor, his left leg stretched out before him, and prayed.

His praying was rarely premeditated or formal. Most often it was a phototropic sort of turn, a moment in which he gave thanks or stilled himself to listen for guidance. He shied from petitionary prayer. With all he had, it felt scurvy—scriptural commendation notwithstanding—to ask for more. This night, his leg hurting to the bone, he permitted himself a request.

“Father” he said quietly, “please help me to see what I can do for Randy. He is in great pain. I love him. If it is your will, show me what I might do to bring him peace.”

His request is surprising, and gives us a sense of the line he’s going to take: his injury is of no importance, except, perhaps, as a means to healing his relationship with his son and with God.

I can’t prove it, but I suspect Dave’s relationship with God matters more to him than Randy does, though the author, like Dave himself, keeps this fact low-key. For example, I had to re-read the story to catch a second meaning when the left fielder, a pastor, calls to Dave as he’s caught between bases, “You’re dead, man.” Dave smiles at this, and then reflects, “But Pastor Jeff had the straight truth here: Dave was dead. To rights. Dave had been fast, but he was forty-four now, and he was too slow to pull this sort of stunt.”

The awkward syncopation of “Dave was dead. To rights,” is meant (clumsily I think), to call attention to Dave’s real problem. It’s not Randy: it’s the fact that he is in some way, spiritually, or perhaps in the afterlife, dead.

And then there’s the pun wrapped up in the “straight” (or strait) truth. For the very morning of the softball game, Dave and his own pastor had discussed Matthew 7:13-14, a passage that

… Dave had lately found compelling and vexing. “Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.”

Dave, pressed by his pastor, defines the “narrow gate” variously as severe, pinched, straitened, exclusive, simple, severe. Hence the extra oomph when the left fielder is described as having the “straight [strait] truth.”

Later, when Dave’s suppurating wound has confined him to the couch, he tells his pastor that he thinks that some of the faithful (meaning himself) need a prescriptive theology: “We’re sloppy. We’re slack. We’re smug. We’re just flat-out disappointing. You got to whip us into shape, or we embarrass ourselves. And each other.”

In this context, it’s possible that Dave sees his son Randy’s constant insults as a kind of necessary “straitening,” a scarifying test. By testing himself in even harsher terms and allowing his infected wound to inflict him with unrelenting pain, Dave is pushing himself through the “narrow gate” into a new life.

Which explains why Dave does not spend his time moaning or complaining. Instead, his wife describes him as “calm and reasonable and in amazingly good spirits.” When his family joins him in the living room to eat dinner and watch television, we are told that “Dave, who was light-headed and running a low-grade fever, was happy.” He has the serenity of the saved.

Dave relies on his faith to resolve his tension with Randy, yet without taking any direct action himself, a device that definitely sets the story apart. After all, it’s not everyone who would address the storms of his child’s adolescence with a strict and self-lacerating commitment to avoiding medical care, completely certain that rapprochement will result.

Slightly Less Recent New Yorker Fiction Roundup

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Continuing in a format I adopted last week to provide mini-reviews of some recent stories from The New Yorker, I reach slightly farther back this week and throw in a more recent story by J.G. Ballard for good measure. [Again, watch out for spoilers below.]

Let’s begin, in fact, with the J.G. Ballard’s “The Autobiography of J.G.B.,” from the May 11, 2009 issue.

Plot: The main character, B (whom we are invited, because of the title, to associate with the author), wakes one day to find a world in which all other human beings have vanished. With little trouble, he adjusts and prepares for his own survival.

The Story’s Final Line: “Thus the year ended peacefully, and B was ready to begin his true work.”

Verdict: Ballard’s tricky, and his predilection for stories that blur the boundaries between autobiography and fiction don’t help a reader feel certain of his or her ground. He’s also very fond of post-apocalyptic worlds. But it’s hard not to read this very brief story, published posthumously after Ballard’s death on April 19th, as a comment about his own impending death. In a characteristically surprising reversal, J.G.B. doesn’t die, leaving teeming billions behind; instead, he alone is left to soldier on in the afterworld, while everyone else dies/vanishes. In this light, the story is actually quite poignant, though not weighty. (BTW, this is Ballard’s first appearance in TNY.)

Bonus Content: Tom Shone, author of a profile of Ballard that appeared in TNY in 1997, is interviewed in the May 11, 2009 issue of The New Yorker Out Loud.

“The Color of Shadows,” by Colm TóibÃn, which appeared in the April 13, 2009 issue, also hinges heavily on its final lines, as the Ballard story does.

Plot: Paul, a middle-aged man, returns home to Enniscorthy from Dublin after his aunt Josie, who raised him, falls and can no longer remain at home. He arranges for her to stay in an assisted living facility and visits her regularly until her death. Before she dies, however, she extracts a promise from him that he will not ever visit his mother.

Verdict: I won’t quote the final paragraph at length here, because it’s one of the few moments (if not the only one) in the story where the author allows himself to stray from a ruthlessly-restrained narrative long enough to suggest emotion. It works on Ernest Hemingway’s principle that the core of a story should remain submerged, like the bulk of an iceberg, while the visible portion (above the water, so to speak) should merely suggest the whole. Over the course of the story the back story becomes a little clearer; and though Josie raised Paul and Paul doesn’t remember his mother, his relationship with his aunt is more strongly characterized by duty than by love. You know he’ll keep his promise never to visit his mother, but it’s also clear he’s only beginning to realize what that will cost him. I can’t say the story’s to my taste, but it’s certainly well-made.

Similarly, the ending serves as the fulcrum of Craig Raine’s “Julia and Byron,” from the March 30, 2009 issue. (The image that keeps coming to mind to describe these author’s reliance on their stories’ closing words is that of the “slingshot effect,” where NASA used the gravitational pull of the outer planets to “sling” the Voyager spacecraft ever farther out into the solar system.)

Plot: Julia and Byron have been married a long time; happily, in his view, evidently not-so-happily in hers. At 62, she develops cancer for which she agrees to undertake radical treatments at the hands of a cynical doctor who has no ear for her sense of whimsy or personal hazard. She dies, horribly, in her husband’s arms, and he is undone by grief — for a while.

Final lines: “For two years he was a grief Automat, crying unstoppably at the mention of her name. Then he remarried–a younger woman–and was a difficult husband.”

Verdict: For my money, “Julia and Byron” is a more interesting read than “The Color of Shadows” because it’s difficult, for one, to guess where it’s going (Byron is introduced abruptly midway through, when Julia’s nearly dead); and for another, its surprising references to verse by A.A. Milne (quoted first mischievously by Julia, then by maudlin Byron). Julia’s the one you regret not getting to know, and that may be because Byron is histrionic, simple, while Julia appears unknowable and full of contradictions. Still, the final lines reduce the story to a homily on the impermanence of grief, or the permanent tendency of human beings to forget even their grandest passions. It’s not clear Raine meant for his final line to cast such a long shadow over the story (it’s quite possible he only meant it to be a comment on Byron), but either way, it mars it.

Finally, in “Visitation,” by Brad Watson, which appeared in the April 6, 2009 issue, we have exactly the opposite phenomenon: it’s not the last lines that sum everything up, it’s the opening paragraph.

Plot: Loomis is recently divorced and is in town visiting his young son. His entire trouble is encapsulated in the story’s opening lines: he’s a pessimist, and his depressed outlook saps the joy from his life, leaving him directionless and cut off from others. (Tellingly, he’s the only character in the story who’s given a name by the author. Loomis’ son is always “the boy,” etc.) The story consists of several episodes in which Loomis is threatened by an inexplicable outside world or irretrievably excluded from the happy world of others. The one person who breaks through to him, briefly, is a “Gypsy” woman who reads his palm and his character with the authority of a Delphic oracle, causing him to lapse into … well, pessimism and despair.

That Great First Paragraph:

Loomis had never believed that line about the quality of despair being that it was unaware of being despair. He’d been painfully aware of his own despair for most of his life. Most of his troubles had come from attempts to deny the essential hopelessness in his nature. To believe in the viability of nothing, finally, was socially unacceptable, and he had tried to adapt, to pass as a believer, a hoper. He had taken prescription medicine, engaged in periods of vigorous, cleansing exercise, declared his satisfaction with any number of fatuous jobs and foolish relationships. Then one day he’d decided that he should marry, have a child, and he told himself that if one was open-minded these things could lead to a kind of contentment, if not to exuberant happiness. That’s why Loomis was in the fix he was in now.

Verdict: I confess that I don’t have a lot of patience with stories whose entire narrative drive is carried by a vaguely unhappy middle-class white man who feels isolated and trapped, and his stasis is the point. The ironic humor of the opening paragraph peters out, unfortunately; and though the “visitation” by the so-called Gypsy is intense and promises some kind of transcendence, the narrator’s left back where he started.

But check these stories out for yourselves and see if you agree.

Recent New Yorker Fiction Roundup

Benjamin Chambers writes:

I’ve been catching up on recent New Yorker stories, so I thought I’d provide a quick-ish summary of them, using a model I ripped off from Martin. [Warning: there are spoilers below.]

“The Slows,” by Gail Hareven (trans. Yaacov Jeffrey Green), May 4, 2009

Plot: An anthropologist has one last encounter with one of the “savages” he has studied for years, though he finds her kind repellent. The “savages,” like the anthropologist, are human, but they have refused a technique that greatly speeds human growth and development, setting them apart.

Key Quote:

No doubt the savages were a riddle that science had not yet managed to solve, and, the way things seemed now, it never would be solved. According to the laws of nature, every species should seek to multiply and expand, but for some reason this one appeared to aspire to wipe itself out. Actually, not only itself but also the whole human race. Slowness was an ideology, but not only an ideology. As strange as it sounds, it was a culture, a culture similar to that of our forefathers.

Verdict: You’ll like it if you don’t mind reductive parables disguised as fiction: humans invariably find reasons to justify their appetite for genocide.

“Vast Hell,” by Guillermo Martínez (trans. Alberto Manguel), April 27, 2009

Plot: A mysterious stranger arrives in a small (Argentinian?) town and is presumed to be having an affair with the wife of a barber. When the wife and stranger disappear, village gossips presume foul play. Efforts to find their bodies, however, unearth an unexpected tragedy.

Teaser Quote:

The horror made me wander from one place to another; I wasn’t able to think, I wasn’t able to understand, until I saw a back riddled with bullets and, farther away, a blindfolded head. Then I realized what it was. I looked at the inspector and saw that he, too, had understood, and he ordered us to stay where we were, not to move, and went back into town to get instructions.

Verdict: Absorbing, economical, but too abrupt. The implications of the surprise discovery at the end need more time to unfold, to become something more than an unpleasant event that touches no one.

Interesting Fact:Judging from Wikipedia’s entry on Martínez, this story is taken from a collection he published way back in 1989. (It’s his first to appear in TNY, as is Hareven’s piece.)

“A Tiny Feast,” by Chris Adrian, April 20, 2009

Plot: The changeling boy stolen by the fairies Oberon and Titania develops leukemia; uncomprehending, they must shepherd him through the horror of chemotherapy.

Key Quote:

Alice cocked her head. She did not hear exactly what Titania was saying. Everything was filtered through the same normalizing glamour that hid the light in Titania’s face, that gave her splendid gown the appearance of a tracksuit, that had made the boy appear clothed when they brought him in, when in fact he had been as naked as the day he was born. The same spell made it appear that he had a name, though his parents had only ever called him Boy, never having learned his mortal name, because he was the only boy under the hill. The same spell sustained the impression that Titania worked as a hairdresser, and that Oberon owned an organic orchard, and that their names were Trudy and Bob.

Verdict: Delightful though sad; a bit reminiscent of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s “Elphenor and Weasel.” The story only falters in its final paragraph, where the fairies are at a loss and the final lines seem insufficient to bring the piece to a close. [UPDATE: I see I didn’t make it clear that “Tiny Feast” is really an amazing story, and definitely worth reading.]

Interesting Facts:Adrian is a graduate of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, works as an emergency room pediatrician in Boston, and is this year supposed to get a degree from Harvard Divinity School. The man’s an overachiever; we’re lucky he’s a writer. I can’t wait to read the other three stories of his that have appeared in TNY.

Ogawa’s Cafeteria in the Evening

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Following Martin’s example, when he used the random number generator to select Profiles to read from The New Yorker’s vast archives (his first was a three-part series on Chicago by A. J. Liebling from 1952), I decided to use it to find a short story to read from the archives.

The random number generator came up with “2004” (year “79” out of 84) and then the “36th” story out of 54 published that year: Yoko Ogawa’s story, “The Cafeteria in the Evening and a Pool in the Rain.”

I’d not heard of Ogawa before. She’s had two stories appear in TNY (both translated by Stephen Snyder), the most recent in 2005. I’m always curious about what tides of opinion and chance conspire to make a writer a frequent contributor to the magazine or a short-lived one, and of course it’s usually impossible to know. However, according to Ogawa’s Wikipedia entry, very little of her work has appeared English, although she’s written quite a lot. (Obviously, Snyder was trying to rectify that, so it’s not clear if the problem was really one of supply.)

In any case, the story’s narrator is a young woman in her early 20s who is about to marry an older man (“the difference in our ages was excessive”). They have selected a house together, partly to accommodate their dog, Juju. The woman is living in the house alone for the three weeks prior to their wedding, getting it ready, when a man and his 3-1/2-year-old son visit one afternoon.

The man’s behavior is odd and she takes him at first for a missionary before realizing her mistake. “Are you suffering some anguish?” he asks “abruptly.” Rather than turn him out on his ear, she considers the question seriously. He leaves after she finally observes that she doesn’t feel like answering:

Do I absolutely have to answer? I’m not sure I see any link between you and me and your question. I’m here, you’re there, and the question is floating between us—and I don’t see any reason to change anything about that situation. It’s like the rain falling without a thought for the dog’s feelings.”

The guy repeats her simile thoughtfully and then says, “I think you could say that’s a perfect response, and I don’t need to bother you anymore. We’ll be going now. Goodbye.”

She runs into the pair again while out walking her dog. The man’s staring in the window at the behind-the-scenes operation of the highly-mechanized school cafeteria, which prepares lunches daily for over 1,000 children. Once again, they have a slightly bizarre conversation.

She finds herself drawn to him, hypnotized a little by the stories he tells, and she begins to look for him when she’s out walking. It’s never clear what he does for a living though he speaks as though he has territory to cover, and at the end, that he and his son are “moving on” to another town the next day. (Because of this, he finally appears to be a bit unreal, a kind of good angel/therapist designed by the author to confront the character with riddles that will help her resolve her own internal–unstated and possibly unacknowledged–doubts.) The lack of detail about the narrator and the ordinariness of those that are supplied contrast strongly with the precise detail of the man’s own stories, making the piece reminiscent of Haruki Murakami’s work, and similarly intriguing.

The things the man says are dense and obscure as parables, and they nearly defeated me. (As the British novelist Nicholas Mosley says in his autobiography, Efforts at Truth, “The power of parables is that even then you still have to figure out everything for yourself.”) I ended up hanging the meaning of the story on its final paragraph:

[The man and his son] walked off in the fading light. Juju and I stood watching them until they became a tiny point in the distance and then vanished. I suddenly wanted to read my ‘Good night’ telegram [from my fiancé] one more time. I could feel the exact texture of the paper, see the letters, feel the air of the night it had arrived. I wanted to read it over and over, until the words melted away. Tightening my grip on the chain, I began to run in the opposite direction.

In other words, the “anguish” she’s been feeling is apprehension over her impending marriage. The man represents, in part, a different life, different choices. In the end, she runs toward marriage and away from the disconnected anomie represented by the man and his son. His mysterious “work” is done because he knows (how?) that she’s resolved her doubts.

Overall rating: worth a look, especially since Ogawa’s not a household name.