Emily Gordon writes:

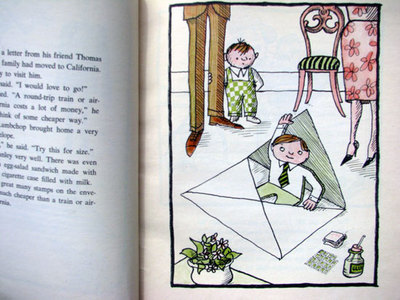

I just discovered The Apple and the Egg, a handsome blog about design and illustration for children’s books. The entry linked here is about one of the great heroic tales of our age (or, in my case, slightly before my age), Flat Stanley by Jeff Brown. Although I’m loath to denounce anyone these days, especially hardworking illustrators and anyone to do with children’s books, I can’t support the terrible decision to replace Tomi Ungerer’s bold, winning, exuberant drawings. You’ll have to turn to Powell’s and eBay to buy the original, and it’ll be yellowed and will possibly have been dropped in the bathtub once or twice. But it’s worth it! For now, The Apple and the Egg will give you the quick fix you need.

Unrelated, and entirely three-dimensional (or even four, since it’s about time): Colin Quinn’s advice for comics on Broadway.

Monthly Archives: February 2011

New Yorkers: Excellent & Free French Festival Starts Today!

Martin Schneider writes:

There’s a very intriguing festival starting today and running through Saturday in New York City for those who can attend. (I expect to attend multiple events myself. If you spot me, by all means say hello!)

It’s the Festival of New French Writing at NYU’s Hemmerdinger Hall on Washington Square. All events are free of charge, all events will interestingly pair a prominent French intellectual or writer with an American counterpart, and all in attendance will receive a free Renault Wind Gordini. (One of these facts is not true, but I’m not telling which.)

My knowledge of recent French writing is pretty paltry (starts with Houellebecq and ends with Carrère, neither of whom will attend), but if the French luminaries are as prominent as the Americans (all of whose names should be familiar to the typical Emdashes reader), the festival should be wall-to-wall terrific.

I am excited to see the brilliant and bewitching cartoonist David B., and I’m told that the events with Philippe Claudel and Pascal Bruckner should be especially good.

I haven’t yet fulfulled the blogger’s imperative to stick in some cute French phrase, so …. Zut alors!

Tips of the Top Hat: New Yorker Eustace Tilley Contest Winners & Nerd Cakes

Emily Gordon writes:

Via our friends at UnBeige:

With his moncole at the ready and a butterfly his constant companion, Eustace Tilley has been The New Yorker‘s dapper mascot since founding art director Rea Irvin sketched him into being in 1925. The magazine recently invited readers to put their own twist on the discerning dandy in its fourth Eustace Tilley design contest. And this year’s competition came with a bookish bonus: the grand-prize winner’s design printed on a Strand Bookstore tote bag (an icon for an icon!) and a $1,000 Strand shopping spree. After sifting through roughly 600 entries, New Yorker art editor Françoise Mouly has selected a dozen winners, now featured in a slideshow on the magazine’s web site. The victorious Eustaces range from Seattle-based Dave Hoerlein‘s cartographic version (“A Dandy Map of New York”) to a Facebook-ready Tilley created by Nick McDowell of Mamaroneck, New York. Savannah-dwelling William Joca‘s “Cubist Tilley” was inspired by the work of Picasso (with a sprinkling of Ben-Day dots for good measure), while Pixo Hammer of Toronto channeled Joan Miro. As for the big winner, keep guessing (Grecian Eustace? Symbolic Eustace? Eustace through the years?). The champion and the tote bag will be revealed this spring.

My favorite of the examples UnBeige selected is by San Francisco illustrator and comic and storyboard artist Gary Amaro, whose other beautiful and emotionally charged work (including some remarkably fine nudes and figure drawings) you should look at here.

In other, or you could even say similar, passionate-niche news, I really like these nerd cakes.

Lewis and Glass: Parsing the Crooks and the Fools

Martin Schneider writes:

A rash assertion: Ira Glass and Michael Lewis are the two best people in the world at discussing the recent financial collapse in front of a lay audience.

Glass is host and producer of This American Life and works often with (and helped found) the “Planet Money” podcast. Lewis’s first book, Liar’s Poker, was about the bond market and Salomon Brothers, and his most recent bestseller, The Big Short, is about the dysfunctional real estate market of the George W. Bush years. These men have both spent countless hours figuring out just the right way to express to regular, informed non-experts what went so catastrophically wrong on Wall Street a few years back.

On February 3 they appeared together at 92Y.

The event was not boring. Actually, it was fairly riveting.

Glass was interviewing Lewis on this night, and he assumed the role of the people’s staunch advocate. He frequently expressed a desire to “get” those responsible for the crisis; Lewis was a bit more cagey about embracing that populism. This divide tells us, I think, a lot about the two men’s styles in general.

Glass is a middle-class constructive aspirer, and his work and personality reflect that in a more or less uncomplicated way. Lewis, for his part, may have hobnobbed with too many wealthy people in his life to be fully in sync with Glass on a number of issues, but it’s precisely that protean quality of his charm that may lie at the root of Lewis’s greatness as a reporter. Lewis worked as a bond salesman for several years, remember, and knows a lot more billionaires than the average muckraker. He’s not your typical left-wing slacker genius—but that slacker genius also could not have written Lewis’s books.

The dialogue at 92Y was primarily about two things, Lewis’s approach to reporting, and who was responsible for the financial collapse. Lewis was modest to a fault, calling himself “lazy” and indeed, elevating a certain kind of laziness as a key to his success: “I’m lazy…. I don’t want to spend time with people I don’t like.”

Glass quizzed Lewis about the problem of making a story like The Big Short readable. The formal problem of writing The Big Short is that the heroes of the book made billions of dollars on the collapse of the U.S. financial system, not normally a quality that endears a person to readers. (Lewis: “They bought fire insurance on your house and then watched it burn down.”) Glass asked if Lewis had “tricked” his readers into liking characters like Michael Burry and Steve Eisman, the two most memorable “shorters” in the book (Eisman was in the audience at 92Y). Lewis demurred: “Well, that’s the point—I really like them!”

Lewis addressed a dichotomy that comes up in the books, that of the difference between the “fools” and the “crooks.” In effect, per Lewis, the financial collapse was the result of a toxic combination of obliviousness and venality, and it’s not clear which of those is worse: “Wall Street can withstand the charge that they are behaving in societally unproductive ways. They can’t withstand the charge that they are actually stupid, bad with money.”

The longish session had too much to quote from, so I’ll stop now. It was a terrific event, and I was very happy to be in attendance. And also, I do recommend The Big Short (and This American Life too, duh).

Two Artworks on the Unfolding of Time

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Martin will be here with his weekly Wednesday events report, but I wanted to mention a couple of things myself.

Enough praise has been afforded to Christian Marclay’s 24-hour montage of time as a character in cinema, The Clock, at Paula Cooper Gallery. The lines were long this weekend. But it’s worth the wait: both exhilarating and magically relaxing. It suggests the wealth of human experience that has been represented on film, and even when the representation falls into repeated patterns, it only highlights the bristling variety of their expression. It ennobles every actor in every movie, no matter how bad, by turning them all into game walk-ons in a much greater project. (Update: As I left, I lamented that I was unlikely to see The Clock again anytime soon, once the show closes, and noted how odd that felt, given the ubiquity of video as a medium now. Felix Salmon has more on just this.)

Speaking of which, I was surprised how tremendously affecting I found John Adams’s Nixon in China at the Met—perhaps amplified by the inevitable resonance between the opera’s meditations on the ordinary makers of history, and events unfolding simultaneously in Egypt. As Nixon stammers early on, “News has a kind of mystery”—an immediate introduction to Alice Goodman’s way of working the mundane into the poetic. I had read about Pat Nixon’s intervention into Madame Mao’s play within a play—a ballet choreographed here by Mark Morris—but had no idea how it would unfold into a nightmare of history.

As for lickspittles so urgently concerned about the mocking treatment of Kissinger—if this is his worst fate, then that really is unjust.

Luxor, Egypt, 1996

Jonathan Taylor writes:

In other Egyptian news:

“With a budget of LE56 million, the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), in collaboration with Egypt’s Sound and Light organization and French lighting company Architecture Lumière, succeeded in installing 922 lighting units in different locations along the city’s west bank mountains, offering a new service to Luxor’s visitors, stated Culture Minister Farouk Hosni.”

At night, the darkness was total.

Fields of tall, deep-green cornstalks ended abruptly, forming a clean border with the desert. Behind you, the river was just out of sight, behind distant groves of palms. Far beyond this band of green was a creased swelling of mountain. Ahead of you here, too, on the west bank: another sand mountain, dazzlingly white in the sun, like a scrubbed bone. At its foot—nestled? cowering?—a village, whose lights glowed when the sun whent behind the hill, casting sudden shadow the shallow valley. Those lights, too, turned dark before too long.

You’re alone in a shabby, colorful hotel where the road that stretches from the river ends, right at the corn-desert border. You’re the only guest. Tired of answering questions about whether you’re married, and why not, you retire from the courtyard with the pool table, where men drink Stella—the Egyptian beer.

You emerge later at a safe hour. Ten P.M.? Midnight? The darkness is total, beyond the glare of a lone street lamp, so you go beyond the street lamp to where the darkness is total. The stars are emphatically present, yet not “bright,” they only confirm the darkness. The invisible cornstalks rustle maniacally in the wind as you walk down the road vanishing into the darkness ahead, to where the seated colossi rise on your left. Are they illuminated at night, like the great temples of the east bank? Or can you make them out dimly, knowing where they are from your daily journeys to and from the river. Don’t worry about it; in 15 years, you won’t remember anyway. You’ll be able to summon up either memory with equal convincing clarity.

This darkness, this silence harried by the whispery shrieks of the corn and the madcap howling of a disembodied jackal, this scrap of fertile soil in the shadow of a mass grave of kings and queens, this ocean of desert beyond, these thousands of years—who could fill it all, but gods reaching down from the sky?

Milton Rogovin and the Book Review that Shook Buffalo

Jonathan Taylor writes:

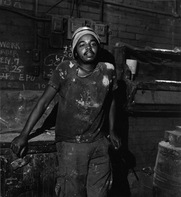

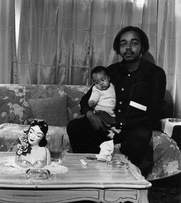

Milton Rogovin, aptly described on his website as “social documentary photographer,” died in January at age 101. A Buffalo optometrist, he was denounced as the city’s “Top Red” in 1957, and subsequently began photographing working people and the worlds that made them and that they made, in Buffalo and across the globe. For me, the series that stand out are Lower West Side Triptychs, photos of the same residents of that Buffalo neighborhood taken in 1972, 1984 and 1992, and Working People, described here by JoAnn Wypijewski, whose writings accompanied some of Rogovin’s publications:

From 1977 to 1980 Rogovin photographed Buffalo’s working people: two shots of each subject, one at work and one at home…. They are marvelously evocative pictures, chiefly because Rogovin asks his subjects to compose their own portraits. A steelworker may look saucy and conquering on the job; matronly and just a little anxious at home with her kids. An odd-job man may express nonchalance, even a touch of scorn, in the plant; while, seated before a tableau of religious icons, commercial calendars and his own “work” photo, a curious mix of defensiveness and melancholy. You can’t type these people, because each time you return to them, they may disclose a new story.

This passage appeared in a Nation review of Verlyn Klinkenborg’s The Last Fine Time, a portrait of Buffalo’s East Side through the windows of a local bar. Wypijewski, an East Side native, continues, “But Klinkenborg’s people are mute, and their silence accomplishes that other end of romanticism: the annulment of history.” It’s not just a monumental takedown, it’s a stunning throwdown over the turning of social history into “creative writing” for an audience of “the explaining classes.” (Fortunately, it’s online here.)

Wypijewski first dismantles the cliche of Buffalo’s snow: “From the first words of the prologue Klinkenborg disqualifies himself as Buffalo’s biographer. ‘Snow begins as a rumor in Buffalo, New York.’ Snow—the cheap association every amateur joker makes with Buffalo? Rumor—the hint of subterranean preoccupation? Nothing bores Buffalonians I know more than the ready equation of the city with snow-storms; and nothing is approached with more equanimity than those same snowstorms.” But her critique is much deeper:

The book is meant to be an homage to the soul of the old East Side. Klinkenborg catalogues its citizens by occupation, from dressmaker to steamfitter, foundryman to church keeper; and even by name, eight lines of lyrical consonant combinations, with a few Germans thrown in to break up the meter. But even in homage—in fact, because of it—the people are lost, the center becomes the periphery. As romanticist, Klinkenborg is the medium through which the working class can be seen, and the picture he draws—an emotional yet guarded people, brightly striving but always just a bit behind the eight ball of life—is stylized in a way coincident with accepted notions….

….Charitably, I would say that Klinkenborg wrote this book out of love for his father-in-law, and the same reason I was glad not to know the real views of my relatives who baited me about politics may have impelled Klinkenborg to walk only on the safe side of history’s street. The result, though, is that Eddie—and by extension Buffalo—serves simply as a prop for Klinkenborg’s writing, and once the bar is sold and Eddie moves out to the suburbs it is as if he has no meaning except in tragedy. Klinkenborg has got his story.

The review even led to a public debate at Erie Community College between Wypijewski, Klinkenborg and several others. (The Buffalo News reported that Klinkenborg “kept his composure throughout the evening and said it was all part of a learning process.”)

I haven’t even read The Last Fine Time, so I can’t even comment on Wypijewski’s fairness. But it’s undoubtledly an essay that only grows in stature as the book recedes into the past. It’s sad how hard it is to imagine a struggle over art and social history being waged so prominently today on the terrain Wypijewski staked out (though Noreen Malone’s warning against enthusiasm for photography of Detroit’s ruins is a faint echo—and one still richocheting among the explainers).

Even harder, of course, is to imagine what you see before your lyin’ eyes in many of Rogovin’s pictures: “a middle class that included blue collar workers who were able to support their families on a single income,” in the words of Roy Edroso, taking on another would-be representer of a fantasized working class—to whom Rogovin’s photos are an enduring rebuke.

Wypijewski remembers Rogovin both in The Nation and at Counterpunch. And Klinkenborg does, too, at the Times.

The Economist, the Director, the Neurologist, and the Playwright

Martin Schneider writes:

This week in events, we have a conversation, a lecture, and a play.

The Conversation. The Rubin Museum of Art in Chelsea, dedicated to the art of the Himalayas, hosted a weekly series called “Talks about Nothing”; it started last October. By a stroke of luck, I happened to catch the very last one (there were 26 events in all) this past Saturday evening. The series has attracted luminaries of all sorts to the sedate stage of the Rubin, and the one I happened to see featured Raj Patel, a young economist of renown, and Peter Sellars, a less young stage and opera director of renown. Patel has recently written a book called The Value of Nothing, which made him a perfect guest for this series.

Patel is young, sharp, and gentle, and speaks with a cultivated English accent. The theory presented in his book seems to be a jab against materialism and a celebration of the ineffable skills of nurturing, community organizing, household maintenance, and so forth, which Western economics generally valuates as “nothing.” The chat proceeded along such hyper-idealistic lines. In some ways it was a talk ideally suited to the Rubin, whose Buddhist calm (and evident money, somewhere) seems to attract well-meaning, educated, and affluent New Yorkers even more than 92Y does.

I think my favorite bit was when Patel said, “Taxation is a better way of redistributing wealth than letting some wealthy men on boats decide what they want to spend money on.” Amen to that. (The line drew applause.) I wish the talk had been a little more structured than it was—Sellars in particular is prone to meandering run-on sentences that do hit a lot of good points but are still, well, very long. However, it would be churlish to suggest that the discussion was not stimulating and intelligent. It was, and I wish I’d seen more of these “Talks about Nothing.” This was the first event at the Rubin I’ve ever seen, and I will be on the lookout for more.

The Lecture. On Tuesday night I had the pleasure of seeing V.S. Ramachandran at 92Y. It’s funny, I see a lot of illustrious people stand on stages and speak, but it’s rare that I see someone deliver an actual lecture. The one that Ramachandran delivered was top-notch. Ramachandran has become renowned for a kind of investigative neurology—the most mentioned example is his work on phantom limbs—wherein he exploits a given patient’s lesion-induced lack of a specific ability—for example, a patient’s inability to recognize his own mother—to wheedle out truths about the human brain and the evolution that created it.

Ramachandran spoke in the unfussy patter of the scientist, intermittently sprinkled with witty and caustic asides on his unimaginative colleagues (or critics). In addition to a brief bit on the already well publicized phantom limbs story, Ramachandran spoke vividly about the potentially immense importance of “mirror neurons,” recently discovered to exist in the brain. Mirror neurons allow humans (and other primates) to analogize from the actions of other creatures, and this wondrous mental gift may have allowed humans to adapt at a rate faster than the glacial speed of Darwinian evolution. He also spoke evocatively about the importance of synesthesia in allowing us to understand the importance of metaphor to human thought. Stirring, ambitious stuff!

All in all, I had the impression, watching Ramachandran, that I was watching an unusually exceptional person. I’m grateful for 92Y for presenting him to the audiences of New York (although, as he has a new book to sell, he won’t be hard to find).

The Play. On Thursday I went to Playwright Horizons on 42nd Street to see A Small Fire, by Adam Bock. The run of the play is now over, alas—it was an intuitive gem. A specific thing happens to one of the characters over the course of the play, which I won’t reveal, but A Small Fire is about the way family and friends adjust to new frailty in one among them. Not everyone reacts well, but some do.

Bock makes some unusual decisions, but for me they all paid off handsomely. One example was a speech towards the end that was threatening to become mawkish—at that precise moment the character, distracted by the all-important arrival of his racing pigeon, starts shouting and pointing and thus the scene ends. Canny self-awareness there on the part of Bock. Furthermore, the nuances and speech patterns of people who know each other very well are excellently captured, and the emotional payoff at play’s end—nearly wordless—is superficially shocking but entirely apt and earned. Bravo.

That’s all for this week. Be sure and see some events of your own! You know I’ll do my part.