-thumb-400x535.jpg)

Education for the Real World:

Look carefully at the map of the “city” (traversed by “I-494”) in this subway ad.

–Jonathan Taylor

Author Archives: Jonathan

“Some Woman Book-Maker Named, I Believe, Toni Morrison?”

Jonathan Taylor writes:

In a de facto way, I don’t post links to great Awl posts, because how would I choose, where would I stop? But I must pay tribute to this monument of literary parody: Selections From V.S. Naipaul’s Yelp Account, by Mike Barthel.

Beyond the Iron Gates: A Third Volume of Fermor’s Walk

Jonathan Taylor writes:

A tidbit of something to look forward to, in the Guardian‘s article on the death of Patrick Leigh Fermor at age 96. Fermor in 1977 and 1986 published two volumes recounting a 1933-34 journey from Holland to Constantinople on foot: A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water, which ended at the Iron Gates of the Danube, between Serbia and Romania.

Readers are still awaiting the promised third leg of Leigh Fermor’s trip, despite the author’s repeated promises to “pull my socks up and get on with it” and his 2007 declaration that he was learning to type so that he could complete it more quickly.

Cooper, who visited him at his Greek home earlier this year, said that the writer had been working on corrections to a finished text. “A early draft of the third volume has existed for some time, and will be published in due course,” she said.

Some Highbrow Literary Profiles from People Magazine in the 1970s and 80s

An Angry Black Poet of the 1960’s, Nikki Giovanni Cools Down with Success By Patricia Burstein, July 12, 1976

Writers Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne Play It as It Lays in Malibu By John Riley, July 26, 1976

Author Susan Sontag Rallies from Dread Illness to Enjoy Her First Commercial Triumph By Barbara Rowes, March 20, 1978

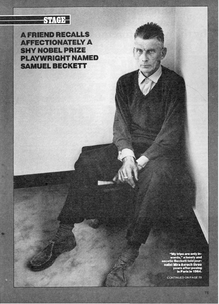

A Friend Recalls Affectionately a Shy Nobel Prize Playwright Named Samuel Beckett By Mira Avrech, April 13, 1981

Nobel Prize Winner Isaac Bashevis Singer on Life, Sex and the Storyteller’s Art By Allan Ripp, May 17, 1982

Nadine Gordimer: A Radical South African Novelist Writes Paeans to Revolutionaries and Awaits a Racial Apocalypse By Joshua Hammer, March 26, 1984

After 31 Years, Don Bachardy and Christopher Isherwood Are Still a Portrait of Devotion By Carol Wallace, May 21, 1984

Saul Bellow Returns to Canada, Searching for the Phantoms That Shaped His Life and Art By Joshua Hammer, June 25, 1984

Also, music and art:

Francis Bacon: a Great English Painter Brings His Horror Show to America By Lee Wohlfert, April 21, 1975

Painter Alice Neel Strips Her Subjects to the Bone—and Some Then Rage in Their Nakedness By Patricia Burstein, March 19, 1979

Philip Glass Composes a Sanskrit Opera About Gandhi, but Who Can Understand a Word of It? By Joseph Roddy, October 06, 1980

—Jonathan Taylor

When Janet Malcolm Broke the New Yorker’s Profanity Barrier

Jonathan Taylor writes:

[Update: Back Issues locates an even earlier use of the word “asshole” in The New Yorker, in 1975, among other corrections to Green’s list.]

Bookforum corrects the assertion by Elon Green in The Awl that the word “asshole” was first used in The New Yorker in 1994 (as you would gather from the mag’s own site search). In fact, the word “assholes” is believed to have debuted in a quote in an October 20-27, 1986, two-part Profile by everyone’s favorite antijournalist, Janet Malcolm, “A Girl of the Zeitgeist.”

The “Girl” in question was Ingrid Sischy, editor of Artforum. This portrait of the “art world” through Sischy–herself a curiously fleeting presence in her own profile–drew a response (also two-part) by the Village Voice‘s art critic at the time, Gary Indiana, subtitled “Breaking the Asshole Barrier.” He wrote, “The maiden appearance of the word ‘asshole’ is the least distressing infelicity in Malcolm’s article, but in the context of The New Yorker it seems portentous of the shape of things to come.”

In part one, Indiana dissected what he calls Malcolm’s “trial-by-interior,” in which she communicated her estimates of her interlocutors through her admiration, or lack thereof, of their domestic spaces: Rosalind Krauss, utterer of the word “assholes,” lives in “one of the most beautiful living places in New York.”

Artists themselves, Indiana said, didn’t come off so well in Malcolm’s method: Sherry Levine told him, “I knew nothing good was coming when the fact checker from The New Yorker called to ask me if it would be accurate to say that my bathtub is in the kitchen and I live alone with my cat,” and asked Levine to define “railroad apartment.”

(Malcolm also somewhat famously critiqued Sischy’s style of chopping tomatoes: “She took a small paring knife and, in the most inefficient manner imaginable, with agonizing slowness, proceeded to fill a bowl, tiny piece by tiny piece, with chopped tomatoes. Obviously, no one had ever taught her the technique of chopping vegetables, but this had in no way deterred her from doing it in whatever way she could or prevented her from arriving at her goal.”)

The other “famous story” about profanity in The New Yorker, of course, is Norman Mailer declaring that “true liberty” meant the “right to say shit in The New Yorker.”

Kurt Andersen’s “Words We Don’t Say,” Circa 1997

Jonathan Taylor writes:

A quaintly short list! An Emdashes tradition.

Obligatory Rapture (Re)Post

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Have You Seen the Pearl? Tolkin’s ‘Rapture’ Gets Its Due

I’ll Stick With “Foodie”?

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Bon appetit, techies!

UnderWikied? An Occasional Series

Jonathan Taylor writes:

In this age of the gloriously elaborated Wikipedia page, I’ve lately come across a number of entries that I’m surprised are so scanty. I am going to start taking note of some of them here.

Today’s entry: Jane Bowles.

A Study in the Contingency of Journalism: Arendt’s ‘Eichmann’ Typescript at Tablet

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Tablet has some fascinating samples of the typescript of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, marked up with New Yorker editor William Shawn’s editing changes. Allison Hoffman explains, “the text that most people have in mind when they talk about Arendt’s report is not, in fact, the one that appeared in the magazine.” Shawn’s

major cuts and alterations to Arendt’s original are striking in their consistency: Almost all of them involve Arendt’s asides about the contemporary Jewish community and its handling of the trial. Many of the most controversial passages made it into the magazine intact, including her assertion that “if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between five and six million people.” But the final magazine text is in some ways less provocative, more streamlined, and–unsurprisingly, given the precision of The New Yorker‘s legendary copy editor Eleanor Gould–more polished than what’s in the book.

Above all, the manuscript pages, and Hoffman’s backgrounder, give a great sense of the contingency of these things. As Hoffman notes, Arendt wrote her report for The New Yorker because Commentary couldn’t afford to send her to the trial, and “one can only imagine that the final product would have been quite different had Arendt been writing for” Norman Podhoretz.