Jonathan Taylor writes:

Tomorrow night at 6:30, Dale Peck and Rick Moody share the stage in a post-grudge match, to discuss Thomas Bernhard’s My Prizes, at the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York City. (Free, but reservation is required.)

Here is Peck’s pretty wonderful Christmas Eve review of My Prizes from the cover of the Times Book Review. I thought it was devilishly perverse that the real payoff—Peck’s explanation of the significance of the texts Bernhard’s prize acceptance speeches themselves—comes only at the end of a relatively long essay that, I imagine, your median Sunday reader may not have gotten as far as.

A more dismissive take on these speeches can be found in Zadie Smith’s review in the March Harper’s, but for registered subscribers only.

Author Archives: Jonathan

A Drinking Game for Any Cocktail Party: When Anyone Says ‘Apparently’

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Someone’s probably written about this already, but, my sometimes ingenious search skills haven’t managed to draw it out.

Tyler Cowen linked to a post by James Somers from about a year ago, about the skillful deployment of the phrase “It turns out….” He says it can have the magical effect of convincing even alert readers, in the absence of evidence, of a proposal “in large part because they come to associate it with that feeling of the author’s own dispassionate surprise.”

This reminded me of an observation—not exactly related and not nearly so incisive—that I’ve long made about the use of the word “apparently,” by people relating information recently gleaned from the news: “Apparently, GE not only paid no taxes last year, the Treasury actually owed it billions of dollars.” (See Felix Salmon for a great overview on the follow-up to that Times story.)

In fact, this usage is touched on in Google’s dictionary definition: “Used by speakers or writers to avoid committing themselves to the truth of what they are saying.” It’s my guess that people use this particularly often in relation to things they read in the New York Times, because it does require some implicit acceptance of the authority of the source. I think even the same people might not say the same thing about something they heard on NPR, but would more likely say, “I heard on NPR that….” Hearing a voice telling you on the radio maybe makes it too clear that the information is second-hand to you, whereas the disembodied authority of one’s most trusted written word is more easily assimilated to one’s own “knowlege.”

However, “apparently” also suggests an openness to acquiring completely new information; I doubt devotees of the Wall Street Journal editorial page introduce their games of telephone with any such qualifier; after all, that information is previously held and immutable belief, not new data.

In any case, use of apparently, overall, is apparently on the decline. If my theory is correct, perhaps the Times paywall will erode it even further.

‘The World’s Largest Interior Visual Design Medium’

![]()

_Jonathan Taylor writes:_

“Via”:http://andrewsullivan.theatlantic.com/the_daily_dish/2011/04/ode-to-airport-carpets.html Andrew Sullivan, an appreciation of “airport carpets”:http://www.iconeye.com/index.php?view=article&catid=1:latest-news&layout=news&id=4576:crimes-against-design-airport-carpets&option=com_content&Itemid=18, from George Pendle at IconEye.

What Is the Best Book About Cokie Roberts?

Jonathan Taylor writes:

An intriguing tip for choosing books to read, from Tyler Cowen:

5. The very best books in categories you think you cannot stand (“gardening,” “basketball,” whatever) will be superb. It is not hard to find out what they are.

Have You Seen the Pearl? Tolkin’s ‘Rapture’ Gets Its Due

Jonathan Taylor writes:

I normally avoid the cross fire of film criticism, but must quickly second Wolcott’s estimation of the “stupendous” post at The Sheila Variations about Michael Tolkin’s 1991 film The Rapture, illustrated with a stunning parade of the faces of Mimi Rogers; as many times as I’ve seen this film, I was too often too focused on what Tolkin was up to, to realize how much Rogers was doing.

I’d even quibble with Sheila’s assessment of the girl who plays Rogers’s daughter—or at least of the hair-raising effect of her whiny plea, “Why can’t we die now, mommy?” (Just see it. Ditto re: “the pearl.”)

I think Gary Indiana somewhere described Tolkin’s films as “period movies about the present.” That present still remains ours enough to still feel this effect, even as it is now enough the past, to add another layer of significance.

There Are Delicious Sensations: The Paris Review Celebrates Sybille Bedford

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Last Thursday, the Paris Review hosted a convivial reading from the works of novelist, memoirist and journalist—of author—Sybille Bedford, who would have turned 100 this year (and came closer than most; an Alan Hollinghurst article headlines her as a “Child of the Century“). The event was organized by Lisa Cohen, the author of the forthcoming All We Know—”portraits of the neglected modernist figures Esther Murphy, Mercedes de Acosta, and Madge Garland”—and a friend of Bedford.

Cohen called Bedford a “sympathetic, vulnerable mind,” exhibiting something of the gift for “compression” she also noted in Bedford’s writing. To wit: Courtney Hodell read from the opening of Bedford’s travelogue of Mexico, A Visit to Don Otavio, which includes the observation that “Arrival and Departure are the two great pivots of American social intercourse…. What counts is that you are new. In Europe where human relations like clothes are supposed to last, one’s got to be wearable.”

And in an assessment of her protagonist’s first sexual encounter with a man, in the novel Jigsaw, Bedford wrote, and novelist Sylvia Brownrigg read, “There were no delicious sensations.”

Poet and memoirist Honor Moore read climactically from the opening of Bedford’s last book, Quicksands, in which Bedford plunges back through the decades to resurrect that vulnerability in her formation as a writer.

These were all passages I knew, but a dramatic reading of Bedford’s account of the British Lady Chatterley’s Lover obscenity trial, by Cohen and Caleb Crain, revealed to me for the first time the felicitous role of Richard Hoggart, the British pioneer of cultural studies and author of the wondrous The Uses of Literacy in 1957. (I also just learned that Hoggart assembled the words “Death-Cab for Cutie”—as a made-up title for a type of “sex and violence novel,” as part of The Uses of Literacy‘s study of the encroachment of mass popular culture on traditional working-class culture.)

Born in 1918, Hoggart is not much younger than Bedford would have been (yes, is—still alive!). He argued that Lawrence’s novel was essentially “puritanical” in its sense of exceedingly stringent responsibility to conscience. Bedford recorded prosecutors’ smug attempts to mock his hypothesis by reading him passages laden with four-letter words (or five, in the pertinent case of “balls”). As played by Cohen, he responded as an enthusiastic teacher might to eager students thirstily requesting further demonstrations of his wisdom.

The reading had a little bit of a feel of a private party, a slumber party in Lorin Stein’s rec room. It was not inappropriate to the esprit of the friends you might find gathered, in her books, in a Provence farmhouse; nor to the consequent sense of being in good company one feels privy to, once you’ve started reading Bedford. I read her books at the same time as I did a number of her contemporary authors of travel and discovery, like Lawrence Durrell and Patrick Leigh Fermor. More than theirs do Bedford’s books crackle with the formation of thought amid the unpredictable eventfulness of company.

Thus it was a bit disappointing that the podium was limited strictly to readings, with no further discussion or reminiscence, what with Cohen in the house, as well as (if I understood correctly) Bedford’s friend and literary executor, Aliette Martin. Fortunately, the Paris Review‘s site promises to post a series of “essays and archival finds” on Bedford, beginning with this post by Cohen, this by Brenda Wineapple, and a 1963 Review interview.

Two Artworks on the Unfolding of Time

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Martin will be here with his weekly Wednesday events report, but I wanted to mention a couple of things myself.

Enough praise has been afforded to Christian Marclay’s 24-hour montage of time as a character in cinema, The Clock, at Paula Cooper Gallery. The lines were long this weekend. But it’s worth the wait: both exhilarating and magically relaxing. It suggests the wealth of human experience that has been represented on film, and even when the representation falls into repeated patterns, it only highlights the bristling variety of their expression. It ennobles every actor in every movie, no matter how bad, by turning them all into game walk-ons in a much greater project. (Update: As I left, I lamented that I was unlikely to see The Clock again anytime soon, once the show closes, and noted how odd that felt, given the ubiquity of video as a medium now. Felix Salmon has more on just this.)

Speaking of which, I was surprised how tremendously affecting I found John Adams’s Nixon in China at the Met—perhaps amplified by the inevitable resonance between the opera’s meditations on the ordinary makers of history, and events unfolding simultaneously in Egypt. As Nixon stammers early on, “News has a kind of mystery”—an immediate introduction to Alice Goodman’s way of working the mundane into the poetic. I had read about Pat Nixon’s intervention into Madame Mao’s play within a play—a ballet choreographed here by Mark Morris—but had no idea how it would unfold into a nightmare of history.

As for lickspittles so urgently concerned about the mocking treatment of Kissinger—if this is his worst fate, then that really is unjust.

Luxor, Egypt, 1996

Jonathan Taylor writes:

In other Egyptian news:

“With a budget of LE56 million, the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), in collaboration with Egypt’s Sound and Light organization and French lighting company Architecture Lumière, succeeded in installing 922 lighting units in different locations along the city’s west bank mountains, offering a new service to Luxor’s visitors, stated Culture Minister Farouk Hosni.”

At night, the darkness was total.

Fields of tall, deep-green cornstalks ended abruptly, forming a clean border with the desert. Behind you, the river was just out of sight, behind distant groves of palms. Far beyond this band of green was a creased swelling of mountain. Ahead of you here, too, on the west bank: another sand mountain, dazzlingly white in the sun, like a scrubbed bone. At its foot—nestled? cowering?—a village, whose lights glowed when the sun whent behind the hill, casting sudden shadow the shallow valley. Those lights, too, turned dark before too long.

You’re alone in a shabby, colorful hotel where the road that stretches from the river ends, right at the corn-desert border. You’re the only guest. Tired of answering questions about whether you’re married, and why not, you retire from the courtyard with the pool table, where men drink Stella—the Egyptian beer.

You emerge later at a safe hour. Ten P.M.? Midnight? The darkness is total, beyond the glare of a lone street lamp, so you go beyond the street lamp to where the darkness is total. The stars are emphatically present, yet not “bright,” they only confirm the darkness. The invisible cornstalks rustle maniacally in the wind as you walk down the road vanishing into the darkness ahead, to where the seated colossi rise on your left. Are they illuminated at night, like the great temples of the east bank? Or can you make them out dimly, knowing where they are from your daily journeys to and from the river. Don’t worry about it; in 15 years, you won’t remember anyway. You’ll be able to summon up either memory with equal convincing clarity.

This darkness, this silence harried by the whispery shrieks of the corn and the madcap howling of a disembodied jackal, this scrap of fertile soil in the shadow of a mass grave of kings and queens, this ocean of desert beyond, these thousands of years—who could fill it all, but gods reaching down from the sky?

Milton Rogovin and the Book Review that Shook Buffalo

Jonathan Taylor writes:

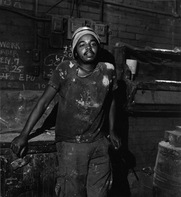

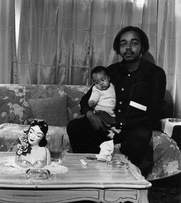

Milton Rogovin, aptly described on his website as “social documentary photographer,” died in January at age 101. A Buffalo optometrist, he was denounced as the city’s “Top Red” in 1957, and subsequently began photographing working people and the worlds that made them and that they made, in Buffalo and across the globe. For me, the series that stand out are Lower West Side Triptychs, photos of the same residents of that Buffalo neighborhood taken in 1972, 1984 and 1992, and Working People, described here by JoAnn Wypijewski, whose writings accompanied some of Rogovin’s publications:

From 1977 to 1980 Rogovin photographed Buffalo’s working people: two shots of each subject, one at work and one at home…. They are marvelously evocative pictures, chiefly because Rogovin asks his subjects to compose their own portraits. A steelworker may look saucy and conquering on the job; matronly and just a little anxious at home with her kids. An odd-job man may express nonchalance, even a touch of scorn, in the plant; while, seated before a tableau of religious icons, commercial calendars and his own “work” photo, a curious mix of defensiveness and melancholy. You can’t type these people, because each time you return to them, they may disclose a new story.

This passage appeared in a Nation review of Verlyn Klinkenborg’s The Last Fine Time, a portrait of Buffalo’s East Side through the windows of a local bar. Wypijewski, an East Side native, continues, “But Klinkenborg’s people are mute, and their silence accomplishes that other end of romanticism: the annulment of history.” It’s not just a monumental takedown, it’s a stunning throwdown over the turning of social history into “creative writing” for an audience of “the explaining classes.” (Fortunately, it’s online here.)

Wypijewski first dismantles the cliche of Buffalo’s snow: “From the first words of the prologue Klinkenborg disqualifies himself as Buffalo’s biographer. ‘Snow begins as a rumor in Buffalo, New York.’ Snow—the cheap association every amateur joker makes with Buffalo? Rumor—the hint of subterranean preoccupation? Nothing bores Buffalonians I know more than the ready equation of the city with snow-storms; and nothing is approached with more equanimity than those same snowstorms.” But her critique is much deeper:

The book is meant to be an homage to the soul of the old East Side. Klinkenborg catalogues its citizens by occupation, from dressmaker to steamfitter, foundryman to church keeper; and even by name, eight lines of lyrical consonant combinations, with a few Germans thrown in to break up the meter. But even in homage—in fact, because of it—the people are lost, the center becomes the periphery. As romanticist, Klinkenborg is the medium through which the working class can be seen, and the picture he draws—an emotional yet guarded people, brightly striving but always just a bit behind the eight ball of life—is stylized in a way coincident with accepted notions….

….Charitably, I would say that Klinkenborg wrote this book out of love for his father-in-law, and the same reason I was glad not to know the real views of my relatives who baited me about politics may have impelled Klinkenborg to walk only on the safe side of history’s street. The result, though, is that Eddie—and by extension Buffalo—serves simply as a prop for Klinkenborg’s writing, and once the bar is sold and Eddie moves out to the suburbs it is as if he has no meaning except in tragedy. Klinkenborg has got his story.

The review even led to a public debate at Erie Community College between Wypijewski, Klinkenborg and several others. (The Buffalo News reported that Klinkenborg “kept his composure throughout the evening and said it was all part of a learning process.”)

I haven’t even read The Last Fine Time, so I can’t even comment on Wypijewski’s fairness. But it’s undoubtledly an essay that only grows in stature as the book recedes into the past. It’s sad how hard it is to imagine a struggle over art and social history being waged so prominently today on the terrain Wypijewski staked out (though Noreen Malone’s warning against enthusiasm for photography of Detroit’s ruins is a faint echo—and one still richocheting among the explainers).

Even harder, of course, is to imagine what you see before your lyin’ eyes in many of Rogovin’s pictures: “a middle class that included blue collar workers who were able to support their families on a single income,” in the words of Roy Edroso, taking on another would-be representer of a fantasized working class—to whom Rogovin’s photos are an enduring rebuke.

Wypijewski remembers Rogovin both in The Nation and at Counterpunch. And Klinkenborg does, too, at the Times.

Good Riddance to Summer’s Tomatoes

Jonathan Taylor writes:

At the markets here in New York, there are still plenty of tomatoes to be had, but you can tell the season is on the wane. Thank God. I am tired of summer’s tyranny of ingredients over the cooking process, of avoiding actual cooking due to the stifling weather—and simply tired of all the tomatoes, however delicious for eating raw or cooked into a simple pasta sauce.

It is time, in autumn, to reacquaint ourselves with the civilizing process. A tomato dish that I made both Saturday and Sunday is the way to bid a fond but firm farewell to the tomato, and submit nature to the genius of cookery. In other words, the tomatoes are cooked with cream. It is also a recipe whose modest nature and brusque expression are foreign to the didacticism and the sentimental mugging found in so much food writing these days.

First, the recipe, and then some notes on its source:

Tomates à la crème

Take six tomatoes. Cut them in halves. In your frying pan melt a lump of butter. Put in the tomatoes, cut side downward, with a sharply pointed knife puncturing here and there the rounded sides of the tomatoes. Let them heat for five minutes. Turn them over. Sprinkle them with salt. Cook them for another 10 minutes. Turn them again. The juices run out and spread into the pan. Once more turn the tomatoes cut side upward. Around them put 80 grams (3 ounces near enough) of thick cream. Mix it with the juices. As soon as it bubbles, slip the tomatoes and all their sauces onto a hot dish. Serve instantly, very hot.

In 1967, Elizabeth David wrote an article about French cookbook author Edouard de Pomiane for the London Sunday Times that was also published in Gourmet in March 1970 (perhaps it can be found in the new Gourmet iPad app?), and in David’s 1984 collection An Omelette and a Glass of Wine. It includes those verbatim instructions of Pomiane’s for tomates à la crème.

As David notes of the dinner menu that Pomiane presented tomates à la crème as a part of, it is “a real lesson in how to avoid the obvious without being freakish” and “how to start with the stimulus of a hot vegetable dish.” Even once I had just read the recipe, it was easy to picture as a canonical bistro classic. But that was not the case; David wrote that it “makes tomatoes so startingly unlike any other dish of cooked tomatoes that any restaurateur who put it on his menu would, in all probability, soon find it listed in the guide books as a regional speciality.” But the Pomiane attributed the dish to his Polish mother, and David notes that many of his techniques are actually traceable to Central European cooking—”thereby refreshing French cookery in the perfectly traditional way.”

David was also out to praise Pomiane’s way of food writing: “courageous, courteous, adult. It is creative in the true sense of that ill-used word, creative because it invites the reader to use his own critical and inventive faculties.” Like her own writing it, it resists promiscuous superlatives, emotional self-indulgence and much cant surrounding authenticity: “He passes speedily from the absurdities of haute cuisine to the shortcomings of folk cookery, and deals a swift right and left to those writers whose reverent genuflections before the glory and wonder of every least piece of cookery-lore make much journalistic cookery writing so tedious.”

A more practical virtue of the tomates recipe is that it will come in handy even when you’re not up to your ears in Greenmarket heirloom tomatoes. Those will certainly make the dish better, but it is also a recipe that can make something much more presentable out of inferior supermarket tomatoes. Take Julian Barnes’s word for it:

I didn’t much trust this: the quantity of butter was imprecise, the strength of the gas unspecified. Further, it was mid-February, so the best tomatoes I could find were pale orange, frost-hard, and pretty juice-free inside. I fanatically observed the approximations of De Pomiane’s recipe, while chucking in a little salt, pepper and sugar in the tiny hope of not disgracing the kitchen … and the result was unbelievably good – the method had somehow extracted richness from half a dozen fruits that looked as if they had long ago mislaid their essence.