Jonathan Taylor writes:

Tonight in New York City at 8:00, 92 Street Y hosts Lydia Davis for “An Evening of Madame Bovary.”

Kathryn Harrison’s Times review of Davis’s new translation of Madame Bovary makes a great case for (re)reading the novel, but doesn’t really flesh out why Harrison finds Davis’s translation choices so convincing. “Faithful to the style of the original, but not to the point of slavishness, Davis’s effort is transparent,” she writes, but that only raises questions of the sort the translator herself will probably address tonight.

Davis is not only a translator of Flaubert, but a fellow novelist (something often overlooked in the attention to her distinctive short fiction), who, within her essential novel The End of the Story, writes about the process of constructing a novel with the something like the meticulousness of Flaubert’s that Harrison describes. A good recent interview by the Rumpus does justice to The End of the Story.

Author Archives: Jonathan

Tonight, on the High Line, Free: Remedial NYC Food History

Jonathan Taylor writes:

As much as the High Line is everybody’s favorite example of well-designed adaptive reuse of abandoned industrial infrastructure, it’s amazing that, in an age of endless food jabber, the story of the High Line’s role in feeding New York is not more talked-about. Perhaps it’s because it belongs to the golden age of food industrialization, and goes against the grain of a preferred “artisanal” gastronomic past. (Click on image to see Father Knickerbocker devouring rail cars in 1938.)

But as food historian Rachel Laudan explains in a wonderful article, projecting such reigning preferences onto the past distorts it. And a free talk to be given on the High Line tonight by Patrick Ciccone should shed some needed light onto the scale and complexity of the food systems that it has taken to sustain a major metropolis, not just one’s own kitchen table.

It’s tonight at 6:30, in the Chelsea Market Passage section of the High Line, between 15th and 16th Sts.

“And That Is Just What I Meant”: A Last Jab from Tony Judt

Jonathan Taylor writes:

If this reply to a self-parodic letter writer in the New York Review of Books turns out to be the last thing Tony Judt wrote, it would be fitting farewell to a debased world.

Hysteria, Histrionics, Hypocrisy: The Theater of Thomas Bernhard Comes to New York City

Jonathan Taylor writes:

I’ve traveled to Thomas Bernhard’s house and met his half-brother, and organized a reading and a panel discussion on him. But I, like most readers of Bernhard on this side of the Atlantic, have never seen any of his plays performed. However, in his native Austria, Bernhard’s status derived at least as much from his theatrical work (and behavior) as it did on his novels and other prose. As a young man, he himself trained as an actor, and his assaults on the Austrian state and cultural overclass were primarily acted out, as it were, on the stage, culminating in the 1988 furor over his “Heldenplatz” at Vienna’s Burgtheater.

I’ll be seeing my first Bernhard play in a couple weeks, when the Toronto-based One Little Goat theater company, directed by Adam Seelig, brings its production of Bernhard’s 1986 play “Ritter, Dene, Voss,” to New York’s La MaMa E.T.C., from September 23 to October 10 (tickets here). I spoke with Seelig recently about “Ritter, Dene, Voss,” and how this play’s metatheatrical twist is the perfect vehicle for One Little Goat’s mission of developing what it calls a “poetic theater.”

The play is set in the Viennese mansion where the two Worringer sisters, wealthy dilettante actresses, live, and where they have brought home their brother Ludwig from the Steinhof mental hospital. The title of the play is composed of the names of the prominent German actors who are specified in the text as the players of the three roles: Ilse Ritter, Kirsten Dene and Gert Voss.

The character Ludwig is, not for the first time in Bernhard’s oeuvre, loosely based on characteristics of Ludwig Wittgenstein and his brother Paul. It’s a bit as if, say, Harold Pinter had written a play called, I don’t know, “Gielgud, Ashcroft, Redgrave,” with Gielgud playing the part of, who—Bertrand Russell maybe?

The One Little Goat production, which has been seen in Toronto and Chicago, does not star Ritter, Dene, or Voss, and avoids any futile attempt to incorporate or transmit the associations they would carry to Austrians. (Seelig notes that he has avoided seeing any rendition of the original production, directed by Bernhard’s frequent collaborator, Claus Peymann.) The La MaMa production stars Maev Beaty, Shannon Perreault and Jordan Pettle, and Seelig says he would willingly retitle the play in his production after them, if it were permitted.

JT: How did you first become aware of Bernhard and “Ritter, Dene, Voss”?

AS: I knew Bernhard the way you and so many others know Bernhard, as a novelist. I was familiar with some of the novels, I admired the writing, [and learned that] he was equally a playwright, that he virtually alternated between novels and plays. And as someone who directs plays, I started to examine them. What caught my attention immediately is the unpunctuated text, and the lack of, or at least the sparse, stage directions. In other words, this is a perfect fit for the kind of work I’m developing with One Little Goat, which we’re calling poetic theater. And what that means is, text that can be treated as a score, highly interpretive plays—plays that actors can seriously dig into and make choices, while still holding on to the possibility for multiple interpretation, and the ambiguity that poetry is capable of, and theater so often is not.

JT: Does your poetic theater approach depend on producing plays that lend themselves to it in the way they are written, or can it be a way of approaching just any old play?

AS: That’s a good question. The honest answer is, I don’t know. A better effort at the answer is that, to begin with, it’s wonderful to work with texts where the writer places a great deal of trust in the performers…. This is the perfect play for it, right? As you know, from the note Bernhard wrote [at the end of the play]: “Ritter, Dene, Voss intelligent actors.” So this is a play that writes up to the actors, as it were, as opposed to one that traps them in a kind of hard mask. If you will, the mask here is a soft mask.

And I think it would be a bit of a battle to take one of those, any old play as you say, and try to tone down the character in order for the actor to come through a little more. It would be more of a challenge, although, hey, it would be fantastic to try that.

JT: That’s interesting what you say about the respect for the actor, because there’s also a way that it struck me that Bernhard, by naming the actors, is kind of singling them out and toying with them. It certainly highlights the relationship of the author to the actors and the characters, alongside that between the actors and the characters.

AS: On the one hand, it’s extraordinarily respectful of the actors….he’s giving them a great deal of freedom. On the other hand, I think he is deliberately challenging them to negotiate an extraordinarily challenging text. It has, believe me, we’re finding a great deal of pleasure doing it, but yes, there are moments when you say, “Fuck you, Thomas Bernhard! You’ve deliberately made that hard on us.” And that is a form of—it’s not just a hagiography of the actors, it’s a form of tough love, and it hurts some times.

The whole premise of the play is a deliberate challenge. On the one hand, this play is seriously “entertaining.” This is the thing that Bernhard really understood. He uses it pejoratively in the play, but the phrase “world of entertainment” comes out; he understood that this is a world of entertainment, and so the play, he writes it with some very high stakes. In that sense it’s really Drama 101: What’s going to happen? There is suspense in terms of what’s going to happen, how is the brother, if at all, going to be reintegrated into the family, and what’s that going to cause? So you have the standard, someone-is-going-to-come plot scenario. You have the status quo, the two sisters live together, and the brother comes in and upsets it…. But in Bernhard’s case it’s also anti-theater, because there’s a reference in the play to this maybe being the 18th or 19th time that they’ve tried to do this!

JT: Are there particular junctures of the play that illustrate how you carry out your approach in this particular production?

AS: There are a few key moments, that I don’t want to reveal, to be honest. But generally speaking, it’s not so much a matter of our method. It’s much more a matter of casting. If you switch out one actor in this play, it will be an entirely different play. And that’s the kind of play that this is. Even if these actors tried to put up the most farcical of masks, the hardest of masks, the most ironclad of characters as it were, it would still be a totally different play every time you change the actors. So it’s a much more global thing, it’s not like, moment to moment we have a certain method…. And so I do want to turn attention to these actors, I mean I have three phenomenal actors, whose play it is—it’s their play.

That may not be such huge news, but I think a lot of people have been treating theater as if the play is distinct from the people who perform it. And I think that Bernhard is really clearly calling our attention to it by naming the actors for whom he wrote.

JT: You’ve written that this play’s “central subject, ultimately, is the art of acting. The two Worringer sisters, after all, are actresses, making Bernhard’s play a meta-play that simultaneously shows and addresses the machinations of theatremaking.” Can you tell me a little more about how Bernhard treats the theater as his subject?

AS: With Bernhard, one of the biggest words across the board, in both novels and plays, is “hypocrisy,” and theater is—and I mean this in the most loving way—a hypocritical art form. Every fiction that we create has its share of hypocrisy, because we are taking sincere feelings, sincere emotions, sincere actions, between each other on stage, and we’re manipulating them and tweaking them for dramatic purposes. So we’re taking our truth, an we’re messing with it. So I think that Bernhard, he understands how performers operate, how the theater operates, so brilliantly, so clearly, that he calls out that very hypocrisy, and that kind of covenant that’s sealed between the actors and the audience—that we all buy into the fiction.

American Psycho or NYT? (No, Not Thomas Friedman)

Jonathan Taylor writes:

In the tradition of “Lesbian or German Lady?” comes “American Psycho or New York Times?” For example:

“Standing at the island in the kitchen I eat kiwifruit and a slice Japanese apple-pear (they cost four dollars each at Gristede’s) out of aluminum storage boxes that were designed in West Germany. I take a bran muffin, a decaffeinated herbal tea bag and a box of oat-bran cereal from one of the large glass-front cabinets that make up most of an entire wall in the kitchen.”

Punctuation Papers: Newton’s Pound Sign and the Fullest Stop

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Those awaiting the results of the punctuation letter-writing contest should take a look in the meantime at some smooth quillwork by Sir Isaac Newton in a manuscript at the Chemical Heritage Foundation, a great example of the cursive “lb.” transmogrifying into the pound sign (upper left):

Hamlet might have written a nice letter to the caput mortuum, or dead head (lower right), an alchemical symbol for the useless residue of a chemical reaction. ChemHeritage says, “Some 16th- and 17th-century publishers had the symbol in their type cases,” and, like the pound sign, it got a stylized rendering, as seen at Wikipedia and symbols.com [!]).

The Sport in Which Nothing Happens

Jonathan Taylor writes:

I skipped the usual World Cup back-and-forth over American distaste for soccer, but for those who like to point to soccer’s scoreless ties and whatnot: According to the Wall Street Journal, the average NFL game has an average of 11 minutes of play (compared with 67 minutes of “players standing around”).

(via Felix Salmon’s Counterparties)

A Prediction Worth Taking Note Of: Marginal Revolution, Indeed

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Tyler Cowen writes:

In the longer run I expect “annotated” books will be available for full public review, though Kindle-like technologies. You’ll be reading Rousseau’s Social Contract and be able to call up the five most popular sets of annotations, the three most popular condensations, J.K. Rowling’s nomination for “favorite page,” a YouTube of Harold Bloom gushing about it, and so on.

The Times Appoints a ‘Gimlet Eye’: Guy Trebay Covers the Riprap

Jonathan Taylor writes:

“DOES anyone remember that, long before Madonna was a zillionairess with a fake British accent, she used to dance at the Roxy with a posse of Latino b-boys?” asked The Times‘s Guy Trebay in his April 7 profile of Paper magazine coeditor Kim Hastreiter. (Hastreiter does.)

Does anyone remember that, since long before becoming a fashion writer at The Times—and turning out some admittedly not-unmockable trend pieces there—Trebay has been a keen collector of the throwaway lines and gestures that take place well out of New York City’s spotlight? I do. His Hastreiter piece is a bit of a puff. But it apparently inaugurated a new rubric for his pieces, The Gimlet Eye, portending, I hope, a resurgence of rangier columns like those I used to cut out from The Village Voice with scissors.

Soon after Trebay joined The Times, a piece on “mopping,” or organized shoplifting of designer clothes—featuring a “transgendered person” named Angie E.—promised to bring to the paper’s ludicrously straight-faced fashion writing a bit of the unruly gentility Trebay had cultivated at the Voice. But as the years passed, I thought the Trebay I followed was slowly fading into the patterned wallpaper of the Sunday striving section.

To be sure, his fashion criticism has kept its zing, as in a recent Fashion Diary from Paris, in which he likens Ingrid Sischy, self-described as “triste” and yapping haplessly for Karl Lagerfeld after the Chanel show, to a baby seal stranded on an ice floe.

But in this past Thursday’s Gimlet Eye, Trebay reprises his Voice role as a one man Walk of the Town, feeling for the worn seams of the city’s public facades that betray its private dilemmas. Trebay gets predictable mileage from the presence of a safari game guide at a party at the Pierre. But it’s the second half of the column’s high society/New York freak dichotomy that showcases his laconic empathy. On an upper-Manhattan stretch of the Hudson shoreline, he talks to “Bridget Polk, who shares a name but little else in common with a famous Warhol actress,” and who makes ephemeral sculptures there by balancing local rocks atop each other [UPDATE: here’s Bridget’s “rock work” at her own site.] As in Trebay’s old collections of scraps of telephone conversations in the Voice, Trebay catches New Yorkers at their most ringingly Beckettian:

“People watch and watch and then they work up the courage to ask a question,” she said. And what do they ask? “They say, ‘Do you do these here?’ ”

The sculptor laughed then, as she does a lot, at the absurdity of other people and her own. “People say, ‘Do you use glue?’ ”

They ask whether she assembles the sculptures first and brings them with her to this stretch of shoreside riprap….

Still, she added, “I get more attention for this than anything I’ve ever done.”

Plus, I learned the word riprap—previously used in the Times only three times according to an archive search, all in connection with bridge collapses (unless you count a star racing horse of 1926–27, Rip Rap).

I Guess We’ve Got That Speed-of-Light Thing Figured Out: Google Queries Around the World

Jonathan Taylor writes:

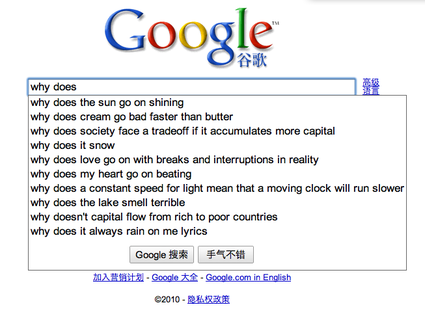

There’s been a lot of fun lately looking at Google’s search query completion suggestions (what’s the better phrase for those?). With the hullaballoo about Google in China, I realized I hadn’t yet seen comparisons of these searches across international Google sites. To wit: Here’s what comes up on Google.com.hk (Hong Kong) when you type in “why” (in English):

Um, are you ready for the U.S. site’s questions?

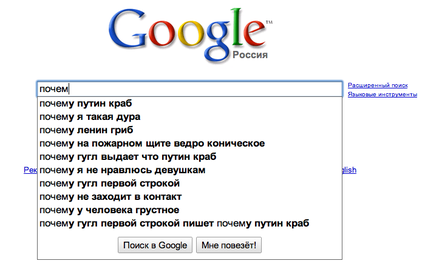

Meanwhile, the Russian Google site’s top query—”Why is Putin a crab”—is itself the subject of other queries, asking why that is the case. (There’s an answer somewhere behind the wall at the Moscow Times):

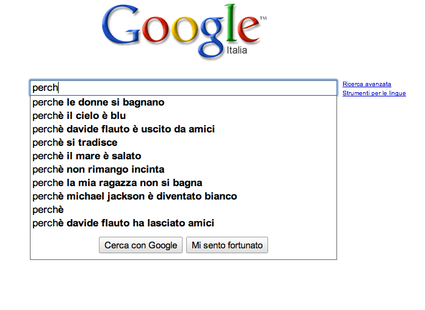

And in Italy, the questions include both “Why do women bathe?” and “Why doesn’t my girlfriend bathe?” (and “Why did Michael Jackson become white?”):

Any linguists care to tackle other foreign Google sites?