_Pollux writes_:

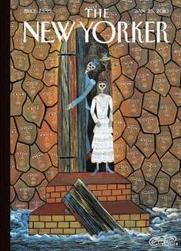

The cover for the January 25, 2010 issue of _The New Yorker_ was created by a Haitian artist, “Frantz Zephirin.”:http://www.haitian-art-co.com/artists/fzephrin.html Zephirin, according to the Contributors page, “lives on a mountain overlooking the village of Mariani, not far from the epicenter of the earthquake that struck the country on January 12th.”

From his mountaintop, Zephirin has a clearer, closer view of the tragedy that manifests itself in an abstract vision of the afterlife. On _The New Yorker_ website, Blake Eskin has written a “Cover Story”:http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2010/01/cover-story-frantz-zephirin.html on Zephirin’s piece. As Eskin points out, Zephirin’s cover was painted in 2007. Nevertheless, its symbolism and its associations with life and death are particularly appropriate for this 2010 cover, in view of the enormous losses and tragedy associated with the recent earthquake.

On _60 Minutes_, we see construction equipment scooping up the dead from the tragic earthquake, and piles of nameless bodies lying in a flattened cityscape. We hear numbers and more numbers: the number of casualties, the earthquake’s magnitude, the amount of monetary aid pouring in, the numbers to call, the number of troops sent by various governments, the number to which we can send text messages in aid of the disaster. We hope it is not so bad as the initial reports say, and realize that it is, in fact, worse.

Zephirin’s cover, called “The Resurrection of the Dead,” is an affirmation of the individuality of those who have perished in the disaster. Instead of numbers or piles of bodies, we see faces, many faces, with eyes and mouth open. According to “one website”:http://www.haitian-art-co.com/artists/fzephrin.html, Zephirin’s work is “characterized by its bright colors, patterns, tightly compacted compositions; and by the human figures with animal heads, which represent his cynicism for the ruling body.”

Instead of mangled bodies, we see beautiful faces, and each face is slightly different from the next. The expressions that we see are neither particularly happy nor sad, nor particularly masculine nor feminine. As androgynous as an angel, each face looks out from variously-shaped, interlocking tiles that hold up the vast vault of the afterlife. As Elizabeth McAlister points out in Eskin’s Cover Story, “the unblinking faces of the spirits of the recently dead. Just crossed over, they still have eyes, which are the blue and red of the Haitian flag.”

Through the open door, we see darkness and cobwebs. At first, I believed this to be a vision of hell, inhabited by grinning skeletal figures, one of whom wears a military uniform, representing military misrule and intervention, both internal and external. The other figures are dressed in clothing of the upper bourgeois. The female skeleton is similar to the figures one sees in a Frida Kahlo painting.

But it not so much hell as a border crossing between life and death. As Eskin’s piece points, gallery-owner Bill Bollendorf identifies the three skeletal figures in the doorway as representing the Guédé, “members of a family of spirits who guard the frontier between life and death. The woman in the wedding dress is Gran’ Brigitte, and the man in the blue uniform is her husband, Baron Samedi.”

Zephirin’s skeletal inhabitants open the wooden door that marks the boundary line. They grin triumphantly. The destructive power of the natural world, worsened by decades of misrule and corruption, has triumphed for the moment.

Debris, in the form of a wooden board, washes against the steps that lead to the this border crossing. The fast currents of this version of the River Styx will no doubt wash the debris away. Time moves the currents. And soon the door will close.

But the faces will remain forever, looking at us, asking us not to forget them.