Monthly Archives: February 2010

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: iPadded Cell

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: As Good As It Gets?

Hapworth 16, 1924: The Screenplay

_Pollux writes_:

For many, J.D. Salinger’s short story “Hapworth 16, 1924” is a story that one feels obliged to read, if only to see what all the fuss is about. It certainly makes easier reading than Joyce’s _Finnegans Wake_, but for readers looking for structure and narrative, Hapworth may be a disappointment.

Nevertheless, Hapworth remains an object of wonder, due to the fact that it is the last piece of work that Salinger published. Its aura is increased by its inaccessibility in print, although if you have access to The New Yorker Digital Reader, you may read it in full in the June 19, 1965 issue. Just log in, turn the digital pages to page 33, and smile at the 1960s ads for booze, vacation spots, and Woody Allen’s “laugh record” (Volume 2).

Salinger’s deal with Orchises Press to publish Hapworth collapsed like a pack of cards.

Whither Hapworth? For fun, I’ve given myself the difficult and unsanctioned assignment of trying to adapt Hapworth for the screen.

As this piece in _Slate_ “points out”:http://www.slate.com/id/2242990/, adapting any work by Salinger is an impossibility due to legal and artistic difficulties (although an undercurrent of Salinger-like characters and inspiration has existed in American cinema since the publication of _Catcher in the Rye_).

How should I adapt Hapworth? Beads of sweat roll down my forehead.

Like Nicolas Cage’s character in _Adaptation_, I feel that coffee and a muffin may help me write, but then again, I could reward myself with those items after I do some solid writing. I need to get to work.

Where does one begin?

INT. BUNGALOW 7. CAMP SIMON HAPWORTH.-DAY.

The BUNGALOW is sparsely furnished and decorated, save for some PRINTS on the wall that feature, in turn, Tolstoy, the Hindu goddess GÄyatrÄ«, Cervantes, Balzac, and Flaubert.

Below the prints, we see SEYMOUR, a boy of seven. He scribbles furiously on sheets of lined paper. Suddenly, he stops and picks up the last part of the letter. He reads aloud from it.

_SEYMOUR_

Please, please PLEASE do not grow impatient and ice cold to this letter because of its gathering length!

SEYMOUR chuckles.

Or else we start with Buddy Glass:

INT. BUDDY GLASS’ ROOM-NIGHT.

Sounds of a typewriter fill the room. PAN on BUDDY GLASS, typing. He is typing up the contents of an old, hand-written letter. An opened envelope, with a “Registered Mail” slip, sits on his desk.

PAN on the letter, the beginning of which reads: “Dear Bessie, Les, Beatrice, Walter, and Waker:…” CUT TO:

The exterior of CAMP SIMON HAPWORTH. A Maine forest.

But these points of entry may be suffering from the phoniness or mawkishness that Salinger may have despised. Finding the right child actor may also pose some difficulties. A child actor appearing in a Salinger adaptation? Whoever it would be would become an instant celebrity. The actor would become a new Seymour Glass in his own right, suffering and benefiting from the effects of instant fame.

As Emdashes editor Martin Schneider “points out”:http://emdashes.com/2010/02/why-did-salinger-once-seem-so.php, Salinger may have been the first American writer in the postwar era to explore the issues of fame and celebrity. The Glass Family siblings were celebrities who gained their fame as a result of appearing in a radio program called “It’s a Wise Child.”

Perhaps we should use a succession of child actors to play Seymour Glass, from scene to scene. Perhaps we should not use live actors at all.

“Hapworth 16, 1924” may be best adapted as a stop-motion film or a film with Japanese shadow puppets.

Camp Hapworth. Day. Several small boys, including SEYMOUR GLASS, push a cart out of the mud. They are encouraged in this exercise by MR. HAPPY.

In the car afterwards, a clay-mation (or puppet) Seymour says to a clay-mation (or puppet) Mr. Happy: “We are fairly talented singers and dancers, sir, though amateurs. If I lose my leg to gangrene, I will suggest that my father sue you. Nevertheless, since this situation is so risible, I tend to bleed less profusely, so no harm done.”

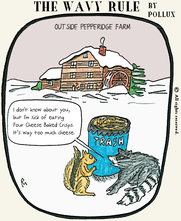

Alas, we may never see a film version or a version of Hapworth in the Indonesian shadow puppetry of “Wayang”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wayang, which Salinger may have loved. Or how about The Glass Family Cartoon, as I imagined in the drawing above?

One can dream. All this is pure experimentation and speculation, but in experimenting and speculating, we honor the author and honor the work.

_DISSOLVE TO_:

The end of this POST.

Why Did Salinger Once Seem So Modern? It Was Not Holden Alone.

Martin Schneider writes:

A few days ago, on slender justification, I concocted a post about J.D. Salinger out of a news report I happened to see about the (either cancelled or postponed) premiere of a TV game show about child prodigies. The implied connection was fatuous—and yet it sparked a thought.

Until today I have shielded myself from the response to Salinger’s death (although expect a roundup post on same anon), so I would have no way of knowing if the import of this post is trite or profound. I did notice that Garth Risk Hallberg at The Millions made the case that Salinger shifted the center of American literature from “manly” attributes like courage and honor to something more urban and intellectual—it doesn’t take much imagination to trace that particular lineage. In the broadest sense Jonathan Lethem, Jonathan Safran Foer, Jonathan Ames, David Foster Wallace, and even Philip Roth are in Salinger’s debt.

So okay—the intellect, add to it the focus on adolescence. That’s two big parts of the puzzle, obvious ones at that. But I want to draw attention to another one.

As a commenter named “liza” reminded me, “It’s a Wise Child” was based on a real radio show called “Quiz Kids” (curiously, the Wikipedia entry does not mention Salinger, as it surely should).

So what does that tell us about the Glass siblings? In short, in addition to being neurotics and prodigies and suicides, they were celebrities. I speak only for myself, but in thinking about Buddy, Franny, Seymour, and the rest of them, I tend to forget this fact—partly because Salinger’s skill, whether in dialogue or the “panoramas” of “Zooey,” keeps us so firmly in the present tense.

One of the big stories of the postwar era is the rise of fame itself as a subject for contemplation. Salinger may have been the first American writer to explore it with any thoroughness. Who else did it, before Salinger?