Martin Schneider writes:

Daniel Zalewski’s article “The Background Hum” clarified a few things in my mind about Ian McEwan. For the first time I realized that he mixes unlike traits. He’s either an exceptional writer who frequently writes bad books, or a pretty ordinary writer who had an unusually strong middle phase to his career. I favor the latter interpretation, but both will do.

Point being, let’s simplify, he’s a guy who’s written some very good books and some distinctly not-so-good books. This isn’t that unusual, I suppose, but McEwan’s kind of maxed out on his ability to do both things in the same career, which makes him cognitively difficult to get a handle on. He’s really incredibly famous—Britain’s “national author”—and very well-regarded, and he more or less escapes his proper share of abuse for the stinkers.

And by the way, no discredit to Zalewski, who repeatedly signals in the article that he understands this about McEwan, from the frank mention of Saturday‘s awkward contrivances to a friend’s “savage assessment” of McEwan’s prose to the nod to John Banville’s stinging review of Saturday in the New York Review of Books (link is courtesy of Mark Sarvas, a longtime McEwan detractor).*

Let me say now that I identify as a fan, and have for years, more or less. It’s precisely this enthusiastic self-identification that has made me notice how difficult some of his books are to defend.

Thing is, I had the luck to start with the good ones, beginning with his novella Black Dogs, which I liked a lot (even if, in retrospect, the ending is iffy). From there, in order: The Innocent, Amsterdam, Enduring Love, and Atonement, of which Amsterdam is the only true clunker of the bunch. Amsterdam is, I think, a bit scorned among McEwan enthusiasts because it won the Booker Prize, which was simply a mistake, they chose the wrong book, and it had the effect of making it difficult for his next book, Atonement, to get the support it deserved a few years later.

So, where was I? Right: Four winners in five books! I thought. Wow! This guy is the real deal! I was excited. After that, consistent with McEwan’s peculiar status, alluded to in the opening paragraph, came a surprise: the next five books I read (combining the very old and the very new) were close to an unmitigated disaster—and that group contained his best book.

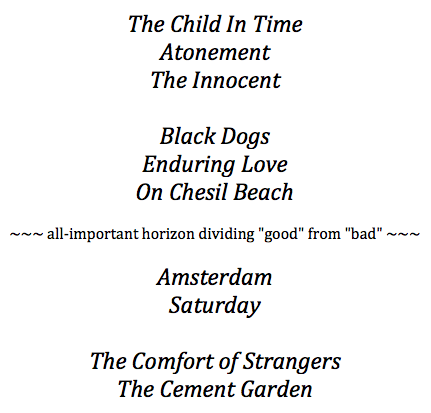

To be precise: I read The Comfort of Strangers and The Cement Garden, earlier books, unremitting and unredeemable in my view. Then two newer ones: Saturday I had no choice but to abandon, and I rather liked the slight On Chesil Beach. And then, most recently, his midcareer masterpiece The Child in Time.

So, without further ado, here’s my scoresheet, ranked from good to bad with spaces to indicate significant differences in level:

A remark or two: I really liked The Innocent, and I’m surprised it doesn’t get mentioned more often. It’s the book of McEwan’s that rises for lack of obvious flaws. And Enduring Love is justly noted for its exceptional opening section; but the book does not, in truth, deliver on that promise. It’s still one of the good ones; that and On Chesil Beach are the weakest of the good group.

Parenthetically, as I prepared this list, it struck me how much of a problem McEwan has with cute or otherwise inorganic endings, which are often clever, tacked on, tricksy. Many of the books have brief “codas” or some other framing device that jars, intentionally, with the main part of the book. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

A clue to McEwan’s combination of successes and failures may lie in an impression of mine, at least, that he is especially beloved by a certain kind of reader who hasn’t always read that many top-notch novels; it’s hard to tell. McEwan is a little too good to be the “mere” poster boy for literary striving by the unsophisticated. And yet the people I know who have read really deeply (I am not counting myself in that group) don’t especially care for him.

I have a friend who amply qualifies as a person of that sort, and a few months ago we were discussing big-deal Anglo-American writers: Roth, McEwan, Mailer, D.F. Wallace, Vollmann, Amis, people like that. And at a certain point, apropos of nothing, implicitly addressing my McEwan fandom, she suddenly spat, “I mean—On Chesil Beach—” and I can’t rightly remember if her next utterance was “Ugh!” or “Come on!” but that should suffice to express her intended meaning.

On Chesil Beach? I thought. The thing’s not crap. It’s won awards. It was rather well turned. Small, slight, sure. But certainly pretty good.

And yet, and yet—in the meantime, I’ve come to understand her a little, I think. That business of being Britain’s “national author,” for one thing. Is it possible for a novelist to have a lamer identity? It’s worse than Michael Jackson’s insistence on being called the King of Pop. At this very moment McEwan, having completed a novel “about” 9/11, is off putting on the final touches of his novel about climate change. Saturday had few recognizable human beings, I don’t expect this next one to have any, either, for what I should think are obvious reasons.

Similarly, this business of disdaining literary values for scientific rigor…. it’s a bit much. The irony is that McEwan’s virtues are precisely literary ones, not intellectual ones.

For he does have virtues. His writing on the sentence level can be awfully good. And his reputation for a certain kind of sinister tension is well deserved. He’s got a little in common with Paul Auster, maybe—very good on the sentence level, with a good dose of high seriousness of an almost modernist kind, and with terrific narrative drive.

But he’s got something else. At his best, McEwan excels at a certain sort of wonderfully daring, original, and apt moment that is extraordinarily satisfying. He possesses the imagination to invent, sheerly invent, an audacious and yet very human detail that somehow brackets the artificiality of the rest of the novel and, indeed, of all fiction. The business with the balloon in Enduring Love is an example, but an even better one is the scene late in Black Dogs in which a serious confrontation in a French restaurant is unexpectedly undone by an absurdly misfired utterance. The Innocent and Atonement have something of this quality as well, situations of sufficient potency that they radiate worthiness to every other aspect of the book in question. What makes The Child in Time the best of McEwan’s books is that he was able to spread that effect across so much of the narrative, rather than isolate it to a single scene.

As I said before, McEwan had a helluva hot streak there in middle age. He’s written a short stack of very good books. You should go read those. And the rest? You’re on your own.

*) My memory of McEwan’s reception at The Elegant Variation was in error.

Emdashes

Modern times between the lines