Martin Schneider writes:

Credit Twitter users supergork and echidnapi with the catch.

In the May 31, 1976, edition of The New Yorker, there appeared a “casual” (what today would be filed under “Shouts & Murmurs”) by Richard Leibmann-Smith satirizing the hullabaloo surrounding awards ceremonies. Leibmann-Smith spent page 31 (subscribers only) musing on the following scenario: what if the “Academy” in “Academy Awards” signified the American Academy of Medicine? What if there were a “Jonas” instead of an “Oscar,” with the categories Best Disease, Best Symptoms, Best Virus, and Best Potential Epidemic? Riffing on the most recent Oscar winner, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which had also effected a sweep of all the major categories just two months earlier, Leibmann-Smith chose as his awards juggernaut “Swine flu,” as in the piece’s title (prepare wince reflex), “Swine Flu Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

On the intersection of Twitter and swine flu, Randall Munroe expresses more amusingly something I had noticed as well.

Category Archives: The Squib Report

Steve Coll Blogs the Stimulus and Earns Our Admiration

Martin Schneider writes:

Shortly after the Stimulus Bill was passed in February, Steve Coll began a project of reading through the entire legislation and blogging about it at newyorker.com. This website has ignored that worthy development for far too long, and now, almost as if to remind us to post about it, Coll has done an invaluable “diavlog” with Michael Grabell of ProPublica, which is also covering the stimulus in great detail.

The stimulus bill is one of those subjects that probably a great many people wish they knew more about; probably far too many of us are exposed to media speculation over the politics instead of actual analysis of the bill’s real-world effects. If that describes you, I think the diavlog dialogue is an excellent starting point for further investigation. If nothing else, it will introduce you to a handful of overriding themes, as well as act as a prod to read the coverage Coll and Grabell are providing elsewhere.

On that subject, if you haven’t been reading Coll’s stimulus updates, we provide a public service of linking you to Coll’s “Blogging the Stimulus” posts. But we’ll go that extra step further and link to each of the posts, to provide that little bit of overview that might make it easier for some to dive in.

March 2, 2009: “Blogging the Stimulus Bill”

March 4, 2009: “Notes on Agriculture”

March 6, 2009: “The Census-Taker Full Employment Act”

March 6, 2009: “Policing the Recovery”

March 9, 2009: “Where No Stimulus Has Gone Before”

March 11, 2009: “Cooling Off Soldiers”

March 19, 2009: “Microloans for Unemployed Journalists?”

March 23, 2009: “Made in the Homeland”

March 31, 2009: “Old School Stimulus”

April 3, 2009: “Role Models”

April 13, 2009: “Smart Medicine”

April 17, 2009: “Schooling the Stimulus”

April 21, 2009: “Investing in Soldiers”

Omit Needless Controversy: Fifty Years of Strunk and White

Martin Schneider writes:

The fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style was last Thursday. I’m a copyeditor by trade, so one might say professionally implicated. My love of accuracy compels me not to pretend that the book is universally admired by all those who love words; far from it. (So much strong feeling!) For my part, I’ll just say it communicated certain things I needed to know at certain times in my life, and for that I am grateful.

A less contentious issue is E.B. White, who is always worth celebrating. Levi Stahl of I’ve Been Reading Lately has been lately reading his letters (you know, in a book, not in his desk drawer or anything), which sound delightful.

Oh yes, I almost forgot: subscribers can read the original 1957 article that sparked the publication of the book.

Introducing the Jeff Spicoli Amendment: Our Unserious Media

Martin Schneider writes:

This week was dominated by two news stories that our national commentators apparently could not cover without breaking into a gale of snickers: I refer to the problem of maritime raiders interfering with the merchant vessels of various nations (“pirates”) and the nationwide grassroots protests over the unfairness of the Obama administration’s tax policy and recent financial bailouts (“teabagging”).

Now we see how any political organization, be it the White House, Congress, the Republicans, the Democrats, can avoid scrutiny over a touchy subject that it wants to introduce into the public discourse: link it to some amusing word that reduces every commentator to a twelve-year-old. We’ll have the Cheech and Chong Estate Tax Legislation and the Pauly Shore Pollution Amplification Program (Pollux, there might be a cartoon in this theme for you).

Meanwhile, the G20 economic summit reminded me of another pet peeve. Our newscasters have given up the pretense that other countries, cultures, and particularly languages exist. How many times did CNN and its competitors refer to a president of France named sar-KOZE-ee? As far as I know there is no such person, his name is sar-ko-ZEE. Did anyone even try to suggest, in the prounciation of his name, that he wasn’t raised in Bayonne? I may have missed it. It wasn’t so much the butchering of his name that bothered me as the lack of awareness that it was happening.

It reminded me of circa 2006, when hardly a day would pass without some TV commentator pronouncing the name of the prominent Iranian anti-Semite thus: “Ach-men-whatever his name is.” Like my quasi-countryman Arnold Schwarzenegger, Ahmedinejad’s name (not difficult to master if you spend more than 15 seconds in the attempt) became the butt of the joke. Only this time it wasn’t the moviegoer in the street who was proudly claiming the mantle of ignorant provincialism; it was the very people who claim to bring us the world. And that’s a damn disgrace.

Brace Yourself for Bruno, the New Yorker Way

Martin Schneider writes:

Sacha Baron Cohen’s new movie Bruno (or Brüno), featuring his “flamboyantly gay” Austrian fashion scenester character, is due out this summer. The recently released trailer starts with a barrage of pullquotes, one of the first of which is “Lavatorial!” and is credited to “Anthony Lane, The New Yorker” (it’s perfectly accurate).

Like any good fashionista, the trailer jokes that Borat is “so 2006.” But sadism-tinged guerrilla culture-war humor (no matter how brilliant) really does seem incredibly 2006, no? It’ll be interesting to see if squirming squares will play as well in the age of Obama, now that those squares are worried about their jobs, mortgages, retirement plans. Is it homophobia or parody of same? Ah, who can tell. If you missed it the first time around, George Saunders’s take on Borat was one of the sharpest.

I’m writing this from Austria, Bruno’s supposed homeland, where Joseph Fritzl pleaded guilty a couple of weeks ago. Bruno’s definitely a step up, PR-wise.

Call for Information / Opinion: Lyll Becerra de Jenkins

Martin Schneider writes:

On one of our most popular pages (it attracts a lot of search engine traffic), a reader called Arya Breton contributes a terrific bit of context for a mentioned writer:

Lyll Becerra de Jenkins was an extraordinary journalist, writer of fiction and teacher of writing. She wrote three books—The Honorable Prison, Celebrating the Hero, and So Loud a Silence. Her short stories, such as Tyranny, which later evolved into the prize-winning YA fiction, The Honorable Prison, were masterful. During a time when everyone from Latin America was writing in the style of the magical realists, she set herself apart. A resident of New Canaan, Connecticut, where she emigrated with her North American husband and five children, she seeped herself in the writing of the Brits and North Americans and developed her own distinct voice and approach to story-telling. Frances Kiernan of The New Yorker, who was her editor in the 70s, said her writing had “unique tension,” a flamenco style.

Sounds fascinating! I notice my public library has copies of The Honorable Prison and Celebrating the Hero. I’d be happy to spark a Lyll Becerra de Jenkins revival. If you are a fan or simply know something about her, please write in. And that includes you, Arya Breton!

If Pnin is In, Does That Mean Kilgore Trout is Out?

Martin Schneider writes:

Last week we posted the syllabus of Zadie Smith’s fiction seminar at Columbia University. I noticed that one of the books was Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin. It triggered a memory: last October, on a New Yorker Festival panel with Hari Kunzru and Peter Carey, Gary Shteyngart answered moderator Peter Canby’s request to name a favorite or most influential work by intimating that he reads Pnin “once a month.”

I know the journalistic credo has it that once is an occurrence, twice a coincidence, thrice a trend. I have only the two mentions, yet nevertheless cry “Trend!” My impression is that Pnin is relatively obscure; it doesn’t come up in conversation much, at least not with the people I know. I’ve read four Nabokov novels, and Pnin isn’t one of them. As far as I know, Pnin is noteworthy for being somewhat more autobiographical than most of Nabokov’s work, as it is about a Russian emigre who is working in the United States as a professor.

So much for this focus group of one. Have you been running into Pnin lately?

As it happens, Pnin has a slight familial resonance for me; my father used to tell how impressed he was with the original Pnin stories when they appeared in The New Yorker in the mid-1950s, so it feels like I’ve been aware of it for years. I’m now traveling and have a limited number of books at my disposal, but, triggered by Shteyngart perhaps, elected to bring that one with me. I’ll get to it soon.

Thru You, Through the New Yorker Blog, to Most of the Rest of Us

Martin Schneider writes:

A friend sent me a link to Kutiman’s marvelous “Thru You” website, and now I’m all excited about it. After the initial delight had worn off, I thought, “I wonder if Sasha Frere-Jones knows about this?”

Relax, man, his blog was on it way back last week (an eternity in meme propagation terms). Unsurprisingly, what he has to say is well worth a look.

But more to the point, go visit Thru You.

A Cheat Sheet for Ian McEwan, Confounding Modern “Master”

Martin Schneider writes:

Daniel Zalewski’s article “The Background Hum” clarified a few things in my mind about Ian McEwan. For the first time I realized that he mixes unlike traits. He’s either an exceptional writer who frequently writes bad books, or a pretty ordinary writer who had an unusually strong middle phase to his career. I favor the latter interpretation, but both will do.

Point being, let’s simplify, he’s a guy who’s written some very good books and some distinctly not-so-good books. This isn’t that unusual, I suppose, but McEwan’s kind of maxed out on his ability to do both things in the same career, which makes him cognitively difficult to get a handle on. He’s really incredibly famous—Britain’s “national author”—and very well-regarded, and he more or less escapes his proper share of abuse for the stinkers.

And by the way, no discredit to Zalewski, who repeatedly signals in the article that he understands this about McEwan, from the frank mention of Saturday‘s awkward contrivances to a friend’s “savage assessment” of McEwan’s prose to the nod to John Banville’s stinging review of Saturday in the New York Review of Books (link is courtesy of Mark Sarvas, a longtime McEwan detractor).*

Let me say now that I identify as a fan, and have for years, more or less. It’s precisely this enthusiastic self-identification that has made me notice how difficult some of his books are to defend.

Thing is, I had the luck to start with the good ones, beginning with his novella Black Dogs, which I liked a lot (even if, in retrospect, the ending is iffy). From there, in order: The Innocent, Amsterdam, Enduring Love, and Atonement, of which Amsterdam is the only true clunker of the bunch. Amsterdam is, I think, a bit scorned among McEwan enthusiasts because it won the Booker Prize, which was simply a mistake, they chose the wrong book, and it had the effect of making it difficult for his next book, Atonement, to get the support it deserved a few years later.

So, where was I? Right: Four winners in five books! I thought. Wow! This guy is the real deal! I was excited. After that, consistent with McEwan’s peculiar status, alluded to in the opening paragraph, came a surprise: the next five books I read (combining the very old and the very new) were close to an unmitigated disaster—and that group contained his best book.

To be precise: I read The Comfort of Strangers and The Cement Garden, earlier books, unremitting and unredeemable in my view. Then two newer ones: Saturday I had no choice but to abandon, and I rather liked the slight On Chesil Beach. And then, most recently, his midcareer masterpiece The Child in Time.

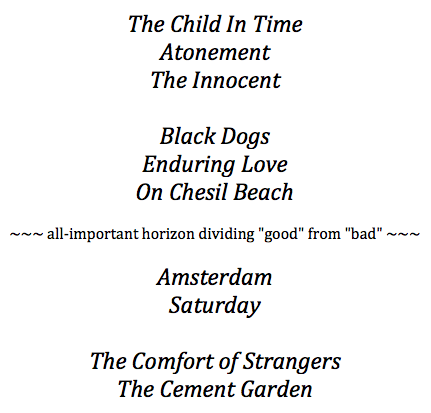

So, without further ado, here’s my scoresheet, ranked from good to bad with spaces to indicate significant differences in level:

A remark or two: I really liked The Innocent, and I’m surprised it doesn’t get mentioned more often. It’s the book of McEwan’s that rises for lack of obvious flaws. And Enduring Love is justly noted for its exceptional opening section; but the book does not, in truth, deliver on that promise. It’s still one of the good ones; that and On Chesil Beach are the weakest of the good group.

Parenthetically, as I prepared this list, it struck me how much of a problem McEwan has with cute or otherwise inorganic endings, which are often clever, tacked on, tricksy. Many of the books have brief “codas” or some other framing device that jars, intentionally, with the main part of the book. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

A clue to McEwan’s combination of successes and failures may lie in an impression of mine, at least, that he is especially beloved by a certain kind of reader who hasn’t always read that many top-notch novels; it’s hard to tell. McEwan is a little too good to be the “mere” poster boy for literary striving by the unsophisticated. And yet the people I know who have read really deeply (I am not counting myself in that group) don’t especially care for him.

I have a friend who amply qualifies as a person of that sort, and a few months ago we were discussing big-deal Anglo-American writers: Roth, McEwan, Mailer, D.F. Wallace, Vollmann, Amis, people like that. And at a certain point, apropos of nothing, implicitly addressing my McEwan fandom, she suddenly spat, “I mean—On Chesil Beach—” and I can’t rightly remember if her next utterance was “Ugh!” or “Come on!” but that should suffice to express her intended meaning.

On Chesil Beach? I thought. The thing’s not crap. It’s won awards. It was rather well turned. Small, slight, sure. But certainly pretty good.

And yet, and yet—in the meantime, I’ve come to understand her a little, I think. That business of being Britain’s “national author,” for one thing. Is it possible for a novelist to have a lamer identity? It’s worse than Michael Jackson’s insistence on being called the King of Pop. At this very moment McEwan, having completed a novel “about” 9/11, is off putting on the final touches of his novel about climate change. Saturday had few recognizable human beings, I don’t expect this next one to have any, either, for what I should think are obvious reasons.

Similarly, this business of disdaining literary values for scientific rigor…. it’s a bit much. The irony is that McEwan’s virtues are precisely literary ones, not intellectual ones.

For he does have virtues. His writing on the sentence level can be awfully good. And his reputation for a certain kind of sinister tension is well deserved. He’s got a little in common with Paul Auster, maybe—very good on the sentence level, with a good dose of high seriousness of an almost modernist kind, and with terrific narrative drive.

But he’s got something else. At his best, McEwan excels at a certain sort of wonderfully daring, original, and apt moment that is extraordinarily satisfying. He possesses the imagination to invent, sheerly invent, an audacious and yet very human detail that somehow brackets the artificiality of the rest of the novel and, indeed, of all fiction. The business with the balloon in Enduring Love is an example, but an even better one is the scene late in Black Dogs in which a serious confrontation in a French restaurant is unexpectedly undone by an absurdly misfired utterance. The Innocent and Atonement have something of this quality as well, situations of sufficient potency that they radiate worthiness to every other aspect of the book in question. What makes The Child in Time the best of McEwan’s books is that he was able to spread that effect across so much of the narrative, rather than isolate it to a single scene.

As I said before, McEwan had a helluva hot streak there in middle age. He’s written a short stack of very good books. You should go read those. And the rest? You’re on your own.

*) My memory of McEwan’s reception at The Elegant Variation was in error.

The Unfinished Pale King: Guilt, Boredom, Acceptance, and Hope

Martin Schneider writes:

I’m still not all that comfortable about reading an unfinished work by a writer as fiercely scrupulous as David Foster Wallace was, but after reading the D.T. Max article and pondering his two great, flawed novels and his three great, flawed short story collections, I wonder if this isn’t, inadvertently, sadly, unwittingly, the proper (if that can be the right word) form for a work of the type Wallace was attempting, a meditation of the salvational qualities of boredom, using as a vehicle the IRS and the U.S. tax code.

I thought I would never be able to read The Pale King. Now I think I probably will be able to.