Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

Monthly Archives: January 2009

Random Profiler: Winthrop Sargeant on Glynn Ross, 1978

In this installment (see this “post”:http://emdashes.com/2008/12/random-profiler-liebling-on-ch.php for an introduction to the “series”:http://emdashes.com/mt/mt-search.cgi?blog_id=2&tag=Random%20Profiler&limit=20), the roulette wheel landed on Winthrop Sargeant’s 1978 “Profile”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1978/06/26/1978_06_26_047_TNY_CARDS_000326739 on Glynn Ross. This was very much the sort of Profile that I was hoping for when I started this project: an interesting subject previously unknown to me.

Ross was the director of the Seattle Opera starting in the 1960s, and he did a lot to popularize the form in the northwestern metropolis by using unconventional promotional techniques and generally being smart about his task. It was his policy to perform all operas in the original language and in English, an idea that shouldn’t be as rare as it apparently is. He was also very shrewd about attracting established stars to remote and (then) unfashionable Washington State for single productions. On this, Sargeant quotes Ross: “An artist wants four things: one, a chance to do something that requires the best of his abilities; two, the opportunity to grow by singing different roles; three, prestige; and four, a paycheck.”

Ross staged the first American production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle that didn’t take place at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, a production that helped establish Seattle as a major center of Wagner interest. He used colorful slogans directed at the new wave of youthful customers, such as “La Bohème: Six old-time hippies in Paris,” “Roméo et Juliette: Two kids in trouble, real trouble, with their families,” and (cue bad-pun grimace) “Get Ahead with Salome.” In 1971, just a couple years after it was written, the Seattle Opera was the first reputable opera house to stage The Who’s _Tommy,_ with Bette Midler in a leading role, a detail the magazine omits. (In a perfect world, we’d have some YouTube footage of that production!) In baseball, the analogous figure would be “Bill Veeck,”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Veeck roughly.

Sargeant’s work here is a reminder of how conservative the form can sometimes be, which is not a criticism. The Profile starts by establishing the subject’s Profile-worthiness and then segues to the subject’s background, relying a good deal on lengthy quotation from the subject. It’s not “exciting,” but it does the job.

Reading the Profile, it’s difficult not to think of Peter Gelb, general manager of the Met since 2006 and a New Yorker Conference “attendee”:http://emdashes.com/2008/05/the-new-yorker-conference-is-q.php in 2008. Gelb has been phenomenally successful in finding new audiences for Met productions, and his main weapons have been the appearance of filmed versions of current productions in our nation’s multiplexes and fresh thinking on the nature of those productions, both in their selection and in the emphasis on accessability. A quick search at Google suggests that not too many people have suggested the parallels between Ross and Gelb, but they seem pretty obvious to me (not that I’d be aware of any other similar figures).

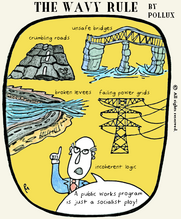

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Breakfast at Tiffany’s

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

The Unlikeliest Gladwell Article: Thoughts on David Galenson

Isn’t it time for another Malcolm Gladwell post? A few weeks ago Tina Roth Eisenberg at my favorite design blog, “Swissmiss,”:swissmiss.typepad.com/ linked to this swell “video”:http://www.aiga.org/content.cfm/video-gain-2008-gladwell of Gladwell discussing Fleetwood Mac and David Galenson’s ideas about creativity at AIGA’s GAIN Conference in October, the same month that the _The New Yorker_ ran Gladwell’s “article”:http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/10/20/081020fa_fact_gladwell about him.

Galenson is an economist who developed a theory of creativity that states that artistic innovators mostly come in two packages, of which the exemplars are Picasso and Cézanne. Picasso made his mark as a young man, and his pictorial brilliance seemed to come quite naturally; Cézanne’s success came much later in life, and his breakthroughs seemed the result of a great deal of sustained effort and slow experimentation. As far as I can tell, neither Galenson nor Fleetwood Mac is mentioned in “Outliers,”:http://www.amazon.com/gp/reader/0316017922/ref=sib_dp_srch_pop?v=search-inside&keywords=hedgehog&go.x=0&go.y=0&go=Go at least according to a search on Amazon’s OnlineReader (I have not obtained my own copy of the book yet), this even though the subject seems to fit in perfectly well with the book’s themes.

Then you have the interesting fact that, as Jason Kottke “pointed out”:http://www.kottke.org/08/08/old-masters-and-young-geniuses several months ago, this Galenson article was, according to _The New York Times,_ actually “rejected”:http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/15/business/15leonhardt.html?pagewanted=all by _The New Yorker_ in 2006, the first Gladwell pitch to receive the heave-ho. David Leonhardt’s article quotes Gladwell’s “editor” pooh-poohing Galenson’s spiel and asking Gladwell whether he is “crazy.” (What editor could this be? Surely not David Remnick?)

Galenson’s division of artists into blazing young “conceptual innovators” and older “experimental innovators” reminds me a bit of “The Hedgehog and the Fox,”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hedgehog_and_the_Fox Isaiah Berlin’s famous appropriation of the ancient Greek poet Archilochus (admit it, you knew that this blog would eventually work Archilochus in somehow). Archilochus wrote that “the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing”; Berlin’s idea was that Dostoevsky was a hedgehog and Tolstoy a fox who wished that he were a hedgehog. Somehow the conceptual innovators seem like hedgehogs to me, and experimental innovators like foxes. Galenson, by the way, does cite the hedgehog/fox pairing in his book “Old Masters and Young Geniuses”:http://books.google.com/books?id=aj43lvAIJIcC&pg=PA181&lpg=PA181&dq=galenson+hedgehog&source=web&ots=gEl9FVxIgR&sig=KP92wQybfyltDF-XeBMalDexxhg&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=3&ct=result#PPA181,M1.

There aren’t that many bands whose career arc is that similar to Fleetwood Mac, in my opinion (rock is a young person’s game), but it happens that my favorite band in the world, the “Wrens,”:http://www.wrens.com/ fits Galenson’s schema to a T. Their masterpiece, The Meadowlands, was four years in the making and came fully nine years after their debut. And it matches up with Galenson’s “experimental innovators”—the band tinkered so extensively with the tracks that the band forced themselves to destroy the master tapes as a way of committing to a truly final cut.

Another one that comes to mind is Pulp. Pulp’s breakout album was “His ‘N’ Hers,”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/His_%27n%27_Hers which came out in 1994; their first album came out in 1983, eleven years earlier. That’s quite an incubation. All of their good albums came after their tenth year in the business.

By the way: A few days before Christmas, Gladwell appeared on _The Charlie Rose Show,_ and the resultant “segment”:http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/9855 features both Gladwell and Rose at their best. I also love the show’s new—I think—black website, which seems to reference the show’s trademark table-immersed-in-blackness aesthetic.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Medieval Times

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

J.D. Salinger Turns 90 Today

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Charles McGrath has an excellent article in The New York Times on J.D. Salinger’s last published piece, “Hapworth 16, 1924“. The 25,000-word novella appeared in the June 19, 1965 issue of The New Yorker, and never anywhere else. Thanks to the magic of the Digital Edition, it’s more accessible now than ever before. (Many of Salinger’s other classic works first appeared in the magazine too, although you’d search in vain for Catcher in the Rye because, as Louis Menand pointed out in a 2001 retrospective, the magazine rejected it.)

McGrath has some perceptive things to say about the charm of Salinger’s writing, and why it remains influential. He also hits the nail on the head when he talks about the chief drawback of Salinger’s chronicles about his fictional family, the Glasses:

The very thing that makes the Glasses, and Seymour especially, so appealing to Mr. Salinger— that they’re too sensitive and exceptional for this world— is also what came to make them irritating to so many readers.

Nevertheless, I’d like to wish this great American writer a very happy birthday.