Jonathan Taylor writes:

Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity is the Museum of Modern Art’s first major Bauhaus exhibit since 1938. Janet Flanner (“Genet”) wrote in 1969 about a Bauhaus retrospective at the Musée National d’Art Moderne (then on the Ave. du Président Wilson) and the nearby Musée Municipal d’Art Moderne in Paris, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the school’s founding. Flanner wrote that the show was to go on to Chicago. The article gives little detail about the contents of the show—it’s more of a primer on the great artists the Bauhaus gave the world: Kandinsky, Klee, Mies.

The new MoMA show is more about what great artists gave to the Bauhaus. Many reviewers have felt the need to cite an invented consensus perception of the Bauhaus: in the words of the Times‘s Nicolai Ouroussoff, “tubular steel furniture, prefabricated housing, ranks of naïve utopians and Tom Wolfe’s withering disdain for all of the above. A show about the Bauhaus? No thanks. Who, after all, really needs to see another Breuer chair?”

But even if one’s opinion going in is less hostile, the chance to see so many products of Bauhaus design, craft and manufacture is a revelation, if one has never had the chance to experience their sheer materiality in person. The school’s emphasis on the properties of their materials—metal, wood, glass, and in the case of the playful photomontages, paper—lends these objects, in their contemporary context, a real warmth (aided somewhat by the yellowing of the paper exhibits, and the patination of metal). Even after the Bauhaus’s turn away from its Expressionist roots in nostalgia for the premodern, and toward the stark geometry and sans-serif typography it’s better known for, there’s a wonderfully consistent presence of the earthy and decorative in the Bauhaus’s textile products and wallpapers, by artists including Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl.

For me, the highlight of the exhibit, exemplifying the quest for ingenuity and the personal touch inherent in the Bauhaus’s formation of master craftsmen and -women, is a pair of textiles whose patterns were devised by Hajo Rose using a typewriter. In one case, the pattern consists with rows of nearly interlocking typed “9”s, creating a semiabstract pattern that Alexandra Lange describes well as “letterforms turning into repetitive and almost floral scallops.” The exhibit includes both the swatches of typed paper, and the resulting textiles. I’ve looked for an image online to link to, but can’t find one. It’s just as well—this show is about what you can learn about the Bauhaus from being in the presence of its art, rather than reading about it.

Monthly Archives: November 2009

Sempé Fi: The Masquerade

_Pollux writes_:

Sometimes my approach in writing these Sempé Fi columns involves showing someone, usually not a _New Yorker_ reader, the cover of the latest issue and see what their initial reaction is. With “Chris Ware’s”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chris_Ware cover for the November 2, 2009 issue, called “Unmasked,” the reaction I received, from more than one person, was: “Yeah, that’s how people are.”

That’s how people are –meaning the parents who stand in the street depicted in Ware’s cover, their attention monopolized by their phones, rather than in their young children, who are trick-or-treating. The parents are there and not there at the same time, empty uniforms in the field of battle of parenting.

The kids are having their childhood experiences; they probably won’t remember their parents being there at all, if they remember the night at all. The parents aren’t living it. A night out trick-or-treating is a distraction from real life rather than an experience of it. Their phones are keeping them connected to what’s “real.”

The phones cast a glow upon the parents’ faces. Ware skillfully renders the artificial illumination both a masking and an unmasking. The glow turns the faces into masked faces that match the children’s actual masks, but the glow is actually casting a light upon the parents, revealing them to be what they really are: busy, unfocused, unsentimental, and somewhat selfish.

When their kids, whose faces are literally masked and facing the glow of not LCD screens but houses warm with light and candy, get their sack full of Milk Duds and M&M’s, the parents will momentarily put their phones down and move to the next house. It’s an empty ritual; it won’t make for a memorable night, both for child or for parents.

Ware leaves out the usual color and magic associated with Halloween night. Ware creates a bleak image of undecorated houses and parents focused on all the wrong things. It’s a glum procession of the masked and unmasked.

Ware’s cover works as a stand-alone visual piece, but the cover ties in with a graphic short story, also by Ware and also called “Unmasked,” that lies within the covers of _The New Yorker_. Ware manages to incorporate a lot of family drama and commentary on families within the four pages accorded to his illustrated piece.

The first panels of the short story match the image on the cover: a middle-aged woman on her iPhone 3G receiving a text from her husband Phil, who is too busy to accompany her and their four-year-old daughter on Halloween night. He’s too busy. “I was so mad. I could hardly type…” she thinks. “How many Halloweens did he suppose he’d have with his four-year-old?”

But as her young daughter innocently and happily frolics throughout the short story, the woman, too, seems to direct most of her energies and attention elsewhere. As Ware’s story unfolds, we learn that the woman’s mother lives alone since her husband died. The woman and her mother sit in the park, as the four-year-old daughter enjoys herself on a swing. There, at the park, the woman’s mother reveals that her late husband had been having an affair with his teaching assistant.

Her mother’s revelation makes the woman angry rather than sympathetic. Was her mother implying by her revelation that Phil is now cheating on her? She stops drying her daughter with a towel in order to make “a very important phone call to Daddy.”

After she finishes the call, she shrugs off such fears of an affair. “Poor mom…” she thinks, “she was still naïve in so many ways…”

And so the woman assures herself after communicating with her husband via a telephone. Who knows what her husband doing? There’s no way to tell; husband and wife never seem to be in the same room. And her daughter, while still young, will not be young for long, and perhaps will grow up with her own set of resentments and issues.

That’s how people are, and always will be, except now they have access to the fastest, most powerful phones on the market.

Cartoon Bank Overhaul: Ben Bass Blogs On Who Broke the Bank

_Pollux writes_:

All change is not growth, as all movement is not forward. So the saying goes, and _The New Yorker_’s “Cartoon Bank”:http://www.cartoonbank.com has changed, but it has not grown. The changes made, as of October 6, 2009, to the Cartoon Bank have unfortunately set it back in terms of usability, accuracy, and reliability.

Ben Bass has written a cogent “analysis “:http://benbassandbeyond.blogspot.com/2009/11/who-broke-bank.html of the overhaul, and its effect on what used to be a dependable storehouse of _New Yorker_ cartoons and covers.

It’s not just about searching easily for your favorite dog and desert island cartoons. As Bass writes, “the removal of popularity search also adversely affects the artists themselves, who get commissions on each sale.”

For my part, I’ve experienced difficulties finding such simple things as Robert Crumb’s famous 1994 “cover”:http://sexualityinart.wordpress.com/2008/03/18/robert-crumb-drawing-as-a-medium-for-analysis-of-american-culture-drawing-on-the-important-things/ that depicted his version of Eustace Tilley.

I type in “Robert Crumb” and get results that include cartoons and covers drawn by artists whose first name is Robert (e.g. Robert Tallon, Robert Kraus). But no Robert Crumb cover. And I did what everyone else will soon do: find an alternate way of looking for _New Yorker_ artists’ work.

Is every change to the Cartoon Bank a move backward? No. The site has a clean, intuitive design with “Refine Search” engines that simply need to be fine-tuned.

We’d be interested in what Emdashes readers have to say about this issue. Please post your feedback!

**Update**: As of November 11, 2009, some changes were made to the site, which include enhanced navigation, new framing options, a preview tool for customized products, and a canvas print option for covers.

Also by Ben Bass: a recent “write-up”:http://benbassandbeyond.blogspot.com/2009/10/home-and-home-series.html on The New Yorker Festival and “Avenue Queue”:http://emdashes.com/2007/10/avenue-queue-a-new-yorker-fest.php, a special 2007 Festival report.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: The Illustrated Dead Sea Scrolls

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Double Vaccination

A Report: Nixon, Oppenheimer, Faust, and John Adams at Yale

In October we were very pleased to present Jenny Blair’s account of Platon’s New Yorker Festival event. Today Blair has volunteered to bring us a detailed report of a fascinating lecture by the composer John Adams in New Haven, which occurred last week.—Martin Schneider

Jenny Blair writes:

The composer John Adams visited Yale University last week to give the prestigious Tanner Lectures on Human Values.*Â This writer attended the second of the two lectures, held at the Whitney Humanities Center on October 29. (In the first, the composer discussed Thomas Mann’s fictional composer in the novel Dr. Faustus.)

A fine-featured and slender man with arching sprouts of white hair and a gracious manner, Adams spoke to a near-capacity crowd about the way that myth informs his operas. Though he is famed in part for having dramatized Nixon’s visit to China and, more recently, for the 2005 opera Doctor Atomic, which dramatizes the hours before the first atomic bomb was detonated, Adams is annoyed when he hears himself referred to as a “political composer” or his operas called “docu-operas.” Such appellations would seem to miss the point, which is that he seeks out universal themes within the famous particular. Events in history, he said, can rise to a mythic level, and these myths are a proper hunting ground for his music. “The themes I choose,” he said, “are not simply mere news, but rather human events that have become mythology. . . . [They are] a symbolic expression of collective experience.”

“Biography, history, and science have come to constitute our own myths,” he said, naming as examples Gandhi, Babe Ruth, 9/11, and the moon landing. “Andy Warhol understood the grip that iconic images have on us, . . . [such as] Elvis with a six-shooter, the electric chair, Marilyn Monroe.”

An indispensable element of myth is the supernatural, Adams said, and there is something about the media’s incessant repetition and manipulation of images and events that supernaturalizes those events. “When they saturate public consciousness, they become totemic. . . . [Some] rise to the status of myth.” Whether we know it or not, he said, we of the electronic age are saturated in myth.

9/11 is a classic case in point. Even with the same number of deaths, he said, “had it been a one-story warehouse somewhere in New Jersey, I don’t think that totemic power would have invaded public consciousness.” The endlessly replayed video clip of the Twin Towers’ collapse, he said, was a ritualistic reenactment.

It was Peter Sellars, director of the first, highly acclaimed production of Doctor Atomic, who suggested that Adams write an opera about Nixon’s iconic visit to China. At the time, Adams had been composing music about Carl Jung, and had even made a pilgrimage to the psychiatrist’s home in Switzerland. But he recognized the story of Nixon’s trip as “full to the brim with myths.” Capitalist meets Communist. Presidential vanitas. The narratives and personae created by people in power—this story had it all. “Both Mao and Nixon had made themselves into grandiose cartoons.”

Adams read aloud a portion of Alice Goodman’s Nixon in China libretto, in which Nixon is speaking. (One suspects he held back a rip-roaring mimicry.) Then he parsed it like a poem, noting references to 1930s ballads, Chekhov, and Apollo 11. A recording of the same passage as sung by original cast member James Maddalena was then played, and Adams, as he listened, made muted conductor-like waves of his bowed head.

To critics who charge that subjects like the atomic bomb or terrorism (a subject he treated in The Death of Klinghoffer, his 1991 opera based on the hijacking of the Achille Lauro) are events too serious to be appropriate for theater, Adams replies that such things are the stuff of myth. Moreover, terrorism, with its suicide bombers and innocent victims, is already a kind of theater. And as for Trinity, “there is no more emphatic image to [sum up] the human predicament than the atomic bomb. . . . That day, science and human invention sprang instantaneously to mythic levels.” Initially, Adams said, he had wanted to draw a parallel between J. Robert Oppenheimer and the soul-selling Faust of Goethe’s drama. But he eventually came to decide that inaction during the war would have required complete pacifism and an acceptance of “a long dark night of the soul,” whereas the Los Alamos scientists were devoted to winning a war against tyranny.

Yet once they built the bomb, said Adams, “the relationship between the human species and the planet irrevocably changed. It was a seismic event in human consciousness. . . . [Humankind now had the ability] to destroy its own nest.” Indeed, the physicist Edward Teller, in a letter Adams read aloud, wrote, “I have no hope of clearing my conscience. . . . No amount of fiddling . . . will save our souls.”

The libretto of Doctor Atomic was greeted by a torrent of criticism in the press for its unusual use of both natural language (as lifted from primary sources, like letters and biographies) and poetry, as well as a perceived lack of “verismo” in some of the arias. But Adams pointed out that not all operas are like Strauss or Wagner. The arias of Monteverdi and Mozart were written purely for poetic effect and stepped out of narrative time—as did Adams’s.

The composer ended his lecture with a few words about the first act’s final aria and a video of its performance by “my wonderful, wonderful” baritone, Gerald Finley. This aria takes place the night before the Trinity test, after an electrical storm has threatened the test. The music before this had flirted with atonality, Adams said, but the aria itself is in D minor, which conveys the “noble gravitas” of the poem. The storm blows over at last, and Oppenheimer is left alone with his thoughts. He sings a lightly adapted Donne sonnet, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.” The choice of this poem reinforces Adams’s decision not to compare Oppenheimer to Faust, for in it the narrator longs to reunite with God:

Batter my heart, three person’d God; For you

As yet but knock, breathe, knock, breathe, knock, breathe

Shine, and seek to mend;

Batter my heart, three person’d God;

That I may rise, and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force, to break, blow, break, blow, break, blow

burn and make me new.I, like an usurpt town, to another due,

Labor to admit you, but Oh, to no end,

Reason your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv’d, and proves weak or untrue,

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,

But am betroth’d unto your enemy,

Divorce me, untie, or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

After thunderous applause—the kind that tempts you to stand up and start an ovation—audience members stepped up to the microphones to ask questions. Highlights, lightly paraphrased:

Q: “Please give me water—my child is thirsty” were spoken as the last words of the opera. Why?

A: I realized I needed to hear the other side. Those words came from John Hersey’s Hiroshima. The woman who did the recording was a California university student, Japanese, and had a lot of piercings and tattoos.

Q: There are things in your opera that are fictional. For example, Kitty Oppenheimer is portrayed as the embodiment of the feminine principle, but Kitty was not like that at all. She was not a good mother; she left Oppenheimer; she ferociously wanted the project to succeed.

A: The real Nixon is to the operatic Nixon as the real Julius Caesar was to Shakespeare’s version. We’re working in the poetic realm. Moreover, I don’t agree with you about Kitty Oppenheimer. According to American Prometheus [Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography of Robert Oppenheimer], she was incredibly unhappy at Los Alamos. She was a scientist relegated to faculty-wife status. Anyway, I don’t see why a person who has character flaws can’t have profound human and moral feelings about war.

Q: The Kitty material is presented too densely for my taste.

A: I, too, have some difficulties with Muriel Rukeyser [the poet whose words appeared in the libretto during Kitty’s parts]. Poetry is unknowable—each of us brings to it our own personal experience. As for density, check out Othello. Works of art can be dense. It could be that over time people find that density to be something they can really chew on.

Q: Why did you repeat text in the sonnet? It’s not a sonnet anymore.

A: Your ear is tuned to prosody, mine to harmonic necessity. Even the Beatles say “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah.” The “yeah, yeah, yeah” there is to confirm the phrase. What I don’t like to do is melisma. It’s a great tradition in opera; it just doesn’t suit me as an American.

Q: Is there any subject you feel is prohibited in opera? What student idea would make you feel compelled to say, “This wouldn’t work”? What would you feel profoundly uncomfortable treating operatically?

A: If I say nothing, I’m immoral. If I say something, then I’m stuck. Next question!

Q: What are your bulwarks?

A: Sterility is the greatest danger. The theme of Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus is sterility. Popular culture is a bulwark against that sterility. Rap. Stravinsky’s imagined primitive dance forms. Bartok’s hummus of Hungarian sounds. . . . There is raw, uncooked life force in popular culture.

* [There doesn’t have to be a connection to The New Yorker for us to run a report of this quality, but for those who crave one, Adams wrote of his early days as a composer in avant-garde Berkeley and San Francisco for the August 28, 2008, issue, and Doctor Atomic was reviewed by Alex Ross on October 27, 2008. —MCS]

Tonight at the Maison Française: More Appetizing Restaurant History, With Fresh Balzac

At least online, there are no longer tickets available to tonight’s New York Public Library discussion of William Grimes’s Appetite City, with Grimes, Ruth Reichl and Dan Barber. But for another, free angle on restaurant history, NYU’s Maison Française is hosting “Balzac, Restaurants, and Gastronomy,” with author Anka Muhlstein and Olivier Muller, chef de cuisine at DB Bistro Moderne (7:00 pm; via the discreetly indispensable Platform for Pedagogy).

Sempé Fi: Pigheaded This Way

_Pollux writes_:

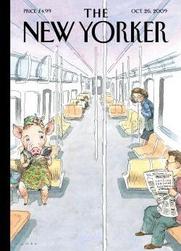

I’m feeling under the weather as I write this, and not because I so intensely dislike “John Cuneo’s”:http://www.johncuneo.com/ cover for the October 26, 2009 that it’s produced a negatively physical reaction in me, but because it’s flu season.

Perhaps it was inevitable that I should come across a virus one of these days. It waited for me in some dark alleyway or on some dirty doorknob. It eagerly waited for me with a set of sickness-carrying brass knuckles, and laid me low.

Cuneo’s subway passengers may also soon fall prey to sickness. They look alarmingly upon a very literal depiction of the swine flu. The porcine predator is putting on a disguise, ready to pucker up and deliver its insalubrious smooch upon unsuspecting victims. She wears old-fashioned clothes, but who can deny her present-day power?

The disguise isn’t a very good one. As the saying goes, you can put lipstick on a pig, but it would still be a pig. This was a “saying”:http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1840392,00.html#ixzz0VwUsQZ4c that of course achieved attention during the 2008 election and is the kind of folksy phrasing that politicians love to throw around and against their opponents.

Here Cuneo uses it as a link between the virus’ name and the fears and confusion surrounding it. No matter how many people shrug off the virus or the associated vaccine as a mere scare or scam, it remains among us. Denial is the lipstick that graces the unlovely lips of a pig.

Cuneo’s cover, called “Flu Season,” captures the fear and confusion that surround this flu season in which we have to contend with the ordinary flu and the swine flu. The H1N1 virus goes forth, claiming new victims, and at the same time a debate rages over whether people should take the vaccine or not.

“I am not going to take it,” Rush Limbaugh said, in an “address “:http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/booster_shots/2009/10/the-folks-who-publicly-said-they-would-rather-see-the-us-go-down-the-toilet-in-the-current-recession-rather-than-see-a-demo.html to Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius, “precisely because you are now telling me I must….I don’t want to take your vaccine. I don’t get flu shots.” Glenn Beck and Bill Maher, on opposite sides of the political spectrum, are also vocal in their skepticism of the vaccine.

As an _LA Times_ piece “commented”:http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/booster_shots/2009/10/the-folks-who-publicly-said-they-would-rather-see-the-us-go-down-the-toilet-in-the-current-recession-rather-than-see-a-demo.html, “this is not a liberal versus conservative issue. This is a science versus nonsense issue.”

Cuneo’s style reminds me of Barry Blitt’s in its mixture of inky lines and intentionally messy pools of paint. Cuneo, rendering the subway car in pen, inkwash, and watercolor, renders the subway car as a long, squiggly, scary hallway evocative of a hospital corridor.

The subway car is nearly empty; the cover’s central focus isn’t so much on the porker smeared with Lipfinity as on the desolate subway itself.

A female commuter steps on the subway car, uncertainly. She still has a chance to escape the virus. In the distance, a lone man quakes as he also looks up from a newspaper.

The pig looks seductively upon a man who reads a paper that announces the arrival of the flu vaccine. The pig has a “Come hither” look that would make the cover not out of place in Cuneo’s “_nEuROTIC_”:http://www.fantagraphics.com/index.php?option=com_virtuemart&page=shop.browse&category_id=417&Itemid=62, a recently published collection of erotic and hilariously perverse drawings.

The cover would be humorous if the prospect of getting sick were not so frightening. As another folksy saying goes, “sickness comes in haste and goes at leisure.”