Inspired by Obama’s win, I checked the index of the Complete New Yorker for items in the “Fiction” category that contained the word “president.” I got 167 hits, and I’ve been happily reading ever since. This is the second of a series on the results. The first one is here.

When the big credit crunch came to a head this fall, you might have heard occasional mention of the other bailout, that of the savings and loans in the late 1980s. If you want a brief, totally inaccurate primer on that event, you can do no better than Garrison Keillor’s “How the Savings and Loans Were Saved.” (Digital Edition link here.)

Huns invade Chicago, and President Bush (the First) nearly fails to act, with no political consequences: “… a major American city was in the hands of rapacious brutes, but, on the other hand, exit polling at shopping malls showed that people thought he was handling it O.K.”

Throughout, Keillor lampoons the terms that must have been used in the press to describe Bush’s lack of response: e.g., he appears “concerned but relaxed and definitely chins-up and in charge”, or he appears “burdened but still strong, upbeat but not glib … confident and in charge but not beleaguered or vulnerable or damp under the arms, the way Jimmy Carter was.”

Bush is always vacationing: playing badminton in Aspen, croquet at the White House, tennis and fishing in Kennebunkport. Meanwhile, the barbarians

made their squalid camps in the streets and took over the savings-and-loan offices,” where “they broke out all the windows and covered them with sheepskins, they squatted in the offices around campfires built from teak and mahogany desks and armoires, eating half-cooked collie haunches and platters of cat brains and drinking gallons of after-shave.

They demand a ransom of “three chests of gold and silver, six thousand silk garments, miscellaneous mirrors and skins and beads, three thousand pounds of oregano, and a hundred and sixty-six billion dollars in cash.”

Eventually, of course, Bush agrees to their primary demand.

The President decided not to interfere with the takeover attempts in the savings-and-loan industry and to pay the hundred and sixty-six billion dollars, not as a ransom of any type but as ordinary government support, plain and simple, absolutely nothing irregular about it, and the Huns and the Vandals rode away, carrying their treasure with them …

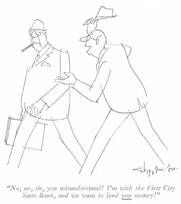

Absolutely no similarity, there, of course, to the credit crisis … or is there? This Robert Weber cartoon, from the July 18, 1983 issue (a few years, granted, before the S&Ls began to fail) sure sounds familiar:

What’s more, this Weber cartoon from the February 22, 1988 issue weirdly presages the crazed loan practices typical of the mortgage industry up until a few months ago.

But in the austere light of the credit crisis, perhaps you’ll find this Vahan Shirvanian cartoon from the May 17, 1969 issue a comforting reminder of better times: