Emily Gordon writes:

A few stars–and we don’t mean asterisks–are emerging in our punctuation-addressing contest to win Ben Greenman’s new book, What He’s Poised to Do. Here are the rankings of letter recipients so far, out of 82 entries and counting. What does this say about these marks, or about us as a society? We don’t know. All we know is, some of these little symbols are coming home with an armful of valentines (and a little hate mail), and some are Charlie Brown, weeping into their sandwiches. If you’re for the underdog, as we generally are, take a moment to send a note to, say, the solitary slash, or, for that matter, the ubiquitous but apparently invisible backslash. Send a salami to your manicule in the army! Keep those cards and letters coming.

The current rankings (to be updated frequently for those placing bets):

Ellipsis: 10

Semicolon (which has withstood some harsh attacks in the past): 8

Apostrophe: 7

Exclamation Point: 7

At sign: 3

Ampersand: 3

Asterisk: 3

Colon: 3

Parentheses: 3

Period: 5

em dash: 2

Grawlix: 2

Interrobang: 2

Manicule: 2

Question Mark: 2

Tilde: 2

Tied with one piece of fan (or unfan) mail each: acute accent, air quote, at-the-price-of, bracket, bullet, comma, curly quote, diaeresis, dollar sign en dash, exclaquestion mark, hyphen, interpunct, interroverti (formerly the inverted question mark), macron, percent sign, pilcrow, pound sign, quotation mark, smart quote, underline, Oxford comma.

No postcards, no wedding invitations, no junk mail, no J. Crew catalogue, no nuthin’: backslash, bullet, caret, copyright symbol, dagger, dash ditto mark, degree, ditto mark, double hyphen, inverted exclamation point, guillemets, lozenge, number sign (number sign! that’s the hashtag you use so shamelessly!), the “therefore” and “because” signs, slash, solidus, and tie.

Here are some stark and potentially upsetting images of those characters who have received no mail. Can you look into their fragile strokes and deny them the notice they crave?

\ • © ^ ° †‡ « » ï¼ ã€ƒ †◊ ∴ ∵ ¡ # / â„

Note: We realize that some of these marks are really less punctuation than they are typographical elements. But since they’re getting letters, or we think they should, we’re including them.

Category Archives: New Yorker

So You Love Punctuation? Write a Letter to Your Favorite Mark, and You Might Win a Copy of Ben Greenman’s Brand-New Book!

Update: We’ve announced the finalists, and the winner!

We loved every single letter to every single mark. Thank you!

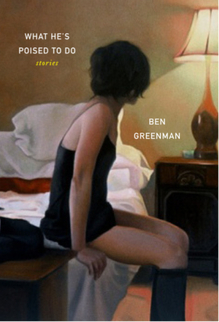

Ben Greenman‘s new book, What He’s Poised to Do, was recently published by Harper Perennial, and critics are already hailing its mix of emotional sophistication and formal innovation. Just the tip of the iceberg: Steve Almond, writing in the Los Angeles Times, calls the fourteen stories in the collection “astonishing,” and Pauls Toutonghi at Bookslut calls them “beautiful”–even better, “a book so beautiful, you’ll feel mysteriously compelled to mail it to a stranger.”

The book, in large part, deals with letters: how they are (or aren’t) effective conveyances for emotional intimacy and truth. Along with the book, Mr. Greenman has launched a site called Letters With Character, which invites readers to write letters to their favorite fictional characters–most recently, Alyosha Karamazov, Madame Psychosis from Infinite Jest, and Ernest Hemingway’s Yogi Johnson from The Torrents of Spring.

Here at Emdashes, we love letters (especially those sent through the postal mail), but there’s something we love even more: punctuation. Indeed, when we discovered that the upside-down question mark–as in ¿Qué?–had no official name, we challenged you, our readers, to rename it, and now the frequent (you wouldn’t believe how frequent) googlers who seek this information know the answer: it is the interroverti, all thanks to you.

In the same spirit, we’re combining two of our top-ten passions in life and challenging you to write a letter to your favorite punctuation mark, or perhaps one you find elusive, insufficiently loved, or sound but overexposed. Tell it anything you want: your fears, your frustrations, your innermost desires. Then put it in the comments section below so we can read it, too. Deadline: August 16. (We know all too well that it can take a bit of time to write a good letter–or even a telegraphic telegram.)

Here is a partial list of possible correspondents, with the current tally of blushing recipients marked in bold, and also ranked here in descending order of popularity: the acute accent, the air quote, the ampersand (3), the apostrophe (7), the asterisk (2), the at-the-price-of, the at sign (3), the backslash, the bracket, the bullet, the caret, the colon (3), the comma, the curly quote, the dagger, the dash ditto mark, the diaeresis, the dollar sign, the double hyphen (which is perhaps not what you thought it was), the ellipsis (10), the em dash (2)–toward which some jurors are slightly biased–or the en dash, the newly coined exclaquestion mark, the exclamation point (7), the full stop (2), the grawlix (2), the hyphen, the interpunct, the interrobang (2), the inverted exclamation point, the interroverti (formerly the inverted question mark), the little star, the macron, the manicule (2), the number sign, the parenthesis (((3))), the percent sign, the period (3), the pilcrow, the pound sign, the question mark (3), the quotation mark (or a pair of them), the controversial semicolon (7), the smart quote, the slash, the tilde (2), the underline, the Oxford comma, or any other mark close to your heart but not listed here. We will select the best letter and award the writer a signed copy of Mr. Greenman’s book, which may in fact contain the beloved mark in question. He may even add an extra one just for you.

Remember: Post your letter in the comments below by August 16, and you’ll be entered to win a signed copy of this exceptionally satisfying book of stories by one of our favorite writers. The best of the entry letters will all be collected in a post of their own, with sparkles, blue ribbons, and plenty of punctuation. If you can’t wait till mid-August to find out if you’ve won, and/or have friends who love letters and will love this book, of course, you can also order a copy.

Posting tip: You can use basic HTML tags to make line spaces; try the paragraph and break tags, as needed. If you don’t know how or would like our help, we are obsessive editor types and are happy to right the spacing for you.

Art note: The painting on the book cover is by Alyssa Monks, whose portraits of women and men and bodies and children and water and funny faces are scorchingly beautiful.

Factual note: We realize that some of these marks are really less punctuation than they are typographical elements. But since they’re getting letters, or we think they should, we’re including them.

Related posts and links:

Short Imagined Monologues: I Am the Period at the End of This Paragraph. [Ben Greenman, McSweeney’s]

Exciting Emdashes Contest! ¿What Should We Call the Upside-Down Question Mark?

Our in-depth coverage of punctuation–five years and counting!

More Emdashes contests, giveaways, and assorted bunk

Is That an Emoticon in 1862? [NYT/City Room]

Katha Pollitt, Roman Polanski, George Orwell, and Saul Steinberg Updated

Martin Schneider writes:

POE (pal of Emdashes) Katha Pollitt skewers the misguided Roman Polanski apologists.

It’s funny: I suspect that at FOX News headquarters the defenses of Polanski are an instance of the moral relativism of the Left. I’m a liberal, and most of my friends are liberals, and I have never spoken to anyone who seriously entertained the notion that Polanski shouldn’t be incarcerated, and here is one of the leading figures on the Left, ridiculing the idea that Polanski’s masterpieces give him a free pass on rape. Last year I was at a dinner party with about ten Viennese journalists, the very picture of decadent “European” elite, and everyone present agreed that Polanski was guilty and should be sent to jail.

So I don’t know who, exactly, is really defending Polanski. I wouldn’t be surprised if the set of people who defend Polanski consists mostly of cultural elite types; the point is that it’s a small group and that most liberals don’t hold this view. Can someone generate a Venn diagram for me?

Pollitt’s essay reminded me of George Orwell’s “Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali,” I was a big Orwell addict in the early 1990s, and I’m still a big fan, but what’s striking about the essay is Orwell’s cultural conservatism. Then again, it was 1944, pre-John Waters, pre-camp, pre-Lots of Things.

On the subject of Polanski: I should stress that I don’t dismiss his post-exile works. I’m a big fan of Frantic, and I thought Bitter Moon was terrific, and I liked Death and the Maiden a good deal too. (I haven’t seen The Pianist.) Polanski’s an extremely talented fellow. And he should be sent to prison.

Unrelatedly: some wag has updated Saul Steinberg’s famous map “View of the World From Ninth Avenue” (actually, it’s possible that its creator has never heard of Steinberg). What I don’t get about the update: What, exactly, is inaccurate about it? It looks just like a standard U.S. map to me.

Oh, one last thing: hail the jumper colon! I’ve sprinkled a few in this very post!

Ben Greenman Reads in Brooklyn on Monday 6/21 and It Will be Awesome

Martin Schneider writes:

Get on over to Brooklyn’s Greenlight Bookstore at 686 Fulton Street (at S. Portland, in Fort Greene) this coming Monday, June 21, at 7:30 pm, when Ben Greenman will read from his new epistolatory story collection What He’s Poised To Do, published by Harper Perennial. It’s a Facebook event, too, which makes it even easier to remember to move it to the top of your queue. We’re just about to launch a fun giveaway for Greenman’s book later this afternoon, so watch for that!

From the Facebook description:

The author Ben Greenman celebrates the publication of his new collection of stories, “What He’s Poised To Do” (Harper Perennial) and its sister blog, Letters With Character. There will also be brief readings by Jonny Diamond (of The L Magazine); the actress and performance artist Okwui Okpokwasili (representing Significant Objects); Nicki Pombier Berger (representing Underwater New York); and Todd Zuniga (representing Opium Magazine, and appearing via Transatlantic technology).

I don’t know the witty New Yorker writer and editor personally, but I’ve had the pleasure of attending a few New Yorker Festival events that he moderated (one was with Ian Hunter and Graham Parker, another was with Yo La Tengo; there were others), and he always made an extremely positive impression on me—intelligent, funny, generous, self-deprecating, all the good things. Emily tells me that based on her having gotten to meet him in person at a recent Happy Ending event, my impressions are rock-solid.

I’m in the wrong city (Cleveland) at the moment to attend this event, but New Yorkers should get right on this.

Stop Being So “Smug,” Imaginary New Yorkers!

Martin Schneider writes:

Recently Ezra Klein, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Conor Friedersdorf, and Andrew Sullivan have been blogging about New York City’s overweening cultural clout and—interesting, this—the tendency of its residents to behave in a smug manner.

I must say, the discussion has been extremely disappointing, and I came away from it feeling frustrated, annoyed, and not a little insulted. I guess it is helpful to find out how much people dislike you for reasons that seem insufficient or inaccurate. Such is the power of cultural envy, or something like cultural envy.

The discussion proceeded along the following lines: Friedersdorf wrote about New York’s worrisome centrality in all cultural matters and its pernicious effects on other major cities. Sullivan weighed in, agreeing and complaining about how “irritating” New Yorkers’ “narcissism” is. Accepting New Yorkers’ smugness as a given, Coates then wrote a fairly empathetic post in which he gamely tried to put that smugness in context. Then Ezra Klein (this was my entry point into the discussion) quoted Coates approvingly and called the behavior of New Yorkers “unseemly.”

As a lifelong New Yorker, all I can say is: WTF?

Notice how quickly the discussion devolved: in short order, it went from a look at the unfortunate tendency of New York to “hog” (my word) the major cultural and literary outlets to complaints about the self-obsessed behavior of New Yorkers. Quite literally, the discussion went from “It’s too bad that smart people in Phoenix and Houston and Denver don’t get a chance to have the literary spotlight” to “Yes; I’d never want to live in New York; the city is overrated and the people are narcissistic” to “Well, yes, but the people there are smug for a reason” to “New Yorkers are unseemly because they won’t shut up about how great their city is.”

That, my friends, is some serious devolution. In no time, the subject of the relationship of, say, The New Yorker (the magazine) to the literary scene in Denver (this is an interesting subject) was dropped completely in favor of an attack on unnamed New Yorkers for unspecified actions. In three posts focusing on the inability of New Yorkers to shut up about how great New York is, you know how many beastly New Yorkers were quoted or referenced doing this?

The answer, you may be surprised to learn, is zero.

That’s right: confronted with presumably countless examples of snobbish New Yorkers disparaging Indianapolis, Tulsa, Atlanta, or Baltimore, Klein, Coates, and Sullivan couldn’t be bothered to name a single instance of anybody doing this. In this discussion, that was taken as a given, just as in a book you don’t have to cite anyone to establish that Amsterdam is north of Rome. It is a truth just as self-evident, apparently.

This gets all the more astonishing if you contemplate analogous scenarios. Imagine if any of these men had endeavored to make some point about, say, Mexican-Americans in the same manner. Ahh, “Mexican-Americans are fine people and work hard, but they obsess too much about soccer and they have no interest in education,” let’s say. Do you think any of them would venture such a statement without casting about for some empirical evidence that what they were saying is true? Even a single anecdote? I doubt it. But apparently New Yorkers are not accorded the same courtesy. Such are the pleasures of living in America’s cultural capital or whatever.

I’m going to push back on this “self-evident” premise. Before I get to that, I want to make it clear that I do agree that certain New Yorkers, and I’ll even include myself in this group, are capable of some insensitivity on the question of the cultural offerings available in New York in comparison to those available in other parts of the country. There’s something to that, and saying so is basically fine. What I mainly question here is the use of the words “narcissicism” and “smug.” If the exact same discussion had been about New Yorkers’ “sense of entitlement,” I might not take much issue.

Let’s start with Klein’s post. Klein basically says that you can’t get New Yorkers to shut up about how great New York City is. Let’s quote:

About the worst thing that can happen to you in life is to be in a room with two Texans who start trying to tell you about the Alamo. Or about Texas. Or about how Texas was affected by the Alamo. But there’s something endearing about it, too. Texans are battling stereotypes that don’t tend to favor them. It’s like talking up your mom’s meatloaf. New Yorkers, by contrast, have what’s considered the greatest city in the country and can’t stop talking about it. It’s like an A-student bragging about his grades, or a rich guy making everybody look at his car. It’s unseemly.

So, from Sullivan’s “narcissism” we quickly get to Klein’s picture of New Yorkers incessantly talking up their city. Many of the people reading this are New Yorkers. I ask you, New Yorkers: Does this portrayal seem accurate to you? I may be completely blinkered, but it does not seem accurate to me. If anything, New Yorkers tend to betray an unspoken assumption that New York is superior and are less prone to acting evangelical about touting the city. Am I wrong about this?

Let’s talk about New York for a moment. Coates, to his credit, mentions the sheer size of New York City (he says that it’s “like ten Detroits”) and points out that, statistically speaking, you’re going to get a good number of boors in a population that large, no matter what you do. He refers to New York City as “what happens when you slam millions of people who are really different into close proximity.” Right on.

So given that, let me ask: Are taxi drivers from Ghana “smug”? Are the Pakistani owners of bodegas a “narcissistic” bunch? Who are we talking about here, exactly? When Sullivan and Klein talk about narcissism and smugness, aren’t they really talking about educated New Yorkers who work in publishing and similar fields? Does that make a difference? If they’re more “entitled,” is it still fair to make such sweeping generalizations about them?

To get a little personal here: Last week I spent a couple of days in South Carolina with extended family; the group was about 20 people, most of whom were raised in South Carolina or Georgia. Smart people; nice people. The entire time I was with them, at no point did I gush about this great museum exhibition or that awesome indie rock gig; it wouldn’t occur to me to do that, because it would obviously be rude and seek to put the others present at some sort of disadvantage. Also, it’s unclear how interested any of these people would be in a band they had never heard of or an exhibition they would have no opportunity to attend. It’s equally unclear to me how many New Yorkers would prattle on about the city in this manner. It seems to me, not so many.

We didn’t spend all that much time watching television, but some of us did catch the tail end of VH1’s Top 100 Songs of the 1990s and Betty White on Saturday Night Live. Both shows made for good communal watching experiences because we all had the same cultural purchase on the material. Everyone below a certain age was familiar with Nirvana, and we all could enjoy the punchlines involving the potty-mouthed Ms. White. And that was great; there was no potential for anybody to feel left out.

Another story: twice this year I drove out to Cleveland to witness a particularly memorable indie rock project called the Lottery League. (By all means, click and be amazed.) I met a lot of grand people during both trips, and I enjoyed it so much that I’m currently seeking to relocate there for the summer and maybe beyond.

Most Clevelanders are pretty wary of New York, for reasons I find perfectly comprehensible. A microcosm of that view can be found in the relationship between the “have” Yankees and the “have-not” Indians. It’s little wonder that Clevelanders (along with pretty much everyone else in the country) are sick and tired of the successes of the Yankees and that they refer to the team as the “evil empire.” (Given that, it would be a disappointment of epic proportions if LeBron James ends up abandoning his native Ohio for Madison Square Garden. I really hope he stays in Cleveland.) The Yankees serve as a symbol for everything New York has and other places don’t, and people hate New York for that.

It’s an accident of history that New York City is what it is, and yes, New Yorkers cherish it, you’re damn right we do. We are sometimes unthinking about assuming that another place might have, I don’t know, good theater, and we sometimes have to catch ourselves mid-sentence to avoid appearing rude. We do take that sort of thing for granted, yes. One name for that is “living in a place.”

It’s useless to deny that New York City tends to hog the attention-getting people and events that make a difference in the cultural arena. When you interact with outsiders about it, you can choose to pretend that it isn’t true (“Oh, I’m sure Indianapolis has great theater too!”), or you can disparage other places (“God, I could never live in Denver, there probably isn’t a decent restaurant in the whole city.”), or you can honor the reality in a relatively humble way (“Wellllll, you know New York, we’re all a little fussy about theater and the like, but it sure is gorgeous here on this South Carolina beach….”). Does that last one count as smug or narcissistic? I’m genuinely curious.

The fact is, New York City is a very specialized ecosystem, and its natives don’t always thrive outside that particular rainforest. This is a well-known phenomenon, isn’t it? The New Yorker who can’t leave the city, even though part of him hates it? We’re all a little misshapen.

So maybe a little compassion for us “smug” New Yorkers. As far as I know, anyone who envies the city is free to drive on over and move in, we’re very welcoming that way. And since we’re accustomed to teeming multiplicity in all its forms, we’re a little slower to describe vast groups of people with a single disparaging adjective without any kind of evidentiary backup. It’s kind of a local tradition ’round these parts.

Some Quick Hits on a Recent Issue

Martin Schneider writes:

I’m finding the April 26 issue of The New Yorker (green cover) kind of delightful. In no particular order:

1. Hendrik Hertzberg’s Comment is excellent and also clarifies a subject that I’d pretty much missed, President Obama’s recent successes on the nuclear proliferation front. If you think you might have missed it too, do check it out.

1a. Hertzberg quotes Obama’s “Dmitri, we agreed” comment to Medvedev that apparently sealed the deal in the end.

The line possesses … an odd echo* of some of the most delicious dialogue in Dr. Strangelove, which movie Hertzberg cites in the beginning of the Comment, when President Merkin Muffley, played by Peter Sellers, is on the phone to the Russian premier to tell him that the United States is about to destroy the USSR for no good reason:

Well let me finish, Dimitri. Let me finish, Dimitri. Well, listen, how do you think I feel about it? Can you imagine how I feel about it, Dimitri? Why do you think I’m calling you? Just to say hello? Of course I like to speak to you. Of course I like to say hello. Not now, but any time, Dimitri. I’m just calling up to tell you something terrible has happened. It’s a friendly call. Of course it’s a friendly call. Listen, if it wasn’t friendly, … you probably wouldn’t have even got it.

So, so good.

The other thing that struck me about “Dmitri, we agreed” is that it may be the most quintessentially Obamanian statement of any importance he has ever uttered as president. That statement is wholly consistent with the person I supported as early as 2007, voted for in 2008, and haven’t seen quite enough of since.

2. Dana Goodyear’s article on the restaurant Animal in Los Angeles (not available online) is a sheer delight, and towards the end takes on an almost fictive quality. A great subject, and she did the most with it.

3. The letter Saul Bellow wrote to Philip Roth on January 7, 1984 (not available online), is pretty fantastic, even if his appellation for the poor journo who crossed him, “crooked little slut,” is a bit unfortunate.

4. Billy Kimball’s list of rarely heard complaints about the iPad is very funny.

===

* Update: Somehow I missed that Hertzberg quoted a different part of Muffley’s telephone monologue to start off his Comment. Kudos to Hertzberg for spotting this echo long before I did.

Not Interested in Seeing Pavement, Thank You

Martin Schneider writes:

By now, everyone who cares knows that Pavement has reunited and is touring. They’ve got several dates at Central Park in September, tickets to which cost Lord knows how much, and they’re playing some festivals, including Coachella and Pitchfork. So far, the word is positive: the band sounds good and they’re motivated (always a problem with Pavement).

I belonged to the original cadre of Pavement geeks. I fell for them hard in 1993, when I first heard their first album Slanted and Enchanted, and I bought everything they released until they broke up. Pavement was my first serious musical obsession as an adult, and for many years they were the band that most defined my taste and outlook. I was really into them. Still am. They’re a great band.

I saw them four times in the 1990s, and those shows were mostly transcendent experiences, the kind of shows that only happen when a true favorite is performing, the kind of shows you look forward to for weeks.

The question arises: should I see Pavement a decade after their original incarnation? I’m certainly tempted, but … what exactly would I be getting out of it? I still love the tunes and the players remain likable and the general group exultation of the event would certainly be fun. A friend who runs a prominent mp3 blog was telling me recently that Pavement is much, much bigger now than they ever were when they were still putting out albums, and to experience that level of public approbation (finally) would be a fine thing.

But—on the other hand, I did experience them the first time around, and it’s a little unclear what I, as an original Pavement obsessive, stand to get out of the deal. The tickets are pricey, and I don’t exactly have to validate my fandom; that already happened long ago. I never saw the Pixies, but if I were to see them today, my incentive would be to see a legendary band I never got to see. I don’t have to do that with Pavement.

You may find these musings neurotic or almost enjoyment-averse. I understand that reaction, and yet the basic conflict remains. I’m not averse to aesthetic or cultural pleasure in the least, as any of my friends will attest with alacrity. I’m just confused what I’d be getting if I pay to see Pavement play their back catalog in 2010.

Be that as it may. To this quandary, add a truly perplexing article by Jon Dolan in the latest issue of SPIN, which also happens to be the 25th anniversary issue. I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to say that this article makes the best possible case for staying away from these Pavement shows. It left such a bad taste in my mouth that I think it made my mind up for me.

Since Pavement is so doggedly … deconstructionist, for want of a better word, Dolan adopts a strategy (“Pavement always made a certain realism a centerpiece of their appeal,” after all) of addressing the monetary factor involved in Pavement’s decision to reunite, to a degree that is a little bit nauseating. Quotation is my friend:

You become a rock star when you can get onstage without adding anything new to your artistic legacy and still make thousands of people lose their minds. It’s adulation as ritual, expectations met as a matter of course.

…

Yet, despite singer-guitarist Stephen Malkmus’ semi-pooched voice (he’d been fighting off a cold), Pavement were the same pretty-decent live band they were 15 years ago — sorta distant, kinda ramshackle — plowing through a catalog that feels as obliquely poignant as ever.

…

The economics of what Malkmus calls “these nostalgia things” has long been formalized, as every one from the Pixies to Polvo comes back to cash in on legends that have ballooned in the band’s absence, as oldsters entreat youngsters to do their history homework. Provided a band can go through the paces without dredging up any old grudges or hurting themselves, the offers get pretty hard to refuse.

“If the band likes hearing people cheer, and getting a check, as is the case with us,” says Malkmus, “then it usually ends up working out, even if they’re just ham-and-egging out the same old chords.”

After five years on the reunion circuit, the Pixies’ Black Francis recently came out with the maxim for the moment: “Forget the fucking goddamn art. Now it’s time to talk about the money.” (Let’s: A New York-based booking agent estimates that indie bands that were lucky to pocket $7,000 a night in the mid-’90s can now command mid-six figures for a single festival date and low-six figures for one show at a large theater.)

The 43-year-old Malkmus is acutely aware of what he calls the “dialectical materialism” of these events, but for him, grandstanding like Francis’ seems redundant: “If you’re 40, and you leave your family and fly to Australia to do shows, and you’re doing it for the art, that seems kind of weird. If you’re doing it for the art, stay home with your family.”

Enough. It’s good to be told that there are no illusions here. I’m not expected to pay for “art” or even a good musical experience, although Dolan does sprinkle in some compliments between the references to Malkmus’s shot voice, their “pretty-decent” live chops, and their “plowing” through their old hits.

In the last paragraph Dolan writes, “There’s a deeper realism at work here. … With the global economy in the toilet, the ambivalence toward capitalism that Pavement exemplified seems like an outmoded luxury. In 2010, indie-rock fans should take some solace that there are still paychecks for nostalgia acts that only had theoretical hits.”

Lucky me! I helped Pavement become the eccentric indie heroes in their original stint—I’m talking hard cash here—now it’s my turn to be part of their grassroots 401(k) plan too! Gosh, it’s good I can take some solace that Pavement can still calculatedly fleece their newer fans and provide an authentic veneer of credibility—yes, the contradiction inherent in that phrase is intentional—even if most bands have a hard time making ends meet.

Why I should be supporting Pavement, and not those hard-up bands…. that part isn’t explained so clearly. I know I might come off as harsh and bitter; truly, I’m more annoyed or fatigued than bitter. But more to the point, I don’t see why this reaction is wrong on the merits.

I’ll always root for Pavement on some level, and I’m delighted that they have found a new audience that was probably in diapers the first time around. That’s awesome, it’s a validation of my twentysomething instincts, and I’m glad their albums have a fair shot at lasting a good deal longer than the albums of most of their contemporaries. They’re great albums.

But the concerts? I’ll leave those to others to enjoy.

Remnick and Coates: Video

Martin Schneider writes:

A couple of weeks ago Emily, Jonathan, and I attended an event at the New York Public Library with David Remnick and Ta-Nehisi Coates. I wrote about it here. The New York Public Library has posted a video of the event here.

That event was pegged to the publication of Remnick’s new book about Barack Obama, The Bridge. In line with that fact, Remnick has recently appeared on The Daily Show and Real Time with Bill Maher. The Daily Show‘s website has video here; HBO, which airs Real Time, doesn’t let you see video for free, but a free audio podcast of all telecasts is available on iTunes.

In the Daily Show appearance, Remnick called Jon Stewart a “sweetie pie,” and Stewart confessed to an unhealthy obsession with The New Yorker‘s weekly caption contest. The two men briefly discussed Barry Blitt’s originally notorious and now merely legendary cover featuring Michelle and Barack Obama from July 2008. Remnick remarked that The Daily Show “saved our bacon” on that particular subject. It’s well worth checking out Stewart’s coverage of that furor, to recall both the truly ridiculous (and apparently unanimous) condemnations The New Yorker received from the cable news outlets and Stewart’s own bottomless sensibleness.

Can Adam Gopnik’s Maturity Countenance Chase Utley’s Glee?

Martin Schneider writes:

There’s been an interesting back and forth on the New Yorker blog pages about Adam Gopnik’s decision to forsake baseball. To recap: Gopnik announced that he no longer much likes baseball, Richard Brody and Ben McGrath responded, then Gopnik wrote again, and so forth. The exchange may not even be over. The best way to follow it all may be to go to the Sporting Scene section and read them in order.

All parties have been intelligent in their advocacy, and I write not so much to correct Brody and McGrath as to supplement them. I find Gopnik’s line of thinking not very convincing and even a bit disingenuous, and since I am a big baseball fan, I thought I would explain why.

Yesterday I attended the home opener for the Cleveland Indians in Progressive Park. The Rangers beat the Indians, 4 to 2, in 10 innings, alas. I was there with three friends, and we had a good time in our outfield seats. Along the way we discussed the unkillable “problem” of baseball losing popularity.

How shall I say this: unlike any endeavor I can think of, baseball is littered with testaments to why baseball is no longer what it once was and also attempts to understand why it will soon not be what it now is. That is to say, baseball fans are constantly telling you that baseball today sucks, and there are two possible offshoots to that premise: first, that the speaker is newly disenchanted (Gopnik); and second, that future generations may not sustain the passion for the sport that we are currently displaying.

I find such worries, to say the least, overdetermined. My position is, to put it bluntly, baseball is still a fine game, its problems are vastly overemphasized, and who really cares if you or some future generations don’t like it so much.

Baseball is incredibly popular. This is a fact. Millions of people attend the games, and millions of people watch the games on television. Millions of people play fantasy baseball (I do), and millions of people pay close attention to the pennant races, playoffs, and World Series. I heard it said on WFAN last week that the revenues for MLB recently passed those for the NFL for the first time in many years.

If this is failure, then I say, Three cheers for failure.

But even if there were serious flaws in the game that were to drastically diminish its popularity short of—I can’t believe I’m writing this phrase—threatening its existence, why should that bother anybody, really? I am not the Treasurer or Accountant for Major League Baseball, and if baseball were to suffer a profound decline in popularity/ratings/revenues of, say, 20 percent, I find it difficult to understand why this would affect me—since I would almost certainly still enjoy the game and derive pleasure from following it.

A hypothetical comes to mind. I am not a serious Star Wars fan. I was seven years old when the first one came out, I had a fairly normal childhood admiration over the first trilogy, and as an adult I’ve come to dislike the whole project quite a bit—yes, the whole thing. Call me the Gopnik of Star Wars, our positions here are probably pretty analogous.

Now, let’s say you, reading this, are a huge Star Wars nerd. What if I were to tell you that, for some imaginary reason, the 1977 gross receipts for Star Wars were, shall we say, 10 percent less impressive than anybody realized at the time? I would essentially be telling you that you have this picture in your mind that Star Wars had Impact X on our culture, and that you, if you were being scrupulous about the truth, would henceforth be forced to downgrade that Impact to something like 90 percent of what you had originally supposed.

Would you find this news distressing? I can certainly imagine that many people would be distressed by that news. The question I have is: Why? If you enjoyed the movie and its sequels as a child, and if you enjoy them today, I don’t really see what difference it makes that a few hundred thousand strangers did not like it as much as you had once thought. The whole concept is alien to me.

Baseball is not your favorite indie band that nobody you know has ever heard of. In that example, it’s sensible to root for the popularity of the project, because its very existence depends entirely on a spike in popularity. Baseball is not in that position.

When we raise the issue of pessimistic prospects for baseball, or investigate one individual’s decision to abandon the sport’s allures, that’s pretty much the situation we’re in. If baseball loses popularity in 2020, 2030, 2040 and there are still strong reasons for my interest to hold steady, I don’t really see what the fact of some unnamed demographic group deciding they like something else better has to do with me. It’s very likely that baseball will still be pretty popular in thirty years, and my desire to watch the World Series, no matter who is playing, will probably also remain. Similarly, I don’t really see why Adam Gopnik’s decision, at the age of 54 or so, to abandon what is after all a child’s game, should interest anybody, in and of itself.

Are we supposed to regard Gopnik’s decision as a canary in the coal mine? I think that is the unmistakable point of Gopnik’s first post, and let’s just say that I disagree with him that the post is actually serving that purpose in any meaningful way.

Having written “around” the problem of Gopnik’s manifesto for several paragraphs, let’s take a closer look at Gopnik’s first post. I don’t want to go through the argument or anything like that, but I did want to hit a couple of quick points.

Start with the opening line: “I am eager to become a baseball fan again.” Frankly, I don’t believe Gopnik when he writes this. The situation that baseball finds itself in is, in my opinion, not so dire that anybody genuinely wanting to love it would truly be barred from doing so. Furthermore, the statement is belied by the rest of what Gopnik writes, which smacks of rationalization, or, as McGrath puts it in the service of a slightly different point, “the use of the statistical record as a kind of moral ballast for what are essentially emotional arguments.”

Be that as it may. Let us now turn to the closing lines of Gopnik’s first post: “The dance of shared purpose and loyalty may be merely a mime—but what else but dancing and miming do we go to games for?”

I understand that it is unpleasantly bracing to realize that athletes are also businessmen, that the teams’ owners are not altruists, that fandom and commerce are intertwined. These are difficult things for an adult to accept about a fondness gained in childhood.

But I must ask: exactly how does Gopnik know that this “mime” is absent, or is being enacted to some insufficient degree? I have an image in my mind, from November of 2008, of a fellow—let us call him a “businessman”—named Chase Utley on a stage in the center of Philadelphia, proclaiming the Phillies the “World Fucking Champions,” to the cheers of many thousands of the city’s citizens.

I must say, his “mime,” which certainly seemed to express a level of jubilation over having won a championship, was a particularly shrewd bit of PR/mime/lying, that would probably have a positive impact on the portfolio of Chase Utley Inc.

But wait—could there be another explanation? Could it be that Utley meant it? Could it be that Utley was sincere in his joy? Is it actually possible that Utley takes pride not so much in his bank account but in his athletic prowess? That the kinship he felt with the other regulars of the “World Fucking Champion” 2008 Phillies was genuine? What if it wasn’t a mime at all?

Gopnik seems to rule out the possibility. Because if he did accept that premise, that Utley is first and foremost an athlete who desperately desires/desired a championship, and not first and foremost a businessman who coolly desires a robust array of assets, then I don’t see how he could have written what he did.

In 2007 I saw Gopnik on stage at the New Yorker Festival, debating with Malcolm Gladwell about the future of the Ivy League. I know from that experience that Gopnik has a subtle mind and can argue creatively and persuasively. For some reason, baseball has a singular tendency to cloud people’s ability to argue cogently. I look forward to a more tough-minded explanation for Gopnik’s new distaste for baseball and its relevance to baseball fans at large.

Report: Remnick and Coates, at the New York Public Library

Martin Schneider writes:

On Tuesday, April 6, I joined my Emdashes colleagues Emily Gordon and Jonathan Taylor at the New York Public Library for the publication day event for The Bridge, David Remnick’s eagerly awaited book about Barack Hussein Obama, the 44th President of the United States. It was an hour of spirited discussion about Obama, moderated by Atlantic Monthly blogger Ta-Nehisi Coates, who has written two articles for The New Yorker and also appeared as a panelist at the 2008 New Yorker Festival.

In the summer of 2008, Remnick and New Yorker executive editor Dorothy Wickenden entered into a wager about the election’s outcome—Remnick’s full explanation of his pessimism was a slow repetition of Obama’s full name. Today, as Remnick rightly says, nobody thinks much about that “Hussein.”

Remnick is so eloquent that I think we may have to invent a new word to describe him. Let me explain. When one listens to Remnick speak, he is so effortlessly precise and profound that one almost wants to use the word “glib”—but, of course, that word implies a want of substance, and nothing could be further from the truth. Is there a word for someone who appears to be glib but in fact is supplying all manner of valuable insight and even profundity? I don’t know, but we need one.

I’ve seen Remnick speak before, but always as the interviewer or moderator, never as the subject. Emily afterward pointed out how easily Remnick took to the role, comfortably reminiscing about his suburban New Jersey upbringing, in a household where radicalism was defined as “sitting too close to the TV set.” In short, a more personal Remnick.

The banter between Remnick and Coates was very amusing—much was made of their offstage editor-contributor relationship. For me, the funniest moment of all came during the Q&A section, when Paul Holdengräber,Director of Public Programs at the NYPL, asked Remnick about “that famous New Yorker cover,” obviously a reference to Barry Blitt’s “notorious” July 21, 2008, cover depicting Barack and Michelle Obama after having converted the Oval Office into a den of Islamist Black Power. Remnick: “The one with the bowl of fruit? The one with the abandoned summer house with the clothesline going across?”

Remnick’s take on the cover was, as always, astute: “I think it’s fair to say that not everybody liked it …. I was surprised at the scale of the not-everybody-liking-it.” It’s a lovely irony that Remnick, of all people, so convinced that the key to Obama’s undoing lay in his middle name, would be the editor to approve that cover. But of course, Remnick’s responsibility was not to ensure Obama’s election. And, in my view—as unpleasant as it must have been for Remnick to be hectored on live TV by the likes of Wolf Blitzer, who noted, with characteristic subtlety, “This could have been on the cover of a Nazi magazine!”—it was an entirely worthwhile gamble. (Remnick, for his part, drily noted that he hoped his mother was not watching CNN that particular day.)

To this day, Coates objects to the cover, on the grounds that the cover showed the right-wing conspiracists’ worst fears as “not ridiculous.” But of course, that is precisely what it did, it rendered them ridiculous. You couldn’t ponder that cover for very long without all of the scary right-wing premises seeming preposterous. I quote Art Spiegelman to that effect here, and contribute my own thoughts here. It may have been in a stealthy way, but Blitt’s cover, if anything, probably helped Obama just a little bit.

It’s impossible to discuss the meaning of President Obama without discussing race, and when the moderator is a black man who has written a memoir that would appear to be a bit similar to Obama’s own memoir, the subject of race is all the more unavoidable—and welcome. Remnick’s and Coates’s comments were unfailingly astute—but I did want to push back on one point that surprised me a bit.

Everyone has a theory about how Obama’s blackness helped him or hurt him. Obviously, Obama was able to maximize the ways it could help him and minimize the ways it could hurt him, the same way that Hillary Clinton would have tried to exploit/downplay her gender, or any other candidate would try to extract the positive aspects of any other notable trait he or she possesses.

But it remains a thorny subject. Our first “black president” is half-white, just as white as he is black, one might even say. Yet he signifies as black, culturally speaking, for reasons that stretch back to the abhorrent “one-drop rule” of slavery. Biracial Derek Jeter might not signify as “all black,” but in the more charged arena of politics, Obama usually does.

Add to this a subject that Remnick and Coates treated with some delicacy, that Obama’s father was not culturally African-American but simply African, which means that Obama had no obvious recourse to the cultural traditions and territory of regular African-American males, the ones descended from slaves. Obama is not a descendant of American slaves, and Remnick and Coates quite properly presented that as a problem for a candidate (Obama) trying to win the votes of African-Americans. You could almost say it could have been a problem along these lines: whites would disinclined to vote for him, since he signifies as “black”—but some black voters might also be (relatively) disinclined to vote for him—because he signifies to them as insufficiently “black.” Certainly that would have been a pickle.

Remnick and Coates were making the point that Michelle Obama sliced through this particular Gordian knot rather tidily. Michelle Obama, née Robinson, namesake of America’s most historic African-American baseball player.

So far, so good. Where Remnick and Coates lose me is their assertion that a hypothetical Obama with a white wife would have faced unusual—possibly fatal—problems. I should stress that I’m not shocked by that statement, and I’m not calling them on it for reasons having to do with political correctness. I’m just not sure the statement is as self-evidently true as the two men seemed to think.

Remnick’s statement was that Obama would not have secured 94% of the black vote if Obama’s wife had been white. Coates’s version, allowing for the usual ambiguity that occurs when people speak extemporaneously, seemed to bleed into the premise that Obama would not have won the election at all. Remnick’s statement is probably true in the narrow sense, if one adds the caveat that he could have secured 93% of the black vote and the statement would still remain true. As for Obama’s general prospects, it’s … a difficult statement to parse.

In some degree, this hypothetical seems to elevate cultural concerns over political ones. The fidelity of black voters to the Democratic Party is a political fact strong enough to trump a lot of other factors. It’s worth pointing out that in 2004, a white native of Massachusetts married to a white ketchup heiress (born in Africa, oddly enough) secured 88% of the black vote—and that was a low figure, in historical terms. And of course, Kerry lost the election. But are we saying that Obama would have done worse than Kerry? Are we saying that Obama’s political career would have stalled in Chicago because he would not have been able to appeal to “more authentically African-American voters” the same way? The counterfactuals are too involved to figure out, and—my real point—they ignore the salient role that the characteristics of specific human beings play.

Racially, Obama is whatever he is. In addition, he’s thoughtful, careful, eloquent, whip-smart, not prone to verbal gaffes … this is the man we are saying who could never have overcome his choice decades earlier to wed a white woman? I see the dynamic involved clearly enough … I just don’t think we can rule any outcome out so easily.

Predictions and hypothetical questions are bedeviled by recourse to average, typical exemplars. As an example, if you had asked a sportswriter, on May 30, 1982, whether any current major leaguer had a chance to break Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games streak, that sportswriter would very likely have said, “No. That is not possible.”

But of course Cal Ripken played the first game of his (quite a bit longer) streak that very day. Obviously the mental processes of that sportswriter would not have been up to imagining the possibility of a glorious outlier like Ripken—even though by definition that record would necessarily be broken by an outlier. Thinking about the ordinary major leaguers are of no use in answering a question like that.

Similarly, if we imagine this white woman that would supposedly have hindered Obama’s chances of becoming president, who is this woman, exactly? Or, more precisely, who might this woman be, exactly? Hillary Clinton? Cindy McCain? Teresa Heinz? Nancy Reagan? Nancy Pelosi? Barbara Ehrenreich? Sandra Bullock? Lorrie Moore? Even that short list of remarkable women shows the potential range involved.

Maybe I’m naive. Obama’s task was formidable enough as it was, and (as Remnick pointed out) his eventual path was in part the result of astonishing good fortune. Maybe it is true that Obama would never have gotten elected within Illinois, much less across the whole country, if he had not had an easy way to make regular black voters relate to him. But I tend to think of the issue in the following way.

Barack Obama married a remarkable woman. It’s safe to assume that if his chosen bride had been white, she would have been a pretty remarkable woman too. Her race might have complicated Obama’s political life. But alongside that, there are two other things one might venture as well: Obama excels at overcoming circumstances that would hold other people back, and this woman would have brought something to the project (I almost wrote “ticket”) in her own right.