Benjamin Chambers writes:

Emily says today is Emdashes’ fifth anniversary. In celebration, I offer the following cartoon by Claude Smith, from the June 24, 1967 issue of our favorite magazine. I like to think the group is looking at an early mock-up of this blog. (Click for larger view.)

P.S. You can also consider it an entry in Martin’s series of Mad Men Files columns.

Category Archives: New Yorker

David Levine, 1926-2009

Martin Schneider writes:

Some people, you figure they will just always be there. David Levine was drawing caricatures for The New York Review of Books well before my birth, and it was only reasonable to suppose he’d be at it years after my death, too. It’s difficult to imagine a world without a steady succession of new Levine drawings in it; it’s not merely perverse fancy to wonder whether Levine’s death makes it impossible for The New York Review of Books to keep publishing articles. That is how strong that association was.

You may have guessed that I grew up in a household with The New York Review of Books in it. Has there ever been a connection between an illustrator and a periodical as strong as that between Levine and The New York Review of Books? Norman Rockwell and The Saturday Evening Post, I guess. I can’t think of another one. His drawings meant as much to the identity of that journal as—if not more than—Rea Irvin’s typeface and monocled fop have meant to the image of The New Yorker.

How do these things happen? It’s not just that the drawings synecdochally came to represent the high quality of the articles in The New York Review of Books; the transferral of associations very nearly worked the other direction, too. I guess it’s just a long-winded way of saying, the artist and the periodical were made for each other.

Maybe the highest compliment one can pay Levine’s work (at least the caricatures; he was also a painter) is that the work lies in some realm beyond which the word “witty” really has no meaning. They were not “witty,” and they were not lacking in wit, either. Many of the drawings contain the kind of visual puns that constitute the most basic elements of the caricaturist’s trade. And the drawings could have dispensed with them altogether, without any loss of quality. The drawings rewarded the intelligent and informed reader who is in a mood to be serious but also engaged. In short, the New York Review of Books kind of reader.

Levine’s art appeared in The New Yorker many, many times, but it would be folly for me to celebrate him as a New Yorker contributor, impressive though those contributions surely were. It would be like celebrating Michael Jordan’s exploits for the Washington Wizards.

Earlier this year, I was obliged to empty out the house in which I grew up. Thirty-five years of living had accumulated in its corners, and I was forced to throw much of it away. During that process I came across a faded sheaf of twelve prints by Levine, presumably distributed to subscribers (in this case, my dad) a decade or three ago. I threw away so much, but I kept this, because reading means something to me, because ideas mean something to me, because The New York Review of Books means something to me, because David Levine means something to me. I’m looking at the prints as I write this.

Holy Last-Minute Gift, Der Fledermausmann!

Benjamin Chambers writes:

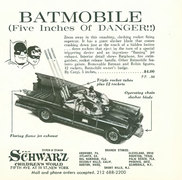

What would have been the perfect, last-minute gift for someone on your holiday shopping list in 1966?

I’m betting it would’ve been the Batmobile seen on p. 185 of the October 1, 1966 issue of The New Yorker. (Click on the image below for a larger view.)

I was lucky enough to own one of these (though I didn’t get it until 1971 or so), and I can attest that it was the coolest toy car ever made. I quickly lost the “rockets”, but nothing ever dulled the joy of the car’s sleek lines, the futuristic windshield, or the chain-snapping blade that would pop out of the hood.

Curious to see if the Batman ever showed up in The Complete New Yorker, I was pleased to see that he did. I’ll have more to say about this at another time, but my favorite find was the Everett Opie cartoon below, from the June 24, 1967 issue. (Again, click on the image for a larger view.)

Naturally, the cartoon made me want to look into the Strauss operetta, “Die Fledermaus,” which I’d heard of, but never seen. I was amused to learn from Wikipedia that the gist of the finale is, “Oh bat, oh bat, at last let thy victim escape!”

Priceless!

That Thunderbird Touch

_Benjamin Chambers writes_:

Cruising through The Complete New Yorker (TCNY) the other day—though without a unique Safety-convenience Panel—I ran across a great ad for the Ford Thunderbird on page 5 of the December 25, 1965 issue (click image for larger view):

It’s interesting how explicitly the advertisers (Mad Men, anyone?) tried to evoke the romance and cachet of flight: the sheer novelty of having an overhead, “Safety-convenience” instrument panel was used to connote the complexity of the cockpit, and the driver was shown wearing, of all things, a pilot’s uniform. Drive this car, in other words, and you will be captain of your destiny, far from earthly cares … Hard to imagine that idea resonating with anyone today who’s flown coach.

However, I was intrigued by two of the car’s new features: the Stereo-Sonic tape system, and the “automatic Highway Pilot speed control option.” Maybe I’m showing my age, but I had no idea what Stereo-Sonic tapes were, and was surprised to learn they were 8-Track tapes. I hadn’t realized they were introduced so early. (According to Wikipedia, Ford introduced 8-track players in most of its automobile lines in September 1965.)

The mention of the “Highway Pilot speed control option” made me wonder when cruise control was first introduced. Turns out it’s been around since the 1910s (!), though the modern version first appeared in a 1958 Chrysler.

Apparently, the guy who invented the modern version did so after he got tired of the way his employer kept speeding up and slowing down when he was talking as they drove along together. Who knew that highly-useful invention was born of such deep irritation? Maybe that’s why the driver shown in the ad has no passengers. Wouldn’t want to spoil the illusion of peaceful command by including insubordinates just itching to fix your wagon …

Challenge: Connect Random Stuff in My Head to the Magazine

Martin Schneider writes:

Oh boy, my favorite parlor game…. also called “How Emdashes generates posts.”

1. Last night I saw Jason Reitman’s movie Up in the Air, and I enjoyed it very much. It certainly did seem like a movie that teed up its subject perfectly and then whacked it, which I’m not sure is quite the same thing as being a great movie, but … I’m quibbling, it was very good. I’ve spent a lot of time in airports recently, so I had to see it before all that useless knowledge wore off.

Connection: The movie was based on a book by Walter Kirn, who had a story published in The New Yorker in 1997.

2. Lou Reed and Ben Syverson designed and programmed an iPhone app called Lou Zoom. I installed it on my iPod Touch. What does it do, you ask? Why, it takes your Contacts list and renders it in much larger type. This accomplishment does rank below revolutionizing American avant-garde rock and roll, but not many things are as monumental as that. Plus it has to be the coolest way ever to tell the world, “I’m OLD! I can’t read this small type anymore!” (And you know, I think the app is very good. I do prefer looking at it to the default Contacts app.)

Connection: The New Yorker published excerpts from Lou Reed’s tour diary in 1996.

3. Oh man, is this picture great:

Connection: The New Yorker hardly ever misuses apostrophes, making this sign the anti-New Yorker.

Platon Shoots Netanyahu, Qaddafi, Obama — and Many Other Potentates

Martin Schneider writes:

It was quite a spree.

My involvement with Emdashes recently has been minimal, but purely for logistical reasons. I’ve been traveling a tremendous amount and also was not getting the physical magazine shipped to me, and under such circumstances it becomes increasingly difficult to stay engaged with the magazine and feel as if one has anything worthwhile to say. Fortunately, the first problem (constant movement) is now solved, and the second (delivery of magazine) is being remedied even as I write this. I expect to be more engaged in the near future.

I did, however, want to take a moment to lavish praise on Platon’s recent gallery of world leaders. I saw it linked at Jason Kottke’s glorious weblog, and—well, I was really blown away by it. I can’t say that I’ve seen any work of Platon’s that struck me as anything less than excellent, but I don’t think I realized just how good the man is until I clicked on all forty-nine snapshots and listened to all forty-nine of his individual comments. If you haven’t done so, I urge you to spend a quarter-hour looking at the pictures with some care. The results are fairly astonishing.

The comments are about what you would expect—he generally praises everyone and then makes an observation about each subject’s personality and/or physiognomy and sometimes reflects on the circumstances of the meeting or the technical approach he chose for the subject. Most of the pictures are black-and-white facial portraits, but some are in color and some feature the subject’s body to some degree. I must say I found it quite impossible to question his judgment in almost any of the cases. They all seemed rather remarkably well done to me.

If Platon is the new Richard Avedon—am I the last person to figure this out?—then I must say The New Yorker made an excellent choice. I have made the transition from sympathetic observer to fan.

The Importance of Knowing What You’re Good At

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Reading some old hard-copy issues of The New Yorker dating from the 1990s, I ran across the “Postscript” piece by Lee Lorenz on George Price, from the January 30, 1995 issue.

I grew up with Price’s angular cartoons and his quirkily dry sense of humor— and since the guy did over 1,200 drawings for the magazine between 1929 and his death, many people alive today can say the same—so I was stunned to learn that “only one [of his cartoons], amazingly, was based on an idea of his own.”

What Price was good at was drawing, and so he used punchlines that were supplied for him. It wasn’t that uncommon to use gag writers, but I’d guess the frequency with which he did so was, and the way the results do seem to be so of-a-piece, as if the punchlines and the drawings really were the product of a single mind.

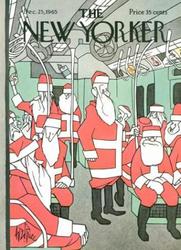

It’s telling, I think, that the one drawing that was based on his own idea was a sight gag, and didn’t have a punchline. It appeared on the cover of the December 25, 1965 issue, and can be seen below. (Click the link at left to find it on The Cartoon Bank; click on the image below to see a larger version.)

The same 1995 issue of TNY that contained the homage to Price also featured David Owen’s profile of software entrepreneur and art patron Peter Norton (Norton Utilities, anyone?). I read the profile at the time the issue came out, and for the past 15 years, it has stood out in my memory as an excellent portrait of a bright, highly unusual man. One of the amusing things in the piece:

Nerd tycoons differ from robber barons … If there had been no such thing as petroleum, John D. Rockefeller would surely have found some other means of becoming stupefyingly wealthy. But if there had been no computers, what would have happened to guys like [Bill] Gates and Norton? Norton suspects that he might have ended up either as “an angry cab-driver with a Ph.D.” or as a paper-shuffling minion of some faceless corporation, much as his father was. The fact that big companies were beginning to use computers at the very moment Norton entered the job market was a hugely propitious accident for him— like becoming a teen-ager in the year they invented French-kissing.

I Bet He’ll Use His Wish to Improve the Knicks

Martin Schneider writes:

It wouldn’t be right to let Woody Allen’s 74th birthday pass without acknowledgment!

Happy birthday, Woody. May the bon mots keep flowing.

For the Next Style Issue

Benjamin Chambers writes:

With a few exceptions, The New Yorker has never gone in much for featuring tidbits from its past issues, but here’s one from a short Talk piece by Ian Frazier from the October 10, 1977 issue that should be highlighted in the next Style issue.

Attending a Parsons-New School lecture called “Fashion for the Consumer,” Frazier found “the most interesting part” was the slides shown by Dorothy Waxman of fashions seen on the street. Here’s the punchline:

One of the slides was of a woman stepping off a curb holding a little girl by the hand. “‘Look at this beautiful woman!’ said Dorothy Waxman. ‘Look at the stunning neutral palette of colors she has chosen—the hat just a slightly brighter shade than the jacket. The colors aren’t flashy, but they really come alive. And look at that beautiful little blond girl. What a wonderful accessory!'”

A Report: Nixon, Oppenheimer, Faust, and John Adams at Yale

In October we were very pleased to present Jenny Blair’s account of Platon’s New Yorker Festival event. Today Blair has volunteered to bring us a detailed report of a fascinating lecture by the composer John Adams in New Haven, which occurred last week.—Martin Schneider

Jenny Blair writes:

The composer John Adams visited Yale University last week to give the prestigious Tanner Lectures on Human Values.*Â This writer attended the second of the two lectures, held at the Whitney Humanities Center on October 29. (In the first, the composer discussed Thomas Mann’s fictional composer in the novel Dr. Faustus.)

A fine-featured and slender man with arching sprouts of white hair and a gracious manner, Adams spoke to a near-capacity crowd about the way that myth informs his operas. Though he is famed in part for having dramatized Nixon’s visit to China and, more recently, for the 2005 opera Doctor Atomic, which dramatizes the hours before the first atomic bomb was detonated, Adams is annoyed when he hears himself referred to as a “political composer” or his operas called “docu-operas.” Such appellations would seem to miss the point, which is that he seeks out universal themes within the famous particular. Events in history, he said, can rise to a mythic level, and these myths are a proper hunting ground for his music. “The themes I choose,” he said, “are not simply mere news, but rather human events that have become mythology. . . . [They are] a symbolic expression of collective experience.”

“Biography, history, and science have come to constitute our own myths,” he said, naming as examples Gandhi, Babe Ruth, 9/11, and the moon landing. “Andy Warhol understood the grip that iconic images have on us, . . . [such as] Elvis with a six-shooter, the electric chair, Marilyn Monroe.”

An indispensable element of myth is the supernatural, Adams said, and there is something about the media’s incessant repetition and manipulation of images and events that supernaturalizes those events. “When they saturate public consciousness, they become totemic. . . . [Some] rise to the status of myth.” Whether we know it or not, he said, we of the electronic age are saturated in myth.

9/11 is a classic case in point. Even with the same number of deaths, he said, “had it been a one-story warehouse somewhere in New Jersey, I don’t think that totemic power would have invaded public consciousness.” The endlessly replayed video clip of the Twin Towers’ collapse, he said, was a ritualistic reenactment.

It was Peter Sellars, director of the first, highly acclaimed production of Doctor Atomic, who suggested that Adams write an opera about Nixon’s iconic visit to China. At the time, Adams had been composing music about Carl Jung, and had even made a pilgrimage to the psychiatrist’s home in Switzerland. But he recognized the story of Nixon’s trip as “full to the brim with myths.” Capitalist meets Communist. Presidential vanitas. The narratives and personae created by people in power—this story had it all. “Both Mao and Nixon had made themselves into grandiose cartoons.”

Adams read aloud a portion of Alice Goodman’s Nixon in China libretto, in which Nixon is speaking. (One suspects he held back a rip-roaring mimicry.) Then he parsed it like a poem, noting references to 1930s ballads, Chekhov, and Apollo 11. A recording of the same passage as sung by original cast member James Maddalena was then played, and Adams, as he listened, made muted conductor-like waves of his bowed head.

To critics who charge that subjects like the atomic bomb or terrorism (a subject he treated in The Death of Klinghoffer, his 1991 opera based on the hijacking of the Achille Lauro) are events too serious to be appropriate for theater, Adams replies that such things are the stuff of myth. Moreover, terrorism, with its suicide bombers and innocent victims, is already a kind of theater. And as for Trinity, “there is no more emphatic image to [sum up] the human predicament than the atomic bomb. . . . That day, science and human invention sprang instantaneously to mythic levels.” Initially, Adams said, he had wanted to draw a parallel between J. Robert Oppenheimer and the soul-selling Faust of Goethe’s drama. But he eventually came to decide that inaction during the war would have required complete pacifism and an acceptance of “a long dark night of the soul,” whereas the Los Alamos scientists were devoted to winning a war against tyranny.

Yet once they built the bomb, said Adams, “the relationship between the human species and the planet irrevocably changed. It was a seismic event in human consciousness. . . . [Humankind now had the ability] to destroy its own nest.” Indeed, the physicist Edward Teller, in a letter Adams read aloud, wrote, “I have no hope of clearing my conscience. . . . No amount of fiddling . . . will save our souls.”

The libretto of Doctor Atomic was greeted by a torrent of criticism in the press for its unusual use of both natural language (as lifted from primary sources, like letters and biographies) and poetry, as well as a perceived lack of “verismo” in some of the arias. But Adams pointed out that not all operas are like Strauss or Wagner. The arias of Monteverdi and Mozart were written purely for poetic effect and stepped out of narrative time—as did Adams’s.

The composer ended his lecture with a few words about the first act’s final aria and a video of its performance by “my wonderful, wonderful” baritone, Gerald Finley. This aria takes place the night before the Trinity test, after an electrical storm has threatened the test. The music before this had flirted with atonality, Adams said, but the aria itself is in D minor, which conveys the “noble gravitas” of the poem. The storm blows over at last, and Oppenheimer is left alone with his thoughts. He sings a lightly adapted Donne sonnet, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.” The choice of this poem reinforces Adams’s decision not to compare Oppenheimer to Faust, for in it the narrator longs to reunite with God:

Batter my heart, three person’d God; For you

As yet but knock, breathe, knock, breathe, knock, breathe

Shine, and seek to mend;

Batter my heart, three person’d God;

That I may rise, and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force, to break, blow, break, blow, break, blow

burn and make me new.I, like an usurpt town, to another due,

Labor to admit you, but Oh, to no end,

Reason your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv’d, and proves weak or untrue,

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,

But am betroth’d unto your enemy,

Divorce me, untie, or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

After thunderous applause—the kind that tempts you to stand up and start an ovation—audience members stepped up to the microphones to ask questions. Highlights, lightly paraphrased:

Q: “Please give me water—my child is thirsty” were spoken as the last words of the opera. Why?

A: I realized I needed to hear the other side. Those words came from John Hersey’s Hiroshima. The woman who did the recording was a California university student, Japanese, and had a lot of piercings and tattoos.

Q: There are things in your opera that are fictional. For example, Kitty Oppenheimer is portrayed as the embodiment of the feminine principle, but Kitty was not like that at all. She was not a good mother; she left Oppenheimer; she ferociously wanted the project to succeed.

A: The real Nixon is to the operatic Nixon as the real Julius Caesar was to Shakespeare’s version. We’re working in the poetic realm. Moreover, I don’t agree with you about Kitty Oppenheimer. According to American Prometheus [Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography of Robert Oppenheimer], she was incredibly unhappy at Los Alamos. She was a scientist relegated to faculty-wife status. Anyway, I don’t see why a person who has character flaws can’t have profound human and moral feelings about war.

Q: The Kitty material is presented too densely for my taste.

A: I, too, have some difficulties with Muriel Rukeyser [the poet whose words appeared in the libretto during Kitty’s parts]. Poetry is unknowable—each of us brings to it our own personal experience. As for density, check out Othello. Works of art can be dense. It could be that over time people find that density to be something they can really chew on.

Q: Why did you repeat text in the sonnet? It’s not a sonnet anymore.

A: Your ear is tuned to prosody, mine to harmonic necessity. Even the Beatles say “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah.” The “yeah, yeah, yeah” there is to confirm the phrase. What I don’t like to do is melisma. It’s a great tradition in opera; it just doesn’t suit me as an American.

Q: Is there any subject you feel is prohibited in opera? What student idea would make you feel compelled to say, “This wouldn’t work”? What would you feel profoundly uncomfortable treating operatically?

A: If I say nothing, I’m immoral. If I say something, then I’m stuck. Next question!

Q: What are your bulwarks?

A: Sterility is the greatest danger. The theme of Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus is sterility. Popular culture is a bulwark against that sterility. Rap. Stravinsky’s imagined primitive dance forms. Bartok’s hummus of Hungarian sounds. . . . There is raw, uncooked life force in popular culture.

* [There doesn’t have to be a connection to The New Yorker for us to run a report of this quality, but for those who crave one, Adams wrote of his early days as a composer in avant-garde Berkeley and San Francisco for the August 28, 2008, issue, and Doctor Atomic was reviewed by Alex Ross on October 27, 2008. —MCS]