Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

“Order your Wavy Rule 2008 Anthology today!”:http://emdashes.com/2009/03/the-wavy-rule-anthology-now-fo.php

Monthly Archives: May 2009

Recent New Yorker Fiction Roundup

Benjamin Chambers writes:

I’ve been catching up on recent New Yorker stories, so I thought I’d provide a quick-ish summary of them, using a model I ripped off from Martin. [Warning: there are spoilers below.]

“The Slows,” by Gail Hareven (trans. Yaacov Jeffrey Green), May 4, 2009

Plot: An anthropologist has one last encounter with one of the “savages” he has studied for years, though he finds her kind repellent. The “savages,” like the anthropologist, are human, but they have refused a technique that greatly speeds human growth and development, setting them apart.

Key Quote:

No doubt the savages were a riddle that science had not yet managed to solve, and, the way things seemed now, it never would be solved. According to the laws of nature, every species should seek to multiply and expand, but for some reason this one appeared to aspire to wipe itself out. Actually, not only itself but also the whole human race. Slowness was an ideology, but not only an ideology. As strange as it sounds, it was a culture, a culture similar to that of our forefathers.

Verdict: You’ll like it if you don’t mind reductive parables disguised as fiction: humans invariably find reasons to justify their appetite for genocide.

“Vast Hell,” by Guillermo Martínez (trans. Alberto Manguel), April 27, 2009

Plot: A mysterious stranger arrives in a small (Argentinian?) town and is presumed to be having an affair with the wife of a barber. When the wife and stranger disappear, village gossips presume foul play. Efforts to find their bodies, however, unearth an unexpected tragedy.

Teaser Quote:

The horror made me wander from one place to another; I wasn’t able to think, I wasn’t able to understand, until I saw a back riddled with bullets and, farther away, a blindfolded head. Then I realized what it was. I looked at the inspector and saw that he, too, had understood, and he ordered us to stay where we were, not to move, and went back into town to get instructions.

Verdict: Absorbing, economical, but too abrupt. The implications of the surprise discovery at the end need more time to unfold, to become something more than an unpleasant event that touches no one.

Interesting Fact:Judging from Wikipedia’s entry on Martínez, this story is taken from a collection he published way back in 1989. (It’s his first to appear in TNY, as is Hareven’s piece.)

“A Tiny Feast,” by Chris Adrian, April 20, 2009

Plot: The changeling boy stolen by the fairies Oberon and Titania develops leukemia; uncomprehending, they must shepherd him through the horror of chemotherapy.

Key Quote:

Alice cocked her head. She did not hear exactly what Titania was saying. Everything was filtered through the same normalizing glamour that hid the light in Titania’s face, that gave her splendid gown the appearance of a tracksuit, that had made the boy appear clothed when they brought him in, when in fact he had been as naked as the day he was born. The same spell made it appear that he had a name, though his parents had only ever called him Boy, never having learned his mortal name, because he was the only boy under the hill. The same spell sustained the impression that Titania worked as a hairdresser, and that Oberon owned an organic orchard, and that their names were Trudy and Bob.

Verdict: Delightful though sad; a bit reminiscent of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s “Elphenor and Weasel.” The story only falters in its final paragraph, where the fairies are at a loss and the final lines seem insufficient to bring the piece to a close. [UPDATE: I see I didn’t make it clear that “Tiny Feast” is really an amazing story, and definitely worth reading.]

Interesting Facts:Adrian is a graduate of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, works as an emergency room pediatrician in Boston, and is this year supposed to get a degree from Harvard Divinity School. The man’s an overachiever; we’re lucky he’s a writer. I can’t wait to read the other three stories of his that have appeared in TNY.

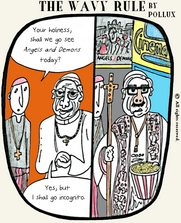

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: The Future of Kindling

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

“Order your Wavy Rule 2008 Anthology today!”:http://emdashes.com/2009/03/the-wavy-rule-anthology-now-fo.php

Michael Berube on the Race Donnybrook that Would Not Die

Martin Schneider writes:

I’ve been a fan of Michael Bérubé’s since I was in college (graduated 1992), and was charmed to have a brief exchange with him several years ago about an essay of his that apparently only I liked, about 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which he argues persuasively that the extremely common default reading of the movie, which involves some variation on the idea that HAL “goes crazy,” is indisputably contradicted by virtually everything that happens in the movie, and that the movie is really a political movie about the Cold War military-industrial complex. It’s an eye-opener.

Anyway. Bérubé’s exhaustively hyper-droll style always brings a smile to my face, even when he writes 2-3 times more than my attention span can handle (he kissed the Blarney Stone). Today he turns his attention to his only appearance in The New Yorker, a relatively dusty (1995) look at Cornel West and a few other African-American intellectuals who became more prominent in the mid-1990s.

Be forewarned; his post of today is not for everybody. I like Bérubé because he chases down a lot of nuance in people’s arguments that other writers wouldn’t bother with; plus he’s funny in a way that no academic of my knowledge is. But not everyone will take him the same way.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Joe Is the Volcano

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

“Order your Wavy Rule 2008 Anthology today!”:http://emdashes.com/2009/03/the-wavy-rule-anthology-now-fo.php

Ogawa’s Cafeteria in the Evening

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Following Martin’s example, when he used the random number generator to select Profiles to read from The New Yorker’s vast archives (his first was a three-part series on Chicago by A. J. Liebling from 1952), I decided to use it to find a short story to read from the archives.

The random number generator came up with “2004” (year “79” out of 84) and then the “36th” story out of 54 published that year: Yoko Ogawa’s story, “The Cafeteria in the Evening and a Pool in the Rain.”

I’d not heard of Ogawa before. She’s had two stories appear in TNY (both translated by Stephen Snyder), the most recent in 2005. I’m always curious about what tides of opinion and chance conspire to make a writer a frequent contributor to the magazine or a short-lived one, and of course it’s usually impossible to know. However, according to Ogawa’s Wikipedia entry, very little of her work has appeared English, although she’s written quite a lot. (Obviously, Snyder was trying to rectify that, so it’s not clear if the problem was really one of supply.)

In any case, the story’s narrator is a young woman in her early 20s who is about to marry an older man (“the difference in our ages was excessive”). They have selected a house together, partly to accommodate their dog, Juju. The woman is living in the house alone for the three weeks prior to their wedding, getting it ready, when a man and his 3-1/2-year-old son visit one afternoon.

The man’s behavior is odd and she takes him at first for a missionary before realizing her mistake. “Are you suffering some anguish?” he asks “abruptly.” Rather than turn him out on his ear, she considers the question seriously. He leaves after she finally observes that she doesn’t feel like answering:

Do I absolutely have to answer? I’m not sure I see any link between you and me and your question. I’m here, you’re there, and the question is floating between us—and I don’t see any reason to change anything about that situation. It’s like the rain falling without a thought for the dog’s feelings.”

The guy repeats her simile thoughtfully and then says, “I think you could say that’s a perfect response, and I don’t need to bother you anymore. We’ll be going now. Goodbye.”

She runs into the pair again while out walking her dog. The man’s staring in the window at the behind-the-scenes operation of the highly-mechanized school cafeteria, which prepares lunches daily for over 1,000 children. Once again, they have a slightly bizarre conversation.

She finds herself drawn to him, hypnotized a little by the stories he tells, and she begins to look for him when she’s out walking. It’s never clear what he does for a living though he speaks as though he has territory to cover, and at the end, that he and his son are “moving on” to another town the next day. (Because of this, he finally appears to be a bit unreal, a kind of good angel/therapist designed by the author to confront the character with riddles that will help her resolve her own internal–unstated and possibly unacknowledged–doubts.) The lack of detail about the narrator and the ordinariness of those that are supplied contrast strongly with the precise detail of the man’s own stories, making the piece reminiscent of Haruki Murakami’s work, and similarly intriguing.

The things the man says are dense and obscure as parables, and they nearly defeated me. (As the British novelist Nicholas Mosley says in his autobiography, Efforts at Truth, “The power of parables is that even then you still have to figure out everything for yourself.”) I ended up hanging the meaning of the story on its final paragraph:

[The man and his son] walked off in the fading light. Juju and I stood watching them until they became a tiny point in the distance and then vanished. I suddenly wanted to read my ‘Good night’ telegram [from my fiancé] one more time. I could feel the exact texture of the paper, see the letters, feel the air of the night it had arrived. I wanted to read it over and over, until the words melted away. Tightening my grip on the chain, I began to run in the opposite direction.

In other words, the “anguish” she’s been feeling is apprehension over her impending marriage. The man represents, in part, a different life, different choices. In the end, she runs toward marriage and away from the disconnected anomie represented by the man and his son. His mysterious “work” is done because he knows (how?) that she’s resolved her doubts.

Overall rating: worth a look, especially since Ogawa’s not a household name.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: Designer Labels

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

“Order your Wavy Rule 2008 Anthology today!”:http://emdashes.com/2009/03/the-wavy-rule-anthology-now-fo.php

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: The Laws of Money, the Lessons of Life…

Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

What’s in This Week’s New Yorker: 05.18.09

Martin Schneider writes:

A new issue of The New Yorker comes out tomorrow. A preview of its contents, adapted from the magazine’s press release:

In “The Death of Kings,” Nick Paumgarten presents a wide-ranging exploration of the economic crisis and its impact. “Much abridged, a few familiar words will do” to tell the story of the economic crisis, Paumgarten writes: “debt, greed, hubris.”

In “Don’t!” Jonah Lehrer examines recent evidence that indicates that self-control, not intelligence, may be the most important variable when it comes to predicting success in life.

In “Drink Up,” Dana Goodyear profiles Fred Franzia, the man behind Charles Shaw, a wine that sells for $1.99 at Trader Joe’s and is affectionately known as Two Buck Chuck.

Hendrik Hertzberg, in Comment, discusses Obama’s upcoming commencement addresses.

There is a “strange, but true” sketchbook by Roz Chast.

Ian Frazier writes an ode to turning forty—again.

Arthur Krystal looks at the life and works of critic William Hazlitt.

Anthony Lane reviews J.J. Abrams’s Star Trek.

John Lahr reviews the new Broadway revival of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

There is a short story by Salman Rushdie.

Sempé Fi (On Covers): Tiny, Little Scraps of Things

_Pollux writes_:

At last, with my column on covers, “_Sempé Fi_ “:http://emdashes.com/sempe-fi/, I have the opportunity to write about a cover by the eponymous “Sempé.”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semp%C3%A9

It was inevitable: “the work of Jean-Jacques Sempé”:http://www.cartoonbank.com/search_results_category.asp?mscssid=N75BLQT1QCKS9NR183NUWJWU397MBJ28&sitetype=1&sitetype=1&advanced=1&keyword=undefined&artist=Jean%2DJacques+Semp%E9§ion=covers&title=Jean-Jacques+Semp%E9+Covers&sortBy=popular is a staple of _The New Yorker_, appearing since 1978. Sempé is prolific, his work immediately recognizable, exhibiting a timelessness that some people find charming, others staid.

Sempé’s _New Yorker_ cover for May 4, 2009, called “Power and Grace,” typifies what over his long career has become his specialty: large, detailed landscapes, in which minuscule figures maneuver, sometimes haplessly and at times triumphantly. Sempé’s human figures are always diminutive but never inconsequential. His violinist is but a slip of a man dwarfed by an enormous plinth upon which an even larger piece of the landscape looms: a gigantesque and luscious hamadryad.

As _The Independent_ “pointed out”:http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/jeanjacques-sempeacute-luck-of-the-draw-420771.html in 2006, “most cartoonists like to zoom in on their idea: to focus on the joke for fear of losing it. Sempé loves detail and confusion. He often (not always) sets his characters in a large, jumbled world, whose mass of detail amplifies the punch line or leads you away in chaotically different directions.”

What do we make, then, of Sempé’s verdant image of an enormous statue and a man walking by it? Is she a joyful, voluptuous goddess of the summer season? Is she Terpsichore, muse of the dance, or Euterpe, muse of music, presiding over the advent of summer concerts in Central Park? Whatever deity she represents, she evokes power and grace. Her face is rhapsodic, her pose is free and perhaps physics-defying. She is liberated, sexual, and happy.

In contrast, Sempé’s strolling violinist is a tiny bundle of sexual repression. Whereas garments on Sempé’s sylvan goddess flow freely, with her emerald-green breasts and long legs exposed, the musician walking by her is stuffily dressed in suit, hat, and tie. He may be an artist, but he remains very bourgeois. He scarcely notices the 40-foot statue that looms above him.

Does a prurient thought cross his mind? It’s unlikely. He may be thinking about the gas bill or the price of tea in Bordeaux. He is hardly a satyr; that seems to be the joke. As Charles McGrath “writes”:http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/08/books/08semp.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss, Sempé’s figures are “Gallic Everymen, dignified and put upon at the same time, in the way that only French people can be.”

This Everyman, then, may be powerful and graceful in his own way. His power and his grace may come from the instrument he is carrying. It is only the proportion of the imagery that makes him seem unimportant. Unlike one of Thurber’s henpecked husbands, Sempé’s violinist is not intimidated by _Female Colossus With Arms Outstretched_.

“I’ve always been astonished that we humans assume somehow that we are big,” Sempé “has remarked”:http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/jeanjacques-sempeacute-luck-of-the-draw-420771.html. “If you look at a person beside a tree or a building or a town, we are just tiny, little scraps of things. I never consciously set out to draw that way…” And these days, more than ever, we humans are little scraps compared to forces potentially more powerful than ourselves: global warming, dangerous strains of influenza, nuclear weapons. O Muse, O high genius, aid us now.