Jonathan Taylor writes:

Following the nomination of Utah Governor Jon Huntsman (R) as U.S. ambassador to China, two posts on Evan Osnos’s “Letter From China” blog have some great notes (with reader assists) on the conventions in China for rendering foreign ambassadors’ names, by mere transliteration and/or a devised “Chinese name.” (Chinese characters TK, apparently.) Osnos writes, “I’ve received questions about whether I have a Chinese name. Answer: Ou Yiwen, stamped on me by early Chinese teachers. Like a lot of foreigners’ names in Chinese, it sounds a bit fancy—roughly akin to meeting a Chinese journalist in the U.S. who has taken the name Aloysius Sunbonnet or something.”

Monthly Archives: May 2009

Slightly Less Recent New Yorker Fiction Roundup

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Continuing in a format I adopted last week to provide mini-reviews of some recent stories from The New Yorker, I reach slightly farther back this week and throw in a more recent story by J.G. Ballard for good measure. [Again, watch out for spoilers below.]

Let’s begin, in fact, with the J.G. Ballard’s “The Autobiography of J.G.B.,” from the May 11, 2009 issue.

Plot: The main character, B (whom we are invited, because of the title, to associate with the author), wakes one day to find a world in which all other human beings have vanished. With little trouble, he adjusts and prepares for his own survival.

The Story’s Final Line: “Thus the year ended peacefully, and B was ready to begin his true work.”

Verdict: Ballard’s tricky, and his predilection for stories that blur the boundaries between autobiography and fiction don’t help a reader feel certain of his or her ground. He’s also very fond of post-apocalyptic worlds. But it’s hard not to read this very brief story, published posthumously after Ballard’s death on April 19th, as a comment about his own impending death. In a characteristically surprising reversal, J.G.B. doesn’t die, leaving teeming billions behind; instead, he alone is left to soldier on in the afterworld, while everyone else dies/vanishes. In this light, the story is actually quite poignant, though not weighty. (BTW, this is Ballard’s first appearance in TNY.)

Bonus Content: Tom Shone, author of a profile of Ballard that appeared in TNY in 1997, is interviewed in the May 11, 2009 issue of The New Yorker Out Loud.

“The Color of Shadows,” by Colm TóibÃn, which appeared in the April 13, 2009 issue, also hinges heavily on its final lines, as the Ballard story does.

Plot: Paul, a middle-aged man, returns home to Enniscorthy from Dublin after his aunt Josie, who raised him, falls and can no longer remain at home. He arranges for her to stay in an assisted living facility and visits her regularly until her death. Before she dies, however, she extracts a promise from him that he will not ever visit his mother.

Verdict: I won’t quote the final paragraph at length here, because it’s one of the few moments (if not the only one) in the story where the author allows himself to stray from a ruthlessly-restrained narrative long enough to suggest emotion. It works on Ernest Hemingway’s principle that the core of a story should remain submerged, like the bulk of an iceberg, while the visible portion (above the water, so to speak) should merely suggest the whole. Over the course of the story the back story becomes a little clearer; and though Josie raised Paul and Paul doesn’t remember his mother, his relationship with his aunt is more strongly characterized by duty than by love. You know he’ll keep his promise never to visit his mother, but it’s also clear he’s only beginning to realize what that will cost him. I can’t say the story’s to my taste, but it’s certainly well-made.

Similarly, the ending serves as the fulcrum of Craig Raine’s “Julia and Byron,” from the March 30, 2009 issue. (The image that keeps coming to mind to describe these author’s reliance on their stories’ closing words is that of the “slingshot effect,” where NASA used the gravitational pull of the outer planets to “sling” the Voyager spacecraft ever farther out into the solar system.)

Plot: Julia and Byron have been married a long time; happily, in his view, evidently not-so-happily in hers. At 62, she develops cancer for which she agrees to undertake radical treatments at the hands of a cynical doctor who has no ear for her sense of whimsy or personal hazard. She dies, horribly, in her husband’s arms, and he is undone by grief — for a while.

Final lines: “For two years he was a grief Automat, crying unstoppably at the mention of her name. Then he remarried–a younger woman–and was a difficult husband.”

Verdict: For my money, “Julia and Byron” is a more interesting read than “The Color of Shadows” because it’s difficult, for one, to guess where it’s going (Byron is introduced abruptly midway through, when Julia’s nearly dead); and for another, its surprising references to verse by A.A. Milne (quoted first mischievously by Julia, then by maudlin Byron). Julia’s the one you regret not getting to know, and that may be because Byron is histrionic, simple, while Julia appears unknowable and full of contradictions. Still, the final lines reduce the story to a homily on the impermanence of grief, or the permanent tendency of human beings to forget even their grandest passions. It’s not clear Raine meant for his final line to cast such a long shadow over the story (it’s quite possible he only meant it to be a comment on Byron), but either way, it mars it.

Finally, in “Visitation,” by Brad Watson, which appeared in the April 6, 2009 issue, we have exactly the opposite phenomenon: it’s not the last lines that sum everything up, it’s the opening paragraph.

Plot: Loomis is recently divorced and is in town visiting his young son. His entire trouble is encapsulated in the story’s opening lines: he’s a pessimist, and his depressed outlook saps the joy from his life, leaving him directionless and cut off from others. (Tellingly, he’s the only character in the story who’s given a name by the author. Loomis’ son is always “the boy,” etc.) The story consists of several episodes in which Loomis is threatened by an inexplicable outside world or irretrievably excluded from the happy world of others. The one person who breaks through to him, briefly, is a “Gypsy” woman who reads his palm and his character with the authority of a Delphic oracle, causing him to lapse into … well, pessimism and despair.

That Great First Paragraph:

Loomis had never believed that line about the quality of despair being that it was unaware of being despair. He’d been painfully aware of his own despair for most of his life. Most of his troubles had come from attempts to deny the essential hopelessness in his nature. To believe in the viability of nothing, finally, was socially unacceptable, and he had tried to adapt, to pass as a believer, a hoper. He had taken prescription medicine, engaged in periods of vigorous, cleansing exercise, declared his satisfaction with any number of fatuous jobs and foolish relationships. Then one day he’d decided that he should marry, have a child, and he told himself that if one was open-minded these things could lead to a kind of contentment, if not to exuberant happiness. That’s why Loomis was in the fix he was in now.

Verdict: I confess that I don’t have a lot of patience with stories whose entire narrative drive is carried by a vaguely unhappy middle-class white man who feels isolated and trapped, and his stasis is the point. The ironic humor of the opening paragraph peters out, unfortunately; and though the “visitation” by the so-called Gypsy is intense and promises some kind of transcendence, the narrator’s left back where he started.

But check these stories out for yourselves and see if you agree.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: The Innovators (#3)

A mini-series in honor of the “Innovators Issue”:http://www.newyorker.com/services/presscenter/2009/05/11/090511pr_press_releases of _The New Yorker_ (May 11, 2009). Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive, and “order your Wavy Rule 2008 Anthology today!”:http://emdashes.com/2009/03/the-wavy-rule-anthology-now-fo.php

Tonight: See Jane Mayer and Frank Rich (w/ New Yorker Discount)

Martin Schneider writes:

This found its way into my in-box:

Jane Mayer in Conversation with Frank Rich at the 92nd Street Y

Tuesday, May 19, 8 pm

Join Jane Mayer, New Yorker staff writer and author of the best-selling book The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals, and Frank Rich, New York Times Op-Ed columnist and author of Ghost Light: A Memoir, for a lively discussion on Mayer’s book, current events and issues of national security, civil liberties and American ideals.

New Yorker readers save 20% on the listed ticket price with the discount code FR20. Click www.92Y.org/Mayer, call 212.415.5500 or visit the 92nd Street Y Box Office, at Lexington Avenue at 92nd Street.

Emily, Jonathan, and I will be attending, so if you see us, by all means say hello!

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: The Innovators (#2)

A mini-series in honor of the “Innovators Issue”:http://www.newyorker.com/services/presscenter/2009/05/11/090511pr_press_releases of _The New Yorker_ (May 11, 2009). Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive, and “order your Wavy Rule 2008 Anthology today!”:http://emdashes.com/2009/03/the-wavy-rule-anthology-now-fo.php

Supreme Court Design Rules: Certiorari in Century, Please

Jonathan Taylor writes:

While we’re all talking about the Supreme Court: Anyone who has consulted an order or opinion on the Supreme Court’s site will know its attachment to the PDF, unsurprising given the format’s imperviousness to the vagaries of software. The staid, rather than stately, Century Schoolbook pages caged in one’s screen recall the defiance of David Souter amid the bells and whistles of Washington:

Turns out the court has some pretty stringent views on typography, and on the crafty task of assembling petitions, briefs and replies into little “booklets” for the justices to curl up with. From the Rules of the Court (PDF, natch, or HTML here):

Rule 33. Document Preparation: Booklet Format; 8½- by 11-Inch Paper Format

1. Booklet Format:

(a) Except for a document expressly permitted by these Rules to be submitted on 8½- by 11-inch paper, see, e. g., Rules 21, 22, and 39, every document filed with the Court shall be prepared using using a standard typesetting process (e. g., hot metal, photocomposition, or computer typesetting) to produce text printed in typographic (as opposed to typewriter) characters. The process used must produce a clear, black image on white paper. The text must be reproduced with a clarity that equals or exceeds the output of a laser printer.

(b) The text of every booklet-format document, including any appendix thereto, shall be typeset in Century family (e.g., Century Expanded, New Century Schoolbook, or Century Schoolbook) 12-point type with 2-point or more leading between lines. Quotations in excess of 50 words shall be indented. The typeface of footnotes shall be 10-point or larger with 2-point or more leading between lines. The text of the document must appear on both sides of the page.

(c) Every booklet-format document shall be produced on paper that is opaque, unglazed, 6 1/8 by 9 1/4 inches in size, and not less than 60 pounds in weight, and shall have margins of at least three fourths of an inch on all sides. The text field, including footnotes, should be approximately 4 1/8 by 7 1/8 inches. The document shall be bound firmly in at least two places along the left margin (saddle stitch or perfect binding preferred) so as to permit easy opening, and no part of the text should be obscured by the binding. Spiral, plastic, metal, and string bindings may not be used. Copies of patent documents, except opinions, may be duplicated in such size as is necessary in a separate appendix.

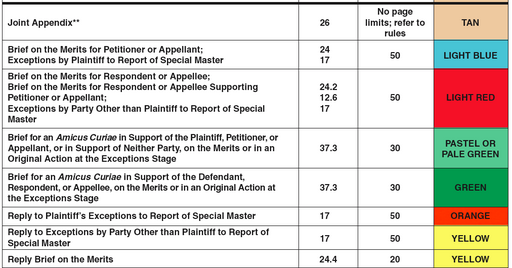

What’s more, there’s color-coded scheme for all those different types of supplications: your ordinary Petition for an Extraordinary Writ goes under a white cover, but a Brief for an Amicus Curiae in Support of the Defendant, Respondent, or Appellee, on the Merits or in an Original Action at the Exceptions Stage has got to be “dark green.” If you’re not sure what “light red” is, or you want to make sure your unglazed “tan” chapbook fairly screams “Brief Opposing a Motion to Dismiss or Affirm,” well, “The Clerk will furnish a color chart upon request”:

But note, it’s up to Counsel to “ensure that there is adequate contrast between the printing and the color of the cover.”

(In contrast, I’m a little surprised that, when it comes to adhering to word-count limits, “The person preparing the certificate may rely on the word count of the word-processing system used to prepare the document.” I wouldn’t want to test Clarence Thomas’s generosity with that rule.)

Via the promising site Typography for Lawyers, Ruth Anne Robbins, author of the manual (keep that Adobe Reader open) “Painting with Print,” suggests that the high court’s strictures might be necessary in light of lawyers’ slovenly word-processing habits. From the Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors, it’s a passionately footnoted plea for visually illiterate attorneys to wake up and smell the hot metal.

Irvin on a See-Saw: Two Rea Irvin Magazine Covers

Everybody loves “Rea Irvin”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rea_Irvin. It’s true. “Liza Cowan”:http://www.lizacowan.com/, lucky enough to own two original Rea Irvin magazine covers at her shop, writes about Irvin at “her blog”:http://seesaw.typepad.com/blog/2009/05/rea-irvin.html. And if you haven’t read it yet, “Emily’s article on Irvin”:http://www.printmag.com/Article.aspx?ArticleSlug=Everybody_Loves_Rea_Irvin is required reading for anyone interested in Irvinian Studies. You can minor in it here at Emdashes.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Pollux: The Innovators (#1)

A mini-series in honor of the “Innovators Issue”:http://www.newyorker.com/services/presscenter/2009/05/11/090511pr_press_releases of _The New Yorker_ (May 11, 2009). Click on the cartoon to enlarge it!

Read “The Wavy Rule” archive.

“Order your Wavy Rule 2008 Anthology today!”:http://emdashes.com/2009/03/the-wavy-rule-anthology-now-fo.php

New Museum 90s Panel: Roseanne Profile as Decade’s Time Capsule

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Friday night’s “The 90s vs. The 90s” panel discussion was occupied for a long time on what, either at the time or in retrospect, was “dark” or “light” about the decade, in the words of the moderator, n+1‘s Mark Greif.

The purest vein of nostalgia for the 90s was expressed by Aaron Lake Smith, 25. To him, the “public conversation was more interesting,” because, in its weird way, it was addressing “the roots of capitalism”—why did Columbine happen; Ross Perot and the “giant sucking sound”; the Zapatistas—as opposed to the sham of, say, today’s torture “debate.” Scott Hamrah—once of Suck.com, a URL worth a thousand Q&A’s—was quick to knock down young Aaron’s rosy version, countering that the “conversation” was about O.J., not Subcomandante Marcos.

At a certain point, Marisa Meltzer suggested that the middle period of the 90s was a high point of sorts for the well-being of women, on an arc described between the Anita Hill testimony (1991) and the Lewinsky affair (1998, although Meltzer zeroed in on that year’s premiere of “Sex and the City” as the decade’s Altamont). As evidence of the good times, she cited the 1995 New Yorker profile of Roseanne Barr—”it’s like something beamed to you from some era you never lived through and never will again” she said, or something close thereto.

Quite so. The article is likely overshadowed in many memories by the foofaraw over Roseanne’s consulting-editorship of the 1996 “Women’s Issue.” But after all the talk about authenticity and shallowness, John Lahr’s profile of Roseanne, who might be the closest thing to America’s Bertolt Brecht, is a heartening reminder of the substance that can be created by spectacle.

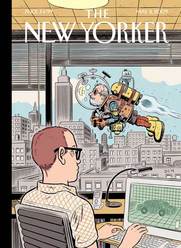

Sempé Fi (On Covers): Jet-Packing Through the Gates of Horn and Ivory

_Pollux writes_:

He wasn’t easily distracted. Occasionally a pigeon would flutter by; he wouldn’t look up. Sometimes his iPod malfunctioned and played the same song twice; he wouldn’t notice. You could hear Keane’s “She Has No Time” a million times anyway and never get sick of it.

But today was different. All was quiet and normal, and then suddenly he heard something that sounded like a cross between a backfiring ’58 Biscayne and a beer siphoning a homebrew. A sound like _PutTUTtatatataGLOOglooglooputputTUT_.

An old man was flying.

This old man didn’t mean to fly by the office of one of the city’s up-and-coming car designers (let’s call him Stephen), who is considered a true innovator by his peers and by Stephen’s new wife (he got married last month).

It was a good test run for the old man, and he didn’t end up falling out of the sky like a liver-spotted Icarus and dashing his brains on the corner of Broadway and Eighth.

The old man (let’s call him Buster) never went to college. This is the story of his life: he lied about his age in order to join the Navy, saw the world (mostly the Pacific) and saw some action on a swift-boat penetrating the Giang Thanh-Vinh Te canal system in North ‘Nam. He married his high school sweetheart and then lost her to cancer. He’s worked as a machinist, junkyard watchman, ticket collector on the railway, and sign-painter. He’s worked in a dead letter office, plastic packaging plant, textiles factory, and pet store. Buster has suffered from chemical burns on both hands, and currently suffers from high blood pressure, osteoporosis, and urinary incontinence. He remembers the friends he lost on the Giang Thanh-Vinh Te canal system. The only time he’s happy is when he’s tinkering around in his garage. Buster always wanted to fly, so he decided to build a jetpack.

If he had any friends, they’d laugh at him.

On the other hand, Stephen, our up-and-coming car designer, has plenty of friends. They envy his life and drink his expensive wine over a spirited game of Cranium. Stephen was a precocious child, and designed cool-looking soap-box racers when all of the other kids were duck-hunting with their Nintendoes. His excellent portfolio got him accepted to the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, where he learned 3-D modeling and where to get the best marijuana (Venice Beach) and the best Retro Nerd Square Glasses (again, Venice Beach). He won the prestigious EcoAuto Concept Award in 1998 and shook hands with the then-CEO of General Motors, John F. Smith, Jr.

Adhering to the “theory and practice” approach to learning, Stephen met with practicing designers, engineers, and anyone remotely connected with the auto industry. He did a summer internship at the UmeÃ¥ Institute of Design, in Sweden, and after his time at Pasadena, did a two-year automotive stylistics program at the Istituto di Scienze dell’Automobile, in Modena, Italy. Modena was the source of much of the wall decorations that brighten up Stephen’s spacious New York apartment. It was a cinch for him to find a job in a car design firm in the Big Apple in a time when the economy had not yet sunk like a power boat with badly made deck-to-hull joints. Stephen had done everything right.

Such is the dichotomy presented on “Dan Clowes'”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Clowes cover for the May 11, 2009 issue of _The New Yorker_, called “Leading the Way.” The May 11, 2009 issue is the Innovators Issue, and Clowes is an innovator in his own right, having created works that transcend the appellation of “comics” and are instead works of literature that happen to be fully illustrated, the best known perhaps being “_Ghost World_.”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_world

Clowes’ artistic style is not necessarily photo-realistic but always appears as if his subjects have been drawn from life, penciled on a subway and then inked carefully at home. You feel as if Clowes has seen a young man like Stephen somewhere, as well as an old man like Buster, perhaps not necessarily flying on a jet-pack. The _New Yorker_ cover coincides with the announcement of a new book by Clowes, as yet unnamed, that concerns, as stated in “this interview”:http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2009/05/sneak-peek-dan-clowes.html, “a guy whose father dies, and he’s completely alone, so he tries to reconstruct what he’s lost, to approximate a nuclear family by joining people together.”

Clowes’ jet-packing senior also seems like someone who is completely alone, who has built his dream out of spare mechanical parts and perhaps an old fishbowl. Clowes has drawn outsider innovators before. His “May 12, 2008 cover”:http://www.cartoonbank.com/product_details.asp?mscssid=N75BLQT1QCKS9NR183NUWJWU397MBJ28&sitetype=1&did=5&sid=125205&pid=&keyword=Dan+Clowes§ion=all&title=undefined&whichpage=1&sortBy=popular depicted a two-page act of creation. An inventor builds himself a powerful robot just so that he sit down to a good game of cards. In the same way, Clowes’ jet-packing senior just wants to fly. He’s not trying to revolutionize the airline industry.

And then there’s the young, hip car designer: all this education and experience under his belt, and Stephen has ended up designing a fairly conventional-looking car.

Who remains deskbound, boring, and conventional? Stephen.

But who flies as free as a bird? Buster.

Sometimes the old, and the old-school, lead the way.