Jonathan Taylor writes:

My normally flatline sense of anticipation the Nobel Prize for Literature is a bit aroused this year, since I’m grateful, as an admittedly insular American, to have been introduced to J.M.G. Le Clézio last year.

The Nobel Committee has set dates for the announcement of the other prizes, beginning October 5. “According to tradition, the Swedish Academy will set the date for its announcement of the Nobel Prize in Literature later.” (It’s typically a Thursday.)

Anybody have an interesting line on this year’s possibilities? Or, better yet, flights of fancy on the glorious impossibilities?

Author Archives: Jonathan

Unoccasioned Link Roundup: Dimanche Apres Midi Edition

Jonathan Taylor writes:

I’ve bought the New York Film Festival ticket I want, I’m listening to “Bal de Dimanche Apres Midi” streaming from KRVS in Lafayette, La. (the French-speaker next to me on the sofa “can’t understand a word”), on the day after Emily’s birthday—here are some New Yorker–related links:

- “Repetition is funny.” “Neither rodent is presently using the wheel.” P.L. Frederick takes the time to break down the visual touches that make New Yorker cartoons funny (the funny ones, that is). And in her hands, it takes no time at all.

- Only an affectionate reader could rustle up this snark about Judith Thurman’s Critic at Large on Amelia Earhart. (Lindsay Robertson also has “further reading” for everyone ensorcelled by the David Grann death penalty piece.)

- The Times wonders how Derek Jeter would stack up against Lou Gehrig as profiled in The New Yorker in 1929. Plus, more of Gehrig’s magazine appearances, courtesy of New Yorker librarian Jon Michaud.

- Via Andrew Sullivan, Charles Murray, of all people, sets himself straight about the infamous line falsely attributed to Pauline Kael about Nixon’s 1972 victory. Kael also figures in the Times‘s proper appreciation of Andrew Sarris.

- Not a New Yorker link, but, speaking of the radio: everything you needed to know about radio station call letters’ begining in K or W.

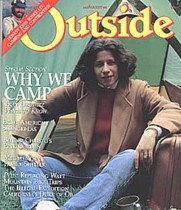

Old Magazine Articles We Wish Were Online: Fran Lebowitz in the Woods

Raided Museum Was a ’30s ‘Culture Center’

Jonathan Taylor writes:

The Upper West Side’s Nicholas Roerich Museum, City Room reports, was recently the victim of its first art thefts. The museum was the topic of “Culture Center,” a Talk of the Town piece in 1934. (The museum was founded well before 1949, when the Times says it was). At the time, the museum was still located in the notable Art Deco building originally constructed to house both it, with its collection of a thousand Roerich paintings, and apartments for members of the theosophic Roerich Society: the Master Apartments on 103rd and Riverside. (The museum is now in a townhouse at 107th and Riverside.)

Talk called the 29-story building “the only building in town, so far as we know, that shades from deep purple at the base to white at the pinnacle. This symbolizes the idea of growth,” and, judging by the museum’s site, the colors retain their power. The piece continues archly about Roerich’s, and the Roerich Society’s, assiduous deployment of symbols.

The upper 25 stories of the building were “small kitchenette apartments for resident members of the Roerich Society.” Some became members just by virtue of signing a lease for a (nonprofit) apartment. A lease conferred an instant intellectual and social life: nightly talks on such topics as “What is Happening in the World and Why,” and birthday parties staged for folks like Goethe, Bolivar and Buddha—celebrated on the full moon of May. (The museum’s current event listings haven’t been updated lately.)

A Paris Roerich Museum is mentioned—can’t quite tell if that’s still around, but there are others in Mongolia, in a house he resided in, and in Moscow, which delightfully preserves in translation the Russian genitive form imeni, “by the name of,” for things named after people.

We’re Liberal and We Drink Vinegar

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Michael Savage is right. Vinegar is “like wine.” (It’s a trick!) I recently received, as a thoughtful gift, a “drinking vinegar” from Gegenbauer, a fine Viennese producer of vinegars (as well as whole grains and coffees), via Philadelphia’s DiBruno Bros. This one is made from the Pedro Ximénez grape, used to make sherries and raisin wines. It is appley and brisk, with enough acidity to induce a challenging euphoria resembling that of capsicum, but, at 3%, not enough, in fact, to technically be categorized a vinegar. This “Noble Sour” is, pace Savage, “special,” an after-dinner drink with a world-clarifying potency that an alcoholic digestive could not provide. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s already on menus in Savage’s San Francisco, and it has a place on more. Don’t anybody tell him about saba .

Start Smiling: Not the New Yorker Map of the U.S. You Were Thinking Of

Jonathan Taylor writes:

We noted the new book about the new book about the short-lived, full-throated, New Yorker–inspired Chicago magazine of the 1920s, The Chicagoan. But any chance to see more brash images from the mag is welcome: Here’s a slide show from Stop Smiling magazine (a stylish successor of sorts).

See especially the proto-Steinbergian “New Yorker’s Map of the United States,” and spot the tiny number of places that ≠ Dubuque. Reno, Nevada, didn’t seem to loom as large for The New Yorker as the map would suggest….

‘Imagine That Confronting You on a Newsstand!’ Creative Editor Creatively Lampooned

Jonathan Taylor writes:

The Daily Telegraph‘s obituary of the legendarily legendary editor of Flair magazine, Fleur Cowles, notes that she was the subject of a parodic piece in the New Yorker.

“The Hand That Cradles the Rock” (July 1, 1950), by S.J. Perelman, emits a chauvinistic condescension as it quotes at length an admittedly fawning portrait of Cowles (“‘I’m just a generally creative person,’ she says modestly”). But then follows a livelier speculative playlet, about an explosively innovative (and totally fictional) redactrix, Hyacinth Beddoes Laffoon, “queen-pin of the pulp oligarchy embracing ‘Gory Story,’ ‘Sanguinary Love,’ ‘Popular Dissolution’ and ‘Spicy Mortician.'” The scene finds Laffoon, “chic in a chiffon dress for which she herself spun the silk this morning,” in conference with the obseqious editorial assistants of her magazine, Shroud:

HYACINTH: First, these covers we’ve been running. They’re namby-pamby, no more punch than a textbook. Look at this one—a naked girl tied to a bedpost and a chimpanzee brandishing a knout.

BUNCE: I see the structural weakness. It demands too much of the reader.

But wait, here’s the beauty part—I mean, “The Beauty Part“—the full-length play that Perelman wrote his Laffoon character into, with five parts for Bert Lahr. Reviewing a 1992 Yale Rep revival, the Times said that “few flops have been as celebrated, mulled over and positively entitled to cult status,” but suggests:

In contrast to the capacity for self-reproachment of genuine contemporary artists, currently evidenced by “The Player,” the film about Hollywood backstabbing, and “Sight Unseen,” the play about sham in the art world, Perelman’s barbs about art as a commodity, the uncurbed need for self-expression and the mass marketing of culture — or to be an exact Perelmaniac, “Amurcan Kulchur,” are tepid indeed.

I wonder if that still the case, or might we benefit anew from a satire on

artists who do “collages out of seaweed and graham crackers,” or who sculpture in soap on “Procter & Gamble scholarships”; writers like one Kitty Entrail, “an intense minor poetess in paisley,” and suburban consumers (here Gloria and Seymour Krumgold) who commission a heat-resistant painting on Formica “as long as it doesn’t clash with the drapes.”

Annals of Cartography: Will Google Incorporate Broadway Closure?

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Pedestrians, beware iPhone-bearing out-of-town drivers: Checking in on Google Maps’ driving directions, it seems like one is still instructed to plow through the parts of Broadway recently closed to vehicles.

Gratis Greens: The New Yorker’s Guide to Foraging

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Heirloom food culture is converging with the New Thrift, even if many practices, like shopping farmer’s markets and the home canning featured in the Times Wednesday, are most readily practiced by those with a surplus of time, if not money. The Wall Street Journal Wednesday charted a number of nutritious greens that were once commonly eaten but now proliferate, unnoticed and underfoot, in the guise of weeds. They’re had at greenmarkets for greenbacks, but are ripe for wider rediscovery as an opportunity for frugal foraging.

As the Journal notes, plants like purslane and sorrel went by the wayside by the mid 20th century, as “immigrants and rural Americans moved to cities, leaving behind both their gardens and their ethnic origins.” In 1943, during World War II days of rationing, The New Yorker‘s Sheila Hibben offered a timely reminder of “those perfectly edible greens which in happier times we called weeds.” Hibben’s “Markets and Menus” department was normally given over to the offerings of carriage-trade suppliers of glazed hams, cookies and wine.

- Milkweed: “as succulent and tender as any asparagus that has been made to grow by toil and patriotic enterprise” (Hibben raised the specter of the “shiftless country dweller” who might exploit “an untrimmed roadside” while “industrious Victory gardeners” labored away in their plots); to be harvested “just when the young shoots have pushed up to no more than six inches or so out of the ground.”

- Home-cut fern tips: “likely to be a fresher and altogether pleasanter green than the vegetable which used to come to town all worn out by the long trip down from Maine”; “serving them provides a satisfying pride and comfortable sense of living off the land.”

- Sorrel: “at this very minute is probably taking possession of your strawberry bed”; “Soft-cooked eggs or egg timables turned onto a bed of creamed sorrel provide as handsome a lunch dish as you could want of a hot day.”

- Dandelion: “only the very young dandelion leaves are edible and they must be cut far enough below the ground so that they are partly etiolated.” (???)

- Pokeweed shoots: “a slight, rather pleasant taste of iron”; “should be washed and carefully scraped and left in cold water for an hour”; “you had better look out” for poison in older plants. (The Journal says, “Eat with caution if at all,” cooking in at least two changes of boiling water.)

- Wild mustard: “more generally accepted socially,” and good boiled with bacon. (“If bacon makes too great a strain on the ration book, you’ll find that bacon rind, which has only a one-point value, adds the same rich flavor.”)

- Purslane: known as “pussley” by American farmers, and good “just to eke out a dish of boiled spinach.”

But note to New Yorkers: foraging in city parks is illegal without a permit, but there are sanctioned foraging tours by “Wildman” Steve Brill (Adam Gopnik went on one in 2007.)

Summoning Clear-and-Bright-Plum! The Naming of an Ambassador

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Following the nomination of Utah Governor Jon Huntsman (R) as U.S. ambassador to China, two posts on Evan Osnos’s “Letter From China” blog have some great notes (with reader assists) on the conventions in China for rendering foreign ambassadors’ names, by mere transliteration and/or a devised “Chinese name.” (Chinese characters TK, apparently.) Osnos writes, “I’ve received questions about whether I have a Chinese name. Answer: Ou Yiwen, stamped on me by early Chinese teachers. Like a lot of foreigners’ names in Chinese, it sounds a bit fancy—roughly akin to meeting a Chinese journalist in the U.S. who has taken the name Aloysius Sunbonnet or something.”