Martin Schneider, our trusty Squib Reporter, writes:

On Wednesday, Emily noted: “And R.I.P., too, Elizabeth Tashjian, who seems to have been, among many other things, the subject of a New Yorker piece.”

Yes, she was; more than one, in fact. Two times, more than twenty years apart, she was the subject of a Talk of the Town item. The dates are March 26, 1984, and April 18, 2005. The first one, “Raided,” by William Franzen, covered the hibernatory habits of small northeastern museums like Ms. Tashjian’s Nut Museum. Her problem that winter, and for all I know every winter, was that hungry chipmunks and squirrels were prone to invade the museum, eager to usurp all the nutty goodness. We see her deciding to place her museum’s holdings under glass, but she has a place in her heart even for the greedy little poachers: “They’re making a nut museum of their own, I guess.” Note that Franzen does not call her the Nut Lady.

The second piece, “Legacies,” by Tad Friend, is especially poignant, as it has largely to do with her impoverished last years. Somewhat strangely, Friend does refer to her as the Nut Lady, even though he states quite clearly that she dislikes the nickname. Still: Friend puts the focus squarely on her plight, emphasizing her loss of control over her holdings. We learn that after being declared a ward of the state, she won back her

right to manage her own affairs. However, her museum had been sold to a woman who them cut down her nut trees (!); the item ends by describing a dispute over her (at the time) eventual burial. All in all, a terribly affecting article.

The only real question left is: Will Ms. Tashjian be interred in a plot of her choosing? I hope so.

Category Archives: Hit Parade

Friday Morning Guest Review: Afternoon of a Shawn (Wallace Shawn’s “The Fever”)

Martin Schneider, our trusty Squib Reporter, writes:

Last night I went to see Wallace Shawn—son, of course, of William—deliver his monologue/play The Fever at the Acorn Theatre on 42nd Street. When I entered the auditorium, there was a clot of people on the stage. Ah yes, I recalled, anyone viewing the performance was encouraged to “join Mr. Shawn for a sip of champagne one half hour before each performance.” It’s only after the play that the lacerating bite of the gesture becomes evident.

My companions and I observed that sipping champagne in a crowd full of theatergoing New Yorkers came perilously close to “hobnobbing.” When we spotted Ethan Hawke on the other side of the stage, we realized that hobnobbing status had indeed been attained. (Shawn appeared in the New Group’s 2005 production of Hurlyburly, starring Hawke; both The Fever and Hurlyburly were directed by Scott Elliott.)

Before assuming his character of “the Traveler,” Shawn spoke for a few minutes about the strange conventions of theater. Theatergoers like to go to plays even though they are fully aware that plays are awful; the conventions involved in theater programs are mystifying; disembodied voices with demands about our cell phones are over-hasty; and so on. Charming and astute.

The play is about the unsettling thoughts of any educated, cultured person: Who had to toil so hard so that I could enjoy this latte? Do my fondness for Schumann and my considerate manners represent any contribution to the public weal? On what basis can my privileged status be justified? And so on. It’s brave and thought-provoking stuff, and I enjoyed it a lot. For a clever fellow, Shawn is awfully dark. Or possibly the other way around.

I also liked him in the underrated 1985 movie Heaven Help Us.

The Fever is playing through March 3 at the Acorn Theatre, 410 West 42nd Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues. Performances are Monday-Friday at 8 p.m., Saturday at 2 p.m.

Ask the Librarians (IV)

A column in which Jon Michaud and Erin Overbey, The New Yorker’s head librarians, answer your questions about the magazine’s past and present. E-mail your own questions for Jon and Erin; the column has now moved to The New Yorker‘s Back Issues blog. Illustration for Emdashes by Lara Tomlin.

Q. I’ve read that the filmmaker Terrence Malick’s first occupation, along with teaching philosophy at M.I.T., was writing for The New Yorker. Did he write under a pseudonym, and what kinds of articles did he write?

Erin writes: Terrence Malick (who directed The New World and Badlands, among others) did indeed write for The New Yorker, but his byline never appeared in the magazine. His only article for us was a “Notes and Comment” piece on the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., co-written with Jacob Brackman and published in the April 13, 1968, issue. Neither the Comment nor the Talk of the Town section were signed by the writers in those days, so it is easy to see how this piece might have escaped the notice of Malick fans.

Malick and Brackman’s Comment offers a poignant first-person account of the immediate days after the assassination:

[B]y Sunday—Palm Sunday—things had changed. As marchers gathered,

twenty abreast and eventually seven dense blocks long, at 145th Street and Seventh Avenue, and as they marched…black and white, arms linked, down Seventh Avenue, there was a sense that the non-violent, freed ever so slightly by the President’s speech of last week from the dividing pressure of Vietnam, were returning in force to civil rights…. The march was informal—no marshals and no leaders…. Little boys standing at the entrance to [Central] Park put their feet in the line of march, as though testing the water, and then joined in…. The Mall, by the time the marchers got to it, was filled with a crowd several times the size of the march itself…. We stood on the hill in back of the Mall and watched the two crowds merge. They did so almost silently, and totally, in great waves…and [from the distance] it was hard to tell who was black and who was white.

After his brief stint at The New Yorker, Malick earned his MFA from the AFI Conservatory, and, in 1973, Warner Bros. released Badlands, which was widely admired. The following year, The New Yorker‘s movie critic, Pauline Kael, panned the film in the magazine. (“The movie can be summed up: mass-culture banality is killing our souls and making everybody affectless. ‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ said the same thing without all this draggy art.”) According to Ben Yagoda’s About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made (2000), William Shawn was unhappy with Kael’s review, protesting that Malick was “like a son” to him. Her response? “Tough shit, Bill.”

Q. Could you tell me more about illustrator Pierre Le-Tan and the work he has done for The New Yorker?

Jon writes: Pierre Le-Tan was born in Paris in 1950, the son of the Vietnamese artist Le-Pho and a Frenchwoman. He made his debut in The New Yorker at age nineteen, initially contributing spot illustrations. His first cover appeared in 1970—a Valentine’s Day cover depicting a red heart viewed through an open window. Since then, he has contributed eighteen covers (his last was in 1987) and more than fifty illustrations (most recently in 2005).

Le-Tan was one of a number of European artists, including Andre François and Jean-Jacques Sempé, whose work started to appear in the magazine in the late sixties and early seventies. Initially, his covers and spots were predominantly still-lifes and studies of architectural details. In the late eighties, when The New Yorker broadened the scope of the editorial art in its pages, Le-Tan began doing portraits for the magazine. He did drawings of Simone de Beavoir, Nelson Algren, Anthony Hopkins, and Bruno Bettleheim, among others. His most recent work for the magazine was a collaboration with George Saunders in the Sept. 26, 2005, issue that paid tribute to the verse and art of Edward Gorey.

In addition to his magazine work, Le-Tan is much in demand as an illustrator for posters and children’s books. His published books include Remarkable Names (1977), Happy Birthday, Oliver (1978), and Cleo’s Christmas Dreams (1995).

Q. How was the decision made to add television as a Critics category, and how often does it appear?

Erin writes: The column on television has gone through several incarnations at the magazine. It was first introduced by Philip Hamburger in the October 29, 1949, issue under the department heading “Television.” In his book Friends Talking in the Night (1999), Hamburger wrote that it was editor Harold Ross who—”under the impression that television was here to stay”—suggested that he write a column on the medium. Hamburger’s “Television” ran from 1949 to 1955, and it covered such diverse broadcasting topics as Allen Funt’s Candid Camera, Edward R. Murrow’s See It Now programs on Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, and the emergence of color television. The column lapsed for a few years after Hamburger moved on to write “Notes For a Gazetteer,” but it soon reappeared under the heading “The Air,” by John Lardner.

Lardner wrote “The Air” from 1957 to 1960, and then the column was written by Michael J. Arlen, from 1967 to 1982. Arlen’s reviews covered some of the most important television events in those decades: broadcast news coverage of the Vietnam War and Watergate; the 1968 Democratic National Convention; the creation of Sesame Street and Saturday Night Live; the phenomenon of Roots; and so on. According to About Town, Arlen’s early television reviews were fairly conventional, but he “quickly began to see—and write about—television as one grand spectacle, alternately horrifying and absurd, with images of Vietnam, the 1968 Democratic convention, football games, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, and Petticoat Junction all running together.” After Arlen’s departure, “The Air” was retitled “On Television” and reintroduced by James Wolcott, who wrote the column from 1992 to 1995. In 1998, Nancy Franklin became the magazine’s television critic, and she continues to write the column—which generally runs about fifteen times a year—today.

Q. Aside from The Reader’s Guide, is there any way to look up old New Yorker articles?

Jon writes: Over the years, there have been several published indexes of material from The New Yorker. In 1946, Thomas S. Shaw, a staff member at the Library of Congress, published an Index to Profile Sketches in the New Yorker Magazine (Boston, F.W. Faxon Co.). Shaw’s index was designed to fill the gap between 1925, when The New Yorker started publishing, and 1940, when The Reader’s Guide began indexing the magazine. In addition to listing the subjects of the magazine’s Profiles and other personality pieces by name and occupation, the book included contact information for libraries with a complete set of The New Yorker in their collections.

A more comprehensive index by Robert Owen Johnson was published in 1971 and contains a full index of The New Yorker from 1925 to 1970. (An Index to Literature in the New Yorker, Metuchen, N.J., The Scarecrow Press). Until recently, it was the only comprehensive index to the magazine available to the public.

More recently, several digital indexes of the magazine have become available. The New Yorker has been distributed to Lexis-Nexis and ProQuest since 2000. While the cost of these subscription databases can be prohibitive to individual users, many library systems, including the New York Public Library, make ProQuest available to their members.

The Complete New Yorker, released in 2005 and updated in 2006, features a searchable index of articles, covers, and cartoons and every printed page of the magazine’s first eighty years and is available on eight DVDs or on a portable hard drive. This is currently the most efficient way to find and read old New Yorker articles. Some libraries, including the Mid-Manhattan branch of the N.Y.P.L., have made The Complete New Yorker available to their users. The Complete New Yorker is available at www.cartoonbank.com.

Q. Who does the little black-and-white drawings (not the Tom Bachtell caricatures) that appear at the start of each Talk of the Town piece?

Erin writes: The small, spare drawings at the beginning of each story in the Talk of the Town section have become a staple of The New Yorker. They are all the work of artist Otto Soglow, who provided more than eight hundred cartoons and tiny uncaptioned illustrations for the magazine before his death in 1975. Soglow began contributing to The New Yorker in November of 1925, and he continued publishing drawings with us for the next forty-nine years. During his time here, he drew illustrations for the Talk section every week; those drawings have been re-used for that section by the editors since his death. In the obituary the magazine ran in the April 28, 1975, issue, William Shawn wrote that Soglow’s work “became purer and purer, until, finally, a Soglow was a drawing without a single detail that could be called extraneous, without any embellishment, without a line that did not seem essential or inevitable.” Several collections of Soglow’s work were published in the early 20th century, including Everything’s Rosy (Farrar & Rinehart, 1932) and The Little King (John Martin’s House, 1945). None of his books are still in print, but a few can be found in used condition on Amazon.

Q. Is it true that at some point in the seventies, Goings On About Town used the listings for The Fantasticks to serialize James Joyce’s Ulysses?

Jon writes: Yes. The New Yorker began serializing Ulysses in the November 23, 1968 listing for The Fantasticks, which famously ran for 17,162 performances, or nearly 42 years. That issue quoted the copyright information from the third printing of the novel (London, Egoist Press). The book’s opening words—”Stately plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed”—appeared in the Dec. 21, 1968, issue. The serialization lasted almost three years, ending in November of 1971, and encompassed the entirety of the book’s first chapter. By the end, Ulysses had spread to the listings for other long-running musicals such as Hello, Dolly!, and Fiddler on the Roof. For about six months prior to serializing Joyce’s novel, the magazine had filled the Fantasticks listing with geometry (“The sum of the squares of the two other sides”), grammar (” ‘I’ before ‘e,’ but not after ‘c’ “), instructions for doing your taxes (“If payments [line 21] are less than tax [line 16], enter Balance Due”), and other nonsense.

In 1970, New Yorker editor Gardner Botsford explained to Time magazine that he began the serialization of Ulysses because he got bored writing the same straight capsule reviews week after week. Asked about reader response to the serialization, Botsford observed, “Many are delighted they can identify the excerpts, but others think we are trying to communicate with the Russian herring fleet in code.”

Time noted that Botsford might have been inspired by one of The New Yorker‘s own writers. Robert Benchley handled theatre listings for the original Life magazine in the twenties, and once wrote of the long-running Abie’s Irish Rose: “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten.”

Addressed elsewhere in Ask the Librarians: VII: Who were the fiction editors?, Shouts & Murmurs history, Sloan Wilson, international beats; VI: Letters to the editor, On and Off the Avenue, is the cartoon editor the same as the cover editor and the art editor?, audio versions of the magazine, Lois Long and Tables for Two, the cover strap; V: E. B. White’s newsbreaks, Garrison Keillor and the Grand Ole Opry, Harold Ross remembrances, whimsical pseudonyms, the classic boardroom cartoon; IV: Terrence Malick, Pierre Le-Tan, TV criticism, the magazine’s indexes, tiny drawings, Fantasticks follies; III: Early editors, short-story rankings, Audax Minor, Talk’s political stance; II: Robert Day cartoons, where New Yorker readers are, obscure departments, The Complete New Yorker, the birth of the TOC, the Second World War “pony edition”; I: A. J. Liebling, Spots, office typewriters, Trillin on food, the magazine’s first movie review, cartoon fact checking.

The Squib Report: The Best American Complete New Yorker

Martin Schneider, the man behind the admirably focused and semi-extant Between the Squibs, has kindly agreed to contribute an occasional column, in which he’ll spelunk into the Complete New Yorker archives and tell us what he’s uncovered. Here’s the column’s debut. Martin filed this yonks and yonks ago (as Georgina and Brian would say), but I got all busy and distracted, so I’m just posting it now; mea culpa! I’m sure you’ll agree it’s well worth the wait.

Recently I started Between the Squibs, a blog about the New Yorker DVD set. And then ever so slightly more recently I abandoned said blog. Fortunately, some months later, Emily has kindly granted me a little space here in her demesne. Some friends of mine and also some kind blog-commenters let me know what a shame it was that I’d given up “BtS,” and I found it hard to explain why I found it hard to write to a public consisting of the purchasers of a DVD set, hard to write about content that has a $60 price of entry and is not easily duplicated.

And then in September, long after “BtS” had gone dark, right about when I started here, I began cultivating some inklings about hidden utility, hidden Emdashes utility, in the “Best American” series. You know, those Houghton Mifflin books, The Best American Essays, The Best American Travel Writing, The Best American Short Stories…there are others. Those books, you see, almost exactly fulfilled the mandate that I had originally laid out for “BtS”: to act as a sensible and independent (in the sense of existing outside of my head) guide to genuine highlights to be found in the Complete New Yorker DVDs. At least for recent years.

Because—and surely this will not come as a surprise—The New Yorker really does dominate those books. It’s the rare volume that doesn’t have three New Yorker articles reprinted in full and another dozen listed in the appendix. I know, because I went to my local library and copied down all the New Yorker titles in every “Best American” book I could find—specifically the Travel, Essay, and Story ones. Right now I have 19 “Best Travel” articles pinned to my CNY’s reading-list panel, 133 “Best Essays,” and 93 “Best Stories.” “Best Science”? I’ve only got 15 of those so far. And all of those lists are far from complete.

“BtS,” your days always were numbered. But I’ve had a ball dipping into those volumes, and you’ll be hearing about some of my discoveries in the weeks to come. In fact, maybe I’ll even release the spellbook to the apprentice wizards reading this and just, doggone it, compile a list of the New Yorker pieces that have been cited in those books as a resource, and then Emily can post it here so that you all don’t have to swarm actual, physical libraries and even, heaven forfend, pester actual physical librarians for the treasures. Stay tuned for that.

I’ll leave you with this: the first significant discovery to emanate from my Mifflin Hunt was David Schickler. I didn’t have the vaguest idea that he was this good. He may be a little showy, but I prefer to see it as “originality†and “verve†just now, thank you. “Jamaica” is definitely the best story I have ever read that combines the hobbies of archery and book clubs—and “Wes Amerigo’s Giant Fear” is even better. Go read.

Cover Boys, and What These Categories Mean

Barry Blitt’s “Deluged” cover (Sept. 19, 2005) won best cover of the year, and Mark Ulriksen’s Brokeback Cheney (Feb. 27, 2006) best news cover, in the new annual contest run by the American Society of Magazine Editors and the Magazine Publishers of America. (Seth got second place in the fashion category for “The Skinny on Fashion,” March 20, 2006). I saw and cheered the news yesterday, but balked at the thought of finding and formatting the images in the middle of my own mag’s close, so hooray for the Times (typing that despite my rage at last Sunday’s book review), since they have a nice collage with two of the New Yorker covers and an article and so forth.

Why is this under “Seal Barks,” by the way? This category is for everything related to artwork in the magazine—spots, cartoons, covers, and other illustrations. If you click on the category names on the green bar above, you can trawl the archives for other items about artwork, or about the magazine’s editors-in-chief so far (“Eds.“). My and other contributors’ reviews of things related to but outside the magazine itself go under “Looked Into,” and for a veritable Katz’s Deli of links in further pursuit of the details in a New Yorker story go to “Eustace Google” (I love that illustration). I play favorites from the previous week’s magazine in “Pick of the Issue.”

“Ask the Librarians,” of course, is the deep research and sharp insight of the New Yorker librarians Jon Michaud and Erin Overbey, who answer the best questions sent in by Emdashes readers (here’s the email address to use) about the components (big and small) and personalities (famous and forgotten) of the magazine (past and present). “Headline Shooter,” which is also the name of a movie in which Robert Benchley played a radio announcer in 1933, is a quickie without commentary. In “On the Spot” either I or a trusted delegate (applications welcome) go to something New Yorker-related, like a reading, a talk, a gallery opening, a musical event, a play, &c., and report back. I also use “On the Spot” for announcing events I can’t go to, because they’re in Alaska or something. At parties I tend not to feel like taking notes, so you’ll have to rely on others for that sort of scuttlebutt.

The “Jonathans Are Illuminated” category concerns all Jonathans of letters, the ones you know well and the ones who have yet to leap into Bright Young Jonathanness; “X-Rea” tracks sightings (mine and yours!) of and inquiries into the famous typeface and the other work of original New Yorker team member Rea Irvin, whose name, as you can deduce from the category title, is pronounced Ray as in Sugar, not Ree as in readerly. In “Letters and Challenges” I provide challenges (with prizes!) and print your letters, but only the ones you’ve explicitly given me permission to print, since I don’t use mail without permission. I’m happy to print things anonymously, and often do, since many writers and critics who otherwise dream of being ubiquitously and inescapably in print would rather not be named on a blog, even if their letter concerns nothing scandalous or bridge-burning. And that’s OK with me. Finally, “Hit Parade” collects the posts that, for whatever reason, got people all whirled up like soft-serve ice cream.

Later, almost forgot: Here’s all my coverage (still ongoing, can you believe it?) of this year’s New Yorker Festival, and in Personal, you can read my Innermost Thoughts, or at least the ones I choose to share with The World. It’s where I get to be a blogeuse.

Ask the Librarians (III)

A column in which Jon Michaud and Erin Overbey, The New Yorker’s head librarians, answer your questions about the magazine’s past and present. E-mail your own questions for Jon and Erin; the column has now moved to The New Yorker‘s Back Issues blog. Illustration for Emdashes by Lara Tomlin.

Q. For the very first years of the magazine, how did the editors solicit pieces? Did they advertise anywhere?

Jon writes: Ben Yagoda notes in his book About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made that no fewer than 282 writers contributed at least one piece to The New Yorker in 1925, its first year of publication. This number illustrates how unsettled the magazine’s editorial staff was in its early life, but it may also be a little misleading. Many of those “pieces” were short Talk of the Town stories often no longer than a paragraph, sometimes written by relatives and friends of the magazine’s staff. The most significant group of early contributors to The New Yorker came from a circle of writers and artists who had known the magazine’s founding editor, Harold Ross, from his years at other magazines, including The Stars and Stripes, The Home Sector, and Judge. Many were also members of the Algonquin Round Table, as were Ross and his wife, Jane Grant. The list of contributors includes writers Alexander Woolcott, Ring Lardner, Corey Ford, Franklin P. Adams, Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, and Margaret Case Harriman, and artists John Held, Jr., and Gardner Rea.

There are two instances in which the magazine, in its early years, formally solicited work from a group of writers. In 1928, seeking to change the public perception of The New Yorker as solely a humor magazine, its literary editor, Katharine Angell, wrote letters to a number of fiction writers asking for “serious” short stories. Many of them, including Kay Boyle, Sally Benson, and Louise Bogan, submitted work that was later published. The next year, Angell wrote a similar letter soliciting work from poets.

From the beginning, editors at The New Yorker also made a habit of spotting talented young newspaper journalists and bringing them on board, first as freelancers and then as staff writers. A.J. Liebling and Joseph Mitchell are two notable early examples of this practice, which continues with writers such as Malcolm Gladwell and Michael Specter.

In 1923, when Ross first hatched the idea of a weekly humorous magazine with a focus on New York, he created a mock edition that he showed prospective contributors and backers. According to Thomas Kunkel’s Genius in Disguise: Harold Ross of The New Yorker, he carried the dummy around for two years, boring his friends with it. Kunkel notes that “even Woollcott…who could be counted on to vouch for Ross’s editorial acumen, was skeptical. He refused to introduce Ross to the influential publisher Condé Nast.” That union would take another sixty years.

Q. Which writer holds the record for the most short stories published in one year?

Erin writes: In earlier years, The New Yorker ran several fiction pieces in each issue; today, it usually runs one short story and one casual (now known as Shouts and Murmurs) per issue, excepting the two annual fiction issues, which often contain four or five fiction pieces. The writer with the record for the most short stories published in one year happens to be E. B. White, with an astounding twenty-eight stories published in 1927. James Thurber and the novelist John O’Hara follow closely behind White, both with twenty-three stories published in 1932 and 1929, respectively. Frank Sullivan, one of the magazine’s early humor writers, contributed twenty-two short stories in 1931, while noted fiction writer S. J. Perelman contributed fifteen in 1953.

The writer who has published the most short stories in the magazine overall is Thurber, who contributed two hundred and seventy-three fiction pieces from 1927 to 1961. Perelman is a close runner-up, with two hundred and seventy-two short stories published between 1930 and 1979. Other prolific New Yorker fiction writers include O’Hara (two hundred and twenty-seven in all), Sullivan (one hundred and ninety-two), White (one hundred and eighty-three), and John Updike (one hundred and sixty-eight).

Q. The New Yorker used to have a horse-racing column. Who wrote it? Were these racing columns ever collected in a book?

Jon writes: The New Yorker‘s horse-racing column, The Race Track, was written by George F. T. (George Francis Trafford) Ryall under the pen name Audax Minor. His first column for the magazine appeared in the July 10, 1926, issue, under the department heading The Ponies. After a few months it was renamed Paddock and Post before finally becoming The Race Track in May of 1927. The column ran regularly until December 18, 1978.

Ryall was born in Toronto and educated in England, and his family owned a string of racehorses. His first job was covering sports for the Exchange-Telegraph agency of London; he then wrote about horse racing for the New York World. While still at the World, Ryall started contributing to The New Yorker, using the pseudonym Audax Minor. (The nom de plume was a tribute to the British racing writer Arthur Fitzhardinge Berkeley Portman, who wrote under the name Audax Major.) Ryall contributed several Profiles to the magazine and also wrote about men’s fashion, automobiles, and polo, but he is most remembered for The Race Track. The columns were usually short (two pages at most) and crammed with information about horses, horse trainers, jockeys, stables, owners, tracks, touts, and every other facet of racing in the United States and Europe. Here is an example, from a 1977 column:

American-bred Alleged–he’s by Hoist the Flag out of Princess Pout–won the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe at Longchamp in Paris the other Sunday. He took it by a length and a half from Balmerino, the top horse in New Zealand and Australia. Crystal Palace, winner of the French Derby, was third, a head in front of Queen Elizabeth of England’s Dunfermline.

Accounts of races were interspersed with Ryall’s dry observations and efficient character sketches, such as this passage from a 1938 column about the trainer James Fitzsimmons:

He still suffers from the effects of an experiment he made years ago when, as a jockey, he wanted to reduce [his weight]. Someone told him that surplus weight could be baked off and, being a literal-minded man, Fitzsimmons found a brick kiln which was cooling out, crawled in, and lay for some hours on the floor. It was the end of him as a rider; the muscles of his shoulders, back, and neck have never recovered.

At the time of his death in 1979, Ryall was the writer of longest record at The New Yorker and, at 91, the oldest writer on staff. In his unsigned obituary in the magazine (October 22, 1979), Robert MacMillan noted the following: “Once in a while, our Checking Department, trying to verify some remote detail he had mentioned, would be told by outside sources that the only man alive who could answer that question was George Ryall of The New Yorker.”

Ryall’s work has never been collected in book form by a commercial publisher. Some of his pieces have appeared in anthologies of sports writing, but the best way to read his columns (there are more than a thousand of them) is via The Complete New Yorker.

Q. The magazine’s editorial positions have become visibly political in recent years; in fact, the first Talk of the Town piece (Comment) is usually political commentary. When did this start? Did the magazine, for example, take a collective position on the Vietnam War, as it has on Iraq?

Erin writes: The Comment page (or Notes and Comment, as it was originally known) has long been a place for the magazine to express an editorial viewpoint, political or otherwise. According to E. B. White, Scott Elledge’s 1984 biography of the writer credited with originating the Comment editorial, Harold Ross believed that the Comment “set the keynote for the magazine.” The earliest comments were a series of short opinion essays about newsworthy people and events in the city and around the country. Typically, they displayed a light, humorous touch, and many were not political at all.

Characteristic of these are a 1933 Comment by White on the Douglas Fairbanks-Mary Pickford divorce (“We call on Miss Pickford’s lawyer to amend his extremely prejudicial complaint by stating that Mr. Fairbanks’ penchant for travel merely destroyed the legitimate ends of matrimony for Miss Pickford”) and a 1940 Comment by Wolcott Gibbs about the disappearance of “Café Society.” (“Its members are anachronisms and they eat too much, but we shall miss them.”)

The early Comment writers (among them White, Gibbs, and Geoffrey T. Hellman) sometimes used the space to editorialize about–and poke fun at–not only America’s enemies, like Hitler and Mussolini, but also America’s leaders, including presidents and other politicians, business leaders, and the wealthy society elite. A 1937 Comment by White derided Franklin D. Roosevelt as an “Eagle Scout” who’d gotten out of hand, while a 1954 Comment (also by White) categorically dismissed Senator Joseph McCarthy as “the No. 1 waster of the nation’s time.” Early World War II editorial pieces began to take a slightly more serious tone, with prescient warnings against Nazism and Hitler.

It was in the sixties and seventies that the magazine became more overtly political in its editorials. Many Comments expressed disillusionment with both the Vietnam War and the political leadership in Washington. As early as 1965, a Comment by John Updike referred to the conflict in Vietnam as an “unfathomable impasto of blood and money and good intentions and jungle rot.” In 1969, William Shawn took the unusual step of running a long Comment consisting wholly of an anti-war speech by the Nobel Prize-winning scientist George Wald. “We are bombing them in Hanoi [our government tells us] so that we won’t have to fight them in the streets of San Francisco,” Shawn wrote in a 1972 Comment. “And in the course of…all this bombing, our souls have withered.”

Comment writers Jonathan Schell, Richard Goodwin, and Richard Harris wrote impassioned editorials on the growing chaos in Vietnam and the seeming inability of America’s leaders to resolve the conflict. “Somehow, the country has been more battered by this war than by any other war in the century,” Schell wrote in 1972. “It has devoured a generation of our young people, killing some and embittering others…. For ten years, death has had us in its grip, and now it is we…who are beginning to die.”

From the nineties to the present, senior editor Hendrik Hertzberg has succeeded White and Schell as the chief writer of the page, contributing between two and three Comments a month. His Comments on the Afghanistan War, in late 2001, were primarily positive, albeit with a prophetic warning, in December of that year, that “the struggle has begun well, but it has only begun.” With his Comments on the Iraq War–thirteen in all–Hertzberg has taken a more skeptical tone. As early as August of 2002, he wrote that the Bush Administration has “produced plenty of plans for war in Iraq…but it has not yet produced a rationale.” In the summer of 2003, after the war had officially ended, he stated that conditions in Iraq “are disastrous by the looser standards of places like Beirut, Bogota, and Bombay.” And in August 2006–a full four years after his first Comment on the war–he lambasted the failure of President Bush’s “gamble” in Iraq.

For more than 80 years, the magazine has continued to offer an editorial viewpoint during times of peace and war. In 1945, E. B. White remarked on the delicate role of writers and the free press during wartime: “We have been in a good position to observe the effect on writers and artists of war and trouble…. It is hard to remain seated on the low hammocks of satire and humor in the midst of grim events.”

Addressed elsewhere in Ask the Librarians: VII: Who were the fiction editors?, Shouts & Murmurs history, Sloan Wilson, international beats; VI: Letters to the editor, On and Off the Avenue, is the cartoon editor the same as the cover editor and the art editor?, audio versions of the magazine, Lois Long and Tables for Two, the cover strap; V: E. B. White’s newsbreaks, Garrison Keillor and the Grand Ole Opry, Harold Ross remembrances, whimsical pseudonyms, the classic boardroom cartoon; IV: Terrence Malick, Pierre Le-Tan, TV criticism, the magazine’s indexes, tiny drawings, Fantasticks follies; III: Early editors, short-story rankings, Audax Minor, Talk’s political stance; II: Robert Day cartoons, where New Yorker readers are, obscure departments, The Complete New Yorker, the birth of the TOC, the Second World War “pony edition”; I: A. J. Liebling, Spots, office typewriters, Trillin on food, the magazine’s first movie review, cartoon fact checking.

A Goldmine of Pauline Kael Reviews

Emily Gordon writes:

Just discovered this, here; it may even be the entirety of 5001 Nights, but I’ll have to look into that. Just because it’s a now-unsightly Geocities page (though there are far worse) doesn’t mean it doesn’t contain essential information. Like this, her review of Jaws (condensed from the long version in When the Lights Go Down:

Jaws

US (1975): Horror

124 min, Rated PG, Color, Available on videocassette and laserdiscIt may be the most cheerfully perverse scare movie ever made. Even while you’re convulsed with laughter you’re still apprehensive, because the editing rhythms are very tricky, and the shock images loom up huge, right on top of you. The film belongs to the pulpiest sci-fi monster-movie tradition, yet it stands some of the old conventions on their head. Though JAWS has more zest than an early Woody Allen picture, and a lot more electricity, it’s funny in a Woody Allen way. When the three protagonists are in their tiny boat, trying to find the shark that has been devouring people, you feel that Robert Shaw, the malevolent old shark hunter, is so manly that he wants to get them all killed; he’s so manly he’s homicidal. When Shaw begins showing off his wounds, the bookish ichthyologist, Richard Dreyfuss, strings along with him at first, and matches him scar for scar. But when the ichthyologist is outclassed in the number of scars he can exhibit, he opens his shirt, looks down at his hairy chest, and with a put-on artist’s grin says, “You see that? Right there? That was Mary Ellen Moffit-she broke my heart.” Shaw squeezes an empty beer can flat; Dreyfuss satirizes him by crumpling a Styrofoam cup. The director, Steven Spielberg, sets up bare-chested heroism as a joke and scores off it all through the movie. The third protagonist, acted by Roy Scheider, is a former New York City policeman who has just escaped the city dangers and found a haven as chief of police in the island community that is losing its swimmers; he doesn’t know one end of a boat from the other. But the fool on board isn’t the chief of police, or the bookman, either. It’s Shaw, the obsessively masculine fisherman, who thinks he’s got to prove himself by fighting the shark practically single-handed. The high point of the film’s humor is in our seeing Shaw get it; this nut Ahab, with his hypermasculine basso-profundo speeches, stands in for all the men who have to show they’re tougher than anybody. The shark’s cavernous jaws demonstrate how little his toughness finally adds up to. This primal-terror comedy quickly became one of the top-grossing films of all time. With Lorraine Gary; Murray Hamilton; Carl Gottlieb, who co-wrote the (uneven) script with Peter Benchley, as Meadows; and Benchley, whose best-seller novel the script was based on, as an interviewer. Cinematography by Bill Butler; editing by Verna Fields; music by John Williams. Produced by Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown, for Universal. (Spielberg didn’t direct the sequels-the 1978 JAWS 2, the 1983 JAWS 3-D, and the 1987 JAWS THE REVENGE.)

For a more extended discussion, see Pauline Kael’s book When the Lights Go Down.

Related on Emdashes:

Paulette Does Dallas

Anticipation (as Sung By Carly Simon)

Ask the Librarians (II)

A column in which Jon Michaud and Erin Overbey, The New Yorker’s head librarians, answer your questions about the magazine’s past and present. E-mail your own questions for Jon and Erin; the column has now moved to The New Yorker‘s Back Issues blog. Illustration for Emdashes by Lara Tomlin; other images are courtesy of The New Yorker.

Q. When did Robert Day start drawing for The New Yorker? For how long? How many drawings were published, and do you have a favorite?

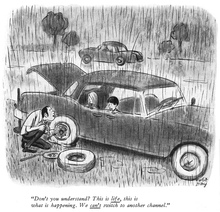

Erin writes: Robert Day, a longtime cartoonist and cover artist at the magazine, began contributing to The New Yorker in September of 1931. Prior to joining the magazine, Day had been a freelance cartoonist at the New York Herald Tribune. In a career at the magazine that spanned forty-five years, from 1931 to 1976, he published nearly eighteen hundred cartoons and eight covers. Many times, the prolific cartoonist had more than one cartoon in an issue. One of my favorite Day cartoons ran in the July 25, 1970, issue. In it, a father fixes a flat tire along a busy highway and says to his two young children, “Don’t you understand? This is life, this is what is happening. We can’t switch to another channel.” Day died in 1985, at the age of eighty-four. In the obituary The New Yorker ran after his death, former art editor Lee Lorenz wrote of Day: “His unadorned brush drawings, with their juicy, effortlessly flowing line, were as elegant as anything we have ever published.”

Q. What is the breakdown of The New Yorker‘s readership between New York and the rest of the world?

Jon writes: According to 2005 data from the Audit Bureau of Circulation, The New Yorker has 183,732 subscribers in the New York metropolitan area, representing 19 percent of its total circulation of 1,051,919. (Circulation includes both paid subscriptions and newsstand sales.) The New Yorker has 965,341 subscribers in the United States, 14,044 subscribers in Canada, and 20,453 subscribers in the rest of the world. The state with the most subscribers is California, with 177,814; the state with the fewest is South Dakota, with 723. The smallest market for The New Yorker in North America is the Yukon Territory, with seven subscribers. There are several countries–including Malawi, Brunei, the Dominican Republic, and Albania–with only one subscriber to the magazine. The current subscription rate is $52 domestic, $90 for Canada, and $112 for other countries.

In its early years, the magazine was not above poking fun at its own international subscription rates. A spoof in the October 2, 1926, issue took the form of a letter from a reader in Vevey, Switzerland, complaining about the cost of subscribing to The New Yorker ($7): “Do you know what I could get with seven whole American dollars over here? Merely (choice) six bottles of real Gordon gin…two pairs of natty sport shoes…two pairs of white flannel trousers, a return ticket to Paris…or the services of a gifted Swiss cook-waitress-chambermaid for almost one month.”

We don’t know what the going rate for domestic help in Switzerland is these days, but the price of an international subscription to The New Yorker will still buy six bottles of Gordon’s gin from a Manhattan liquor store ($18.99 per 1.75 liter bottle), a pair of Zoom LeBron IIIs from Nike ($110), one new pair of flannel pants from the Orvis catalog ($98), or a one-way second-class ticket on the TGV between Geneva and Paris (70 Euros or about $90, if purchased a month in advance).

Q. What are some departments that no longer exist? Did the magazine ever have regular, say, tennis or vaudeville reviews?

Erin writes: While certain departments–such as A Reporter at Large and The Current Cinema–have existed since the start of the magazine, many others have fallen out of fashion. In some cases, department titles have simply evolved over time. A few of my personal favorites of these extinct departments include That Was New York (1928-81), Of All Things (1925-51), and H. L. Mencken’s Days of Innocence (1941-43).

Other extinct departments are equally varied. Broadway Rackets (1927), a column by Jack Wynn, concerned mob rackets and scams operating in midtown Manhattan at the time. Speakeasy Nights (1927-29), by Niven Busch, Jr., reviewed Manhattan speakeasies during the Prohibition era. Ring Lardner’s Over the Waves (1932-33) discussed popular radio programs of the day. The Army Life (1941-44), by E. J. Kahn, was a chronicle of soldiers’ activities around the globe during the Second World War. And Notes for a Gazetteer (1959-66), written by Philip Hamburger, explored the cultures of various cities across the nation and was a sort of precursor to Calvin Trillin’s U.S. Journal.

The magazine also ran a regular Football column from 1926 to 1980 (written primarily by R. E. M. Whitaker), a Tennis Courts (or On the Courts) column from 1926 to 1947, and a Yachts and Yachtsmen column from 1927 to 1941. Other sports the magazine used to cover on a regular basis include boxing, horse racing, golf, rowing, polo, and hockey. About the House (1926-74), an interior-decorating column, and Lois Long’s Feminine Fashions (1926-82) round out an eclectic assortment of extinct departments.

Some departments that stop running in the magazine later reappear in a slightly different version: the Tables for Two restaurant column ran as a stand-alone column from 1926 to 1962, and then later re-emerged in the Goings On About Town section in 1995. Similarly, The Wayward Press (written primarily by A. J. Liebling) ran from 1927 to 1963, and was re-introduced in 1999 by Hendrik Hertzberg; and the Shouts & Murmurs “casual” (1929-34), which was originally written by Alexander Woollcott, reappeared in 1992.

Many of these extinct departments reflect a playful sensibility. What are we to make of department names like the Department of Correction, Amplification & Abuse, or the Department of Misquotation, Correction & Inter-Urban Relations? Equally droll are When New York Was Really Wicked (1927-28), Our Windswept Correspondents (1954), and A Reporter in Bed (1942-50). As I pored over the vast archive of departments, I wondered if any headings could have been left unaddressed. Apparently, there is at least one. According to The Years with Ross (1957), by James Thurber, Harold Ross once told Thurber that he’d “never run a department about dogs.”

Q. Are there plans to update The Complete New Yorker?

Jon writes: Yes. An update is just about to be released. It includes issues from February 2005 through the end of April 2006. The update, which comes in the form of a new disk 1 for the DVD set, costs $19.99 and is available from The New Yorker Store at www.newyorkerstore.com.

The update has been designed to integrate seamlessly with the first eighty years, and the user’s reading lists and notes will be preserved. In addition to providing fourteen months of additional issues, it features modifications and improvements to the archive’s search engine. The update will also be included on the portable hard drive version of The Complete New Yorker, which is being released on September 18.

Q. Why did it take so long for The New Yorker to get a table of contents?

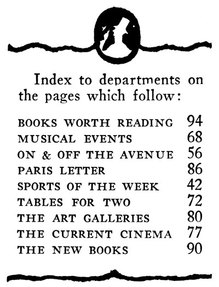

Erin writes: The New Yorker famously did not have a conventional table of contents until 1969. But the magazine actually started running a small index of articles or departments with the March 5, 1927, issue; it was originally located in the middle of each issue and later moved to the first page of the Goings On About Town section.

The first conventional T.O.C. ran in the March 22, 1969, issue. This version included all major departments, including fiction and poetry, and authors, as well as cover artists and cartoonists. According to Ben Yagoda’s book About Town (2000), when a longtime editor, Daniel Menaker, mentioned the new T.O.C. to a fact-checker at the magazine, the checker protested, “But now readers will know what’s in the magazine.”

In the April 18, 1988, issue, the magazine ran the first full-page T.O.C. with new type and layout; it was also the first T.O.C. to feature the current Eustace Tilley image above the index.

A greatly expanded T.O.C.–including titles, blurbs, and major illustrations and photographs as well as articles–debuted in the October 5, 1992, issue, which was then-editor Tina Brown’s first issue. The current T.O.C. was unveiled in the February 21 & 28, 2000, seventy-fifth anniversary issue, and it featured a new layout and red typeface for certain departments.

Q. During the Second World War, was there a special wartime edition of the magazine for soldiers?

Jon writes: From September 1943 through the end of 1946, The New Yorker produced a special overseas edition for the armed services, which was distributed free to soldiers by the Special Service Division of the U.S. Army. The “pony” edition, as it was known, began as a monthly, but became a weekly with the March 25, 1944, issue. Smaller in format than the regular magazine (its dimensions were 8 1/2 by 6 inches, and it usually ran to 26 pages), the pony New Yorker contained no advertising. It also omitted the Goings On About Town listings, and, with a few exceptions, movie, music, and theatre reviews. It did, however, replicate the typography and layout of the regular magazine. The entire Talk section was reproduced, along with numerous cartoons and a full page of Newsbreaks at the back. The pony also reprinted many longer pieces, including John Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” which appeared in its entirety.

Credit has been given to the pony edition for the expansion of The New Yorker‘s readership after the war. Writing in the December 28, 1946, issue, E. B. White noted that it was the last issue that would be reproduced in a pony edition:

As near as we can make out from reports that have come in, the pony New Yorker was a success. Held together by only one staple, it was a quick disintegrator, but its fugitive little pages were studied by homesick men and women all over the uncivilized world…. The small type was calculated to destroy what was left of a soldier’s vision; nevertheless, the pony was hungrily read–some copies by a dozen or more people. At one time, what with the copies of the regular edition mailed second-hand by soldiers’ families, our service readers outnumbered our civilian readers ten to one. Thank God that is no longer the case, and thank God for the reason why it isn’t.

Addressed elsewhere in Ask the Librarians: VII: Who were the fiction editors?, Shouts & Murmurs history, Sloan Wilson, international beats; VI: Letters to the editor, On and Off the Avenue, is the cartoon editor the same as the cover editor and the art editor?, audio versions of the magazine, Lois Long and Tables for Two, the cover strap; V: E. B. White’s newsbreaks, Garrison Keillor and the Grand Ole Opry, Harold Ross remembrances, whimsical pseudonyms, the classic boardroom cartoon; IV: Terrence Malick, Pierre Le-Tan, TV criticism, the magazine’s indexes, tiny drawings, Fantasticks follies; III: Early editors, short-story rankings, Audax Minor, Talk’s political stance; II: Robert Day cartoons, where New Yorker readers are, obscure departments, The Complete New Yorker, the birth of the TOC, the Second World War “pony edition”; I: A. J. Liebling, Spots, office typewriters, Trillin on food, the magazine’s first movie review, cartoon fact checking.

Ask the Librarians: The Debut

A column in which Jon Michaud and Erin Overbey, The New Yorker’s head librarians, answer your questions about the magazine’s past and present. E-mail your own questions for Jon and Erin; the column has now moved to The New Yorker‘s Back Issues blog. Illustration for Emdashes by Lara Tomlin.

Q. How and when did A.J. Liebling start writing for The New Yorker? Was it under his own name, or was it as an anonymous Talk of the Town reporter? Can one recognize his style from his early work in the magazine?

Jon writes: Liebling was hired by The New Yorker in 1935, when he was thirty years old. Prior to joining the magazine, he had worked as a newspaper reporter, most recently for The New York World-Telegram (where Joseph Mitchell was a colleague). During his last two years at the World-Telegram, Liebling had begun contributing freelance Talk of the Town stories to The New Yorker. His first (unbylined) story in the magazine was “Prosperity Pens,” in the January 7, 1933 issue, about a pyramid scheme involving the sale of fountain pens, wallets, and flashlights.

According to Raymond Sokolov’s biography, Wayward Reporter (Harper & Row; 1980), Liebling initially had some difficulty making the transition from newspaper journalism to the longer-form reporting practiced at The New Yorker. His first bylined piece was a three-part profile of the preacher Father Divine (June 13, 20, and 27, 1936), co-written with St. Clair McKelway. By then, Liebling had published more than twenty-five unbylined Talk stories. Because the Talk section was so heavily rewritten and edited at that time, it is difficult to make a comparison between Liebling’s mature style and his writing in these early pieces. It is not difficult, however, to notice that, from the beginning, Liebling was an omnivorous reporter. Among those early Talk stories are pieces on subjects as diverse as the Bronx County Motor Vehicle Bureau, the Ethiopian Consul General, a retired fireman who had become a parrot merchant, and the bell-ringer at Riverside Church. There were also several pieces about boxing, one of the numerous subjects Liebling would go on to write about with distinction during his thirty-year career at the magazine.

Q. Who does those little line drawings found throughout the magazine, and why is no credit ever given them? Have “spots” always been listed in the table of contents?

Erin writes: The “spot” drawings that run throughout the magazine have appeared in The New Yorker since the very first issue, in 1925. Initially, there were just a few spots in each issue. The drawings were small and often playful, and many were unsigned. From the 1940s onward, the spot illustrations appeared more frequently. Early spot illustrators included Victor De Pauw, Roger Duvoisin, H. O. Hofman, George Shellhase, Virginia Snedeker, Beatrice Tobias, Edward Umansky, and Garth Williams. Several artists known for their cartoons and covers–such as Constantin Alajalov and Abe Birnbaum–also contributed spot drawings.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, artists like Raymond Davidson, Pierre Le-Tan, Kenneth Mahood, Jenni Oliver, and Gretchen Dow Simpson all published spots in the magazine. During the 1900s and early 2000s, a stable of illustrators was used, and spots were sometimes rerun after six months or so. These artists include Laurent Cilluffo, Jacques De Loustal, Philippe Petit-Roulet, Emmanuel Pierre, Robert Risko, and Benoit Van Innis. Beginning with the February 14 & 21, 2005 issue, the magazine began running credited spots by a single artist. In April 2005, spots started being listed in the Table of Contents.

Q. When was the last typewriter spotted in the office?

Jon writes: Today. There are three typewriters in the library (two IBM Wheelwriters and a Brother ML 300). Though the majority of our work is done on computers–and has been for some time now–there are still a few archival resources we maintain with typewriters. We’re the only department in the office that still uses typewriters on a regular basis.

Q. When did Calvin Trillin start writing food pieces? How many different kinds of cuisine has he covered?

Erin writes: Calvin Trillin has had a long career at The New Yorker, writing about subjects as diverse as the civil rights movement (“An Education in Georgia,” 7/13/63), female coal miners in Pennsylvania (“Called at Rushton,” 11/12/79), a tick-tack-toe-playing chicken in Chinatown (“The Chicken Vanishes,” 2/8/99), and the death of a U.S. soldier in Iraq (“Lost Son,” 3/14/05). The first lengthy food piece he wrote for the magazine was a U.S. Journal article, “Eating Crawfish” (5/20/72), about the Crawfish Festival in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana. He has contributed a total of forty-four food pieces to the magazine. Many of these pieces ran as U.S. Journals and focused on regional American cuisines, such as New England clambakes (1978), Little Italy’s San Gennaro festival (1981), catfish eating in Florida (1982), and barbecue contests in Memphis (1985). Trillin published twenty-one of these food-centered U.S. Journals from 1972 to 1982.

Beginning in 1982, Trillin also published seven pieces on foreign cuisines, including those from Hong Kong, Ecuador, and France. From the 1980s to the present, many of his food pieces have run under the department headings of Our Far-Flung Correspondents, American Chronicles, and Annals of Gastronomy. Other culinary topics he has covered include pizza baron Larry (Fats) Goldberg (1971 and 1987), oyster eating in Delaware (1980), Arthur Bryant’s restaurant in Kansas City (1983), Haagen-Dazs’s and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream (1985), Chinatown restaurants (1986), Manhattan bagels (2000), Cajun boudin sausage (2002), Shopsin’s café in Greenwich Village (2002), and San Francisco takeout (2003).

Q. What’s the first movie The New Yorker ever reviewed? How many movie critics have there been at the magazine, and who are they?

Jon writes: The first movie reviewed by The New Yorker was F.W. Murnau’s silent The Last Laugh (Der Letzte Mann), starring Emil Jannings. The review, by Will Hays, Jr., appeared in the first issue of the magazine–February 21, 1925–in a column of criticism and celebrity gossip called “Moving Pictures.” Hays deemed the movie “a superb adventure into new phases of film direction…a splendid production.”

Hays wrote only three more movie columns for the magazine. Over the next few years, the column was written by Theodore Shane (signed T.S.) and Oliver Claxton (O.C.). It also sometimes ran unsigned. The first long-term reviewer, John C. Mosher, took over in 1928 and held the post until 1942. Thereafter, the magazine’s movie critics were: David Lardner (1942-44), John McCarten (1945-1960), Brendan Gill (1960-68), Roger Angell (1960-61 and 1979-80), Penelope Gilliatt (1967-1979), Pauline Kael (1967-1991), Terrence Rafferty (1988-1997), Anthony Lane (1993-present), Daphne Merkin (1997-1998) and David Denby (1998-present).

When the regulars were away, or when the magazine was between longer-tenured reviewers, a great variety of writers filled in. The list includes E.B. White, Wolcott Gibbs, John Lardner, Philip Hamburger, Edith Oliver, Whitney Balliett, Susan Lardner, Renata Adler, Veronica Geng, and Michael Sragow.

Q. Are cartoons fact-checked? What’s the

sort of thing that checkers ask to be changed in a drawing or caption?

Erin writes: Every cartoon is fact-checked for accuracy and also checked against the library’s archive to make sure that a similar cartoon has not run previously in the magazine. The New Yorker fact-checking department verifies both visual and text accuracy of a particular cartoon: If a drawing of the White House has the wrong number of columns on it or if a man’s coat is buttoned on the wrong side, then the fact-checking department informs the cartoon department of the discrepancy. The cartoon department will then either make the change or not depending on whether the discrepancy is intentional or not. In addition, if a cartoon caption gets a proper name wrong or, say, locates the Nôtre Dame in Bangkok, the fact-checking department will point out these inaccuracies. The cartoonists have learned that even a detail as small as the number on a taxicab will be checked to make sure it does not represent an actual cab number.

Addressed elsewhere in Ask the Librarians: VII: Who were the fiction editors?, Shouts & Murmurs history, Sloan Wilson, international beats; VI: Letters to the editor, On and Off the Avenue, is the cartoon editor the same as the cover editor and the art editor?, audio versions of the magazine, Lois Long and Tables for Two, the cover strap; V: E. B. White’s newsbreaks, Garrison Keillor and the Grand Ole Opry, Harold Ross remembrances, whimsical pseudonyms, the classic boardroom cartoon; IV: Terrence Malick, Pierre Le-Tan, TV criticism, the magazine’s indexes, tiny drawings, Fantasticks follies; III: Early editors, short-story rankings, Audax Minor, Talk’s political stance; II: Robert Day cartoons, where New Yorker readers are, obscure departments, The Complete New Yorker, the birth of the TOC, the Second World War “pony edition”; I: A. J. Liebling, Spots, office typewriters, Trillin on food, the magazine’s first movie review, cartoon fact checking.

Eustace Google, Guest Edition

Here’s a woman after my own heart: Sue Blank (great name; hope she’s a crossword fanatic) from the Newtown Advance. She’s saved me the googling I was planning to do for you nice people to uncover the obscure—to us philistines, that is—words in “Burning the Brush Pile,” Galway Kinnell’s lovely recent New Yorker poem about the sad end, or should that be ends, of a snake caught in a brush-pile fire. Here are the lines in question, with boldface for emphasis. Obviously, you need to read the whole poem to get the whole story, along with the rest of his poems, for general gladness.

…stumps, broken boards, vines, crambles.

Suddenly the great loaded shinicle roared

into flames that leapt up sixty, seventy feet,

In the evening, when the fire had faded,

I was raking black clarts out of the smoking dirt,

and a tine of my rake snagged on a large lump.

Then the snake zipped in its tongue

and hirpled away…

Detective Blank writes:

Once I wrote for a trade magazine that limited the length of my sentences to 20 words, the better to avoid challenging the ability of its readers. Many magazines and newspapers limit both vocabulary and sentence complexity to make content easily accessible to the average person. But having been a reader for more than threescore years, I rarely find a word in such magazines or newspapers whose meaning I don’t already know. When I do, I write it down and learn it. Then I keep it in my desk drawer where I can review it frequently until I’m sure I own it.

Thus a poem in the June 19 issue of The New Yorker gladdened my heart with four unfamiliar words: “clart,” “crambles,” “shinicle” and “hirple.” I went looking for definitions. The first word, clart, means to daub, smear or spread with mud, and as a noun, refers to a glob of mud. Shinicle refers to a fire and its light, and hirple means to hobble or limp. “Crambles” did not appear anywhere except in a slang dictionary, and the definition there did not fit. [I looked briefly, too; the sense I found is also “to hobble.”] Still, one can guess from context. The poem spoke of a bonfire built of boughs, stumps, broken boards, vines and crambles. So – perhaps “useless waste or clutter”? “Junk”?

Looking for definitions can easily lead us word freaks far astray, using up an hour or so in random explorations of unfamiliar words. While searching for “crambles,” I serendipitously found “whingle,” to complain, and it reminded me of “whinge,” a word I’ve heard used only by Englishmen to refer to a kind of whining complaint. Surely the two words derive from the same source.

Other useful words, lost, alas, to daily use, include… (cont’d.)

I once consulted on the choice of a single word in one of Galway’s poems while I was his student, and it also ended up in The New Yorker. Alice Quinn does not know of my contribution, since, really, it was so small. But, like the icebox plum, so sweet.

The first person to write in with a plausible (documented) definition of “cramble” as used in “Burning the Brush Pile” gets a prize—any Galway Kinnell collection, your choice.