Jonathan Taylor writes:

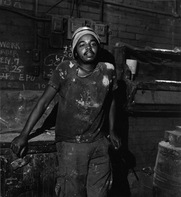

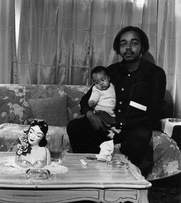

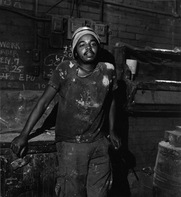

Milton Rogovin, aptly described on his website as “social documentary photographer,” died in January at age 101. A Buffalo optometrist, he was denounced as the city’s “Top Red” in 1957, and subsequently began photographing working people and the worlds that made them and that they made, in Buffalo and across the globe. For me, the series that stand out are Lower West Side Triptychs, photos of the same residents of that Buffalo neighborhood taken in 1972, 1984 and 1992, and Working People, described here by JoAnn Wypijewski, whose writings accompanied some of Rogovin’s publications:

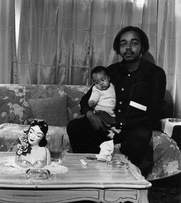

From 1977 to 1980 Rogovin photographed Buffalo’s working people: two shots of each subject, one at work and one at home…. They are marvelously evocative pictures, chiefly because Rogovin asks his subjects to compose their own portraits. A steelworker may look saucy and conquering on the job; matronly and just a little anxious at home with her kids. An odd-job man may express nonchalance, even a touch of scorn, in the plant; while, seated before a tableau of religious icons, commercial calendars and his own “work” photo, a curious mix of defensiveness and melancholy. You can’t type these people, because each time you return to them, they may disclose a new story.

This passage appeared in a Nation review of Verlyn Klinkenborg’s The Last Fine Time, a portrait of Buffalo’s East Side through the windows of a local bar. Wypijewski, an East Side native, continues, “But Klinkenborg’s people are mute, and their silence accomplishes that other end of romanticism: the annulment of history.” It’s not just a monumental takedown, it’s a stunning throwdown over the turning of social history into “creative writing” for an audience of “the explaining classes.” (Fortunately, it’s online here.)

Wypijewski first dismantles the cliche of Buffalo’s snow: “From the first words of the prologue Klinkenborg disqualifies himself as Buffalo’s biographer. ‘Snow begins as a rumor in Buffalo, New York.’ Snow—the cheap association every amateur joker makes with Buffalo? Rumor—the hint of subterranean preoccupation? Nothing bores Buffalonians I know more than the ready equation of the city with snow-storms; and nothing is approached with more equanimity than those same snowstorms.” But her critique is much deeper:

The book is meant to be an homage to the soul of the old East Side. Klinkenborg catalogues its citizens by occupation, from dressmaker to steamfitter, foundryman to church keeper; and even by name, eight lines of lyrical consonant combinations, with a few Germans thrown in to break up the meter. But even in homage—in fact, because of it—the people are lost, the center becomes the periphery. As romanticist, Klinkenborg is the medium through which the working class can be seen, and the picture he draws—an emotional yet guarded people, brightly striving but always just a bit behind the eight ball of life—is stylized in a way coincident with accepted notions….

….Charitably, I would say that Klinkenborg wrote this book out of love for his father-in-law, and the same reason I was glad not to know the real views of my relatives who baited me about politics may have impelled Klinkenborg to walk only on the safe side of history’s street. The result, though, is that Eddie—and by extension Buffalo—serves simply as a prop for Klinkenborg’s writing, and once the bar is sold and Eddie moves out to the suburbs it is as if he has no meaning except in tragedy. Klinkenborg has got his story.

The review even led to a public debate at Erie Community College between Wypijewski, Klinkenborg and several others. (The Buffalo News reported that Klinkenborg “kept his composure throughout the evening and said it was all part of a learning process.”)

I haven’t even read The Last Fine Time, so I can’t even comment on Wypijewski’s fairness. But it’s undoubtledly an essay that only grows in stature as the book recedes into the past. It’s sad how hard it is to imagine a struggle over art and social history being waged so prominently today on the terrain Wypijewski staked out (though Noreen Malone’s warning against enthusiasm for photography of Detroit’s ruins is a faint echo—and one still richocheting among the explainers).

Even harder, of course, is to imagine what you see before your lyin’ eyes in many of Rogovin’s pictures: “a middle class that included blue collar workers who were able to support their families on a single income,” in the words of Roy Edroso, taking on another would-be representer of a fantasized working class—to whom Rogovin’s photos are an enduring rebuke.

Wypijewski remembers Rogovin both in The Nation and at Counterpunch. And Klinkenborg does, too, at the Times.