Martin Schneider writes:

On Monday, November 15, one of the season’s most anticipated literary events will take place at 92nd Street Y. Jonathan Franzen, author of The Corrections and Freedom, and Lorrie Moore, author of A Gate at the Stairs and several other widely adored novels and story collections, appear together for a reading of their most recent works.

The event is at 8pm. Not surprisingly, spacious Kaufmann Concert Hall is already sold out. However, fans of Franzen and Moore can watch the proceedings live on the Internet by clicking on the above link.

I am fortunate to have a ticket—expect a report from me after the event.

Category Archives: On the Spot

Calvin Trillin and Adam Gopnik at 92Y

Martin Schneider writes:

I’m back in New York after a few months in Cleveland, Ohio (which I vastly enjoyed); one of the consolations of my return to the East Coast is the ability to visit New York’s indomitable cultural center, 92nd Street Y.

On Sunday, November 7, I went to see Calvin Trillin and Adam Gopnik discuss “The Writing Life” in Buttenwieser Hall on the second floor. The two writers, both closely associated with The New Yorker, opted (for the most part) to jettison the given theme and trade anecdotes about Manhattan and their shared Jewish heritage, which was fine by me.

Though they were billed as equals, Gopnik subtly played moderator to Trillin’s guest, giving Trillin a chance to spin some entertaining yarns—and intermittently to return the favor. As Trillin is something of a national treasure, this seemed only sensible. The session resists chronological narration but did yield a good many gems.

Trillin was wearing a handsome blue tie with red buffalo (pl.) on it, which he described as his “tribute to Carl Paladino.”

Apparently both men trace their ancestry to Ukraine. Gopnik’s forebears went to Canada via Ellis Island, whereas Trillin’s grandfather entered elsewhere: “We wouldn’t have anything to do with Ellis Island, so we went to Galveston.” Trillin spoke of the Galveston Movement, a pre-WWI project designed to bring Russian Jews to the American heartland. With a proviso: the newly arrived Jews were barred from staying in Galveston itself: “My family did not come here on a wave of acclamation.” So they moved to Missouri: St. Joseph and later Kansas City.

Trillin cited an article—was it in a MoMA publication?—that purported to establish that all those stories you hear about people’s names being changed by helpful and ignorant Ellis Island staff are false! I’d love to read more about this—if anyone knows of the article, please post a comment.

Trillin described his own childhood as “Leave It to Beaver as played by a troupe that had just completed a run of Fiddler on the Roof.”

Both Trillin and Gopnik grew up rooting for baseball teams that no longer exist: the Kansas City Blues and the Montreal Expos, respectively. Most of our audience, including myself, will presumably have a better command of the details of the latter organization.

During the QA section, an audience member asked the two writers to name a favorite piece they had written. Trillin named “Remembrance of Moderates Past” (3/21/77 issue), written on the occasion of the Carter administration’s arrival in Washington, D.C. (Gopnik’s favorite Trillin piece, by the way, is “Buying and Selling Along Route 1,” from the 11/15/69 issue.) Gopnik’s favorite piece of his own is “Angels Dining at the Ritz,” one of the late chapters in Paris to the Moon, but I haven’t established if or when that appeared in The New Yorker.

There was much more in the way of witty repartee, but my energies flag. Watch this space for more on 92Y events past and future.

Feisal Abdul Rauf to Appear at 92Y Debate

Martin Schneider writes:

On Sunday, December 5, at 4:30pm, 92Y is hosting a discussion titled, “Can We Understand Each Other? An Interfaith Dialogue.” Tickets are available to purchase—act quickly, because this event should sell out soon.

Participants will include Rev. Dr. Joan Brown Campbell, director of religion at Chautauqua Institution; Sister Joan Chittister, OSB, author of more than 27 books on issues involving women in church and society, human rights, peace and justice; Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, founder and CEO of the American Society for Muslim Advancement and architect of the Cordoba Initiative, an interreligious blueprint for improving relations between the Muslim world and the United States; and Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, associate of the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership.

Feisal Abdul Rauf is best known, of course, as the man behind the so-called “9-11 Mosque,” otherwise known as Park51, which has garnered an enormous amount of controversy in recent months.

For a taste of what this event might be like, check out This Week‘s debate from this past weekend, “Should Americans Fear Islam?” which included Rauf’s eloquent wife, Daisy Khan, and a host of other lively personalities.

Rauf has not made many public appearances during this controversy, making this event all the more exceptional.

It’s worth pointing out that the event is taking place on the Upper East Side, which is a Tea Party-approved distance from Ground Zero, according to many prominent Republican and conservatives who have objected to the Park51 plan.

Tonight at 92nd Street Y: Lydia Davis & ‘Madame Bovary’

Jonathan Taylor writes:

Tonight in New York City at 8:00, 92 Street Y hosts Lydia Davis for “An Evening of Madame Bovary.”

Kathryn Harrison’s Times review of Davis’s new translation of Madame Bovary makes a great case for (re)reading the novel, but doesn’t really flesh out why Harrison finds Davis’s translation choices so convincing. “Faithful to the style of the original, but not to the point of slavishness, Davis’s effort is transparent,” she writes, but that only raises questions of the sort the translator herself will probably address tonight.

Davis is not only a translator of Flaubert, but a fellow novelist (something often overlooked in the attention to her distinctive short fiction), who, within her essential novel The End of the Story, writes about the process of constructing a novel with the something like the meticulousness of Flaubert’s that Harrison describes. A good recent interview by the Rumpus does justice to The End of the Story.

Tonight, on the High Line, Free: Remedial NYC Food History

Jonathan Taylor writes:

As much as the High Line is everybody’s favorite example of well-designed adaptive reuse of abandoned industrial infrastructure, it’s amazing that, in an age of endless food jabber, the story of the High Line’s role in feeding New York is not more talked-about. Perhaps it’s because it belongs to the golden age of food industrialization, and goes against the grain of a preferred “artisanal” gastronomic past. (Click on image to see Father Knickerbocker devouring rail cars in 1938.)

But as food historian Rachel Laudan explains in a wonderful article, projecting such reigning preferences onto the past distorts it. And a free talk to be given on the High Line tonight by Patrick Ciccone should shed some needed light onto the scale and complexity of the food systems that it has taken to sustain a major metropolis, not just one’s own kitchen table.

It’s tonight at 6:30, in the Chelsea Market Passage section of the High Line, between 15th and 16th Sts.

Hysteria, Histrionics, Hypocrisy: The Theater of Thomas Bernhard Comes to New York City

Jonathan Taylor writes:

I’ve traveled to Thomas Bernhard’s house and met his half-brother, and organized a reading and a panel discussion on him. But I, like most readers of Bernhard on this side of the Atlantic, have never seen any of his plays performed. However, in his native Austria, Bernhard’s status derived at least as much from his theatrical work (and behavior) as it did on his novels and other prose. As a young man, he himself trained as an actor, and his assaults on the Austrian state and cultural overclass were primarily acted out, as it were, on the stage, culminating in the 1988 furor over his “Heldenplatz” at Vienna’s Burgtheater.

I’ll be seeing my first Bernhard play in a couple weeks, when the Toronto-based One Little Goat theater company, directed by Adam Seelig, brings its production of Bernhard’s 1986 play “Ritter, Dene, Voss,” to New York’s La MaMa E.T.C., from September 23 to October 10 (tickets here). I spoke with Seelig recently about “Ritter, Dene, Voss,” and how this play’s metatheatrical twist is the perfect vehicle for One Little Goat’s mission of developing what it calls a “poetic theater.”

The play is set in the Viennese mansion where the two Worringer sisters, wealthy dilettante actresses, live, and where they have brought home their brother Ludwig from the Steinhof mental hospital. The title of the play is composed of the names of the prominent German actors who are specified in the text as the players of the three roles: Ilse Ritter, Kirsten Dene and Gert Voss.

The character Ludwig is, not for the first time in Bernhard’s oeuvre, loosely based on characteristics of Ludwig Wittgenstein and his brother Paul. It’s a bit as if, say, Harold Pinter had written a play called, I don’t know, “Gielgud, Ashcroft, Redgrave,” with Gielgud playing the part of, who—Bertrand Russell maybe?

The One Little Goat production, which has been seen in Toronto and Chicago, does not star Ritter, Dene, or Voss, and avoids any futile attempt to incorporate or transmit the associations they would carry to Austrians. (Seelig notes that he has avoided seeing any rendition of the original production, directed by Bernhard’s frequent collaborator, Claus Peymann.) The La MaMa production stars Maev Beaty, Shannon Perreault and Jordan Pettle, and Seelig says he would willingly retitle the play in his production after them, if it were permitted.

JT: How did you first become aware of Bernhard and “Ritter, Dene, Voss”?

AS: I knew Bernhard the way you and so many others know Bernhard, as a novelist. I was familiar with some of the novels, I admired the writing, [and learned that] he was equally a playwright, that he virtually alternated between novels and plays. And as someone who directs plays, I started to examine them. What caught my attention immediately is the unpunctuated text, and the lack of, or at least the sparse, stage directions. In other words, this is a perfect fit for the kind of work I’m developing with One Little Goat, which we’re calling poetic theater. And what that means is, text that can be treated as a score, highly interpretive plays—plays that actors can seriously dig into and make choices, while still holding on to the possibility for multiple interpretation, and the ambiguity that poetry is capable of, and theater so often is not.

JT: Does your poetic theater approach depend on producing plays that lend themselves to it in the way they are written, or can it be a way of approaching just any old play?

AS: That’s a good question. The honest answer is, I don’t know. A better effort at the answer is that, to begin with, it’s wonderful to work with texts where the writer places a great deal of trust in the performers…. This is the perfect play for it, right? As you know, from the note Bernhard wrote [at the end of the play]: “Ritter, Dene, Voss intelligent actors.” So this is a play that writes up to the actors, as it were, as opposed to one that traps them in a kind of hard mask. If you will, the mask here is a soft mask.

And I think it would be a bit of a battle to take one of those, any old play as you say, and try to tone down the character in order for the actor to come through a little more. It would be more of a challenge, although, hey, it would be fantastic to try that.

JT: That’s interesting what you say about the respect for the actor, because there’s also a way that it struck me that Bernhard, by naming the actors, is kind of singling them out and toying with them. It certainly highlights the relationship of the author to the actors and the characters, alongside that between the actors and the characters.

AS: On the one hand, it’s extraordinarily respectful of the actors….he’s giving them a great deal of freedom. On the other hand, I think he is deliberately challenging them to negotiate an extraordinarily challenging text. It has, believe me, we’re finding a great deal of pleasure doing it, but yes, there are moments when you say, “Fuck you, Thomas Bernhard! You’ve deliberately made that hard on us.” And that is a form of—it’s not just a hagiography of the actors, it’s a form of tough love, and it hurts some times.

The whole premise of the play is a deliberate challenge. On the one hand, this play is seriously “entertaining.” This is the thing that Bernhard really understood. He uses it pejoratively in the play, but the phrase “world of entertainment” comes out; he understood that this is a world of entertainment, and so the play, he writes it with some very high stakes. In that sense it’s really Drama 101: What’s going to happen? There is suspense in terms of what’s going to happen, how is the brother, if at all, going to be reintegrated into the family, and what’s that going to cause? So you have the standard, someone-is-going-to-come plot scenario. You have the status quo, the two sisters live together, and the brother comes in and upsets it…. But in Bernhard’s case it’s also anti-theater, because there’s a reference in the play to this maybe being the 18th or 19th time that they’ve tried to do this!

JT: Are there particular junctures of the play that illustrate how you carry out your approach in this particular production?

AS: There are a few key moments, that I don’t want to reveal, to be honest. But generally speaking, it’s not so much a matter of our method. It’s much more a matter of casting. If you switch out one actor in this play, it will be an entirely different play. And that’s the kind of play that this is. Even if these actors tried to put up the most farcical of masks, the hardest of masks, the most ironclad of characters as it were, it would still be a totally different play every time you change the actors. So it’s a much more global thing, it’s not like, moment to moment we have a certain method…. And so I do want to turn attention to these actors, I mean I have three phenomenal actors, whose play it is—it’s their play.

That may not be such huge news, but I think a lot of people have been treating theater as if the play is distinct from the people who perform it. And I think that Bernhard is really clearly calling our attention to it by naming the actors for whom he wrote.

JT: You’ve written that this play’s “central subject, ultimately, is the art of acting. The two Worringer sisters, after all, are actresses, making Bernhard’s play a meta-play that simultaneously shows and addresses the machinations of theatremaking.” Can you tell me a little more about how Bernhard treats the theater as his subject?

AS: With Bernhard, one of the biggest words across the board, in both novels and plays, is “hypocrisy,” and theater is—and I mean this in the most loving way—a hypocritical art form. Every fiction that we create has its share of hypocrisy, because we are taking sincere feelings, sincere emotions, sincere actions, between each other on stage, and we’re manipulating them and tweaking them for dramatic purposes. So we’re taking our truth, an we’re messing with it. So I think that Bernhard, he understands how performers operate, how the theater operates, so brilliantly, so clearly, that he calls out that very hypocrisy, and that kind of covenant that’s sealed between the actors and the audience—that we all buy into the fiction.

Ben Greenman Reads in Brooklyn on Monday 6/21 and It Will be Awesome

Martin Schneider writes:

Get on over to Brooklyn’s Greenlight Bookstore at 686 Fulton Street (at S. Portland, in Fort Greene) this coming Monday, June 21, at 7:30 pm, when Ben Greenman will read from his new epistolatory story collection What He’s Poised To Do, published by Harper Perennial. It’s a Facebook event, too, which makes it even easier to remember to move it to the top of your queue. We’re just about to launch a fun giveaway for Greenman’s book later this afternoon, so watch for that!

From the Facebook description:

The author Ben Greenman celebrates the publication of his new collection of stories, “What He’s Poised To Do” (Harper Perennial) and its sister blog, Letters With Character. There will also be brief readings by Jonny Diamond (of The L Magazine); the actress and performance artist Okwui Okpokwasili (representing Significant Objects); Nicki Pombier Berger (representing Underwater New York); and Todd Zuniga (representing Opium Magazine, and appearing via Transatlantic technology).

I don’t know the witty New Yorker writer and editor personally, but I’ve had the pleasure of attending a few New Yorker Festival events that he moderated (one was with Ian Hunter and Graham Parker, another was with Yo La Tengo; there were others), and he always made an extremely positive impression on me—intelligent, funny, generous, self-deprecating, all the good things. Emily tells me that based on her having gotten to meet him in person at a recent Happy Ending event, my impressions are rock-solid.

I’m in the wrong city (Cleveland) at the moment to attend this event, but New Yorkers should get right on this.

Remnick and Coates: Video

Martin Schneider writes:

A couple of weeks ago Emily, Jonathan, and I attended an event at the New York Public Library with David Remnick and Ta-Nehisi Coates. I wrote about it here. The New York Public Library has posted a video of the event here.

That event was pegged to the publication of Remnick’s new book about Barack Obama, The Bridge. In line with that fact, Remnick has recently appeared on The Daily Show and Real Time with Bill Maher. The Daily Show‘s website has video here; HBO, which airs Real Time, doesn’t let you see video for free, but a free audio podcast of all telecasts is available on iTunes.

In the Daily Show appearance, Remnick called Jon Stewart a “sweetie pie,” and Stewart confessed to an unhealthy obsession with The New Yorker‘s weekly caption contest. The two men briefly discussed Barry Blitt’s originally notorious and now merely legendary cover featuring Michelle and Barack Obama from July 2008. Remnick remarked that The Daily Show “saved our bacon” on that particular subject. It’s well worth checking out Stewart’s coverage of that furor, to recall both the truly ridiculous (and apparently unanimous) condemnations The New Yorker received from the cable news outlets and Stewart’s own bottomless sensibleness.

Bluegrass, Matt Diffee, Mark Singer, Zachary Kanin: This Sunday in NYC!

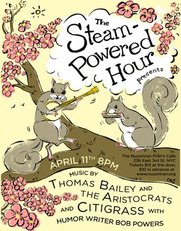

Emily Gordon writes:

The Steam-Powered Hour is one of the best variety shows going in New York. The combination of high-quality bluegrass, New Yorker cartoonists like Drew Dernavich, Carolita Johnson (who drew the merrily sciurine poster above) and Emily Flake drawing live on stage, comedy, storytelling, and spontaneous mass acoustic jams make it a hootenanny-salon you have to experience, trust me.

It’s a monthly party, but it’s taking a break for the summer, so make sure to come to the next two! Especially this one, because Citigrass are some of the rousingest, rollickingest pickers I’ve ever had the pleasure of hearing.

From the Steamers’ latest email:

In April, The Steam Powered Hour welcomes back Citigrass, winners of this year’s Battle of the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Bands. Also, more bluegrass goodness with Thomas Bailey and the Aristocrats, a story by The New Yorker staff writer Mark Singer and cartoonist Zachary Kanin. Plus, plenty more surprises. Hosted as usual by New Yorker cartoonist Matt Diffee.

April 11th, 8pm

Nuyorican Poet’s Cafe

236 East 3rd Street Between Ave B & C

New York City

Tickets are $15 at the door. Get ’em for $10 in advance at http://www.nuyorican.org.

You can follow The Steam Powered Hour on Twitter and on Facebook.

Report: Remnick and Coates, at the New York Public Library

Martin Schneider writes:

On Tuesday, April 6, I joined my Emdashes colleagues Emily Gordon and Jonathan Taylor at the New York Public Library for the publication day event for The Bridge, David Remnick’s eagerly awaited book about Barack Hussein Obama, the 44th President of the United States. It was an hour of spirited discussion about Obama, moderated by Atlantic Monthly blogger Ta-Nehisi Coates, who has written two articles for The New Yorker and also appeared as a panelist at the 2008 New Yorker Festival.

In the summer of 2008, Remnick and New Yorker executive editor Dorothy Wickenden entered into a wager about the election’s outcome—Remnick’s full explanation of his pessimism was a slow repetition of Obama’s full name. Today, as Remnick rightly says, nobody thinks much about that “Hussein.”

Remnick is so eloquent that I think we may have to invent a new word to describe him. Let me explain. When one listens to Remnick speak, he is so effortlessly precise and profound that one almost wants to use the word “glib”—but, of course, that word implies a want of substance, and nothing could be further from the truth. Is there a word for someone who appears to be glib but in fact is supplying all manner of valuable insight and even profundity? I don’t know, but we need one.

I’ve seen Remnick speak before, but always as the interviewer or moderator, never as the subject. Emily afterward pointed out how easily Remnick took to the role, comfortably reminiscing about his suburban New Jersey upbringing, in a household where radicalism was defined as “sitting too close to the TV set.” In short, a more personal Remnick.

The banter between Remnick and Coates was very amusing—much was made of their offstage editor-contributor relationship. For me, the funniest moment of all came during the Q&A section, when Paul Holdengräber,Director of Public Programs at the NYPL, asked Remnick about “that famous New Yorker cover,” obviously a reference to Barry Blitt’s “notorious” July 21, 2008, cover depicting Barack and Michelle Obama after having converted the Oval Office into a den of Islamist Black Power. Remnick: “The one with the bowl of fruit? The one with the abandoned summer house with the clothesline going across?”

Remnick’s take on the cover was, as always, astute: “I think it’s fair to say that not everybody liked it …. I was surprised at the scale of the not-everybody-liking-it.” It’s a lovely irony that Remnick, of all people, so convinced that the key to Obama’s undoing lay in his middle name, would be the editor to approve that cover. But of course, Remnick’s responsibility was not to ensure Obama’s election. And, in my view—as unpleasant as it must have been for Remnick to be hectored on live TV by the likes of Wolf Blitzer, who noted, with characteristic subtlety, “This could have been on the cover of a Nazi magazine!”—it was an entirely worthwhile gamble. (Remnick, for his part, drily noted that he hoped his mother was not watching CNN that particular day.)

To this day, Coates objects to the cover, on the grounds that the cover showed the right-wing conspiracists’ worst fears as “not ridiculous.” But of course, that is precisely what it did, it rendered them ridiculous. You couldn’t ponder that cover for very long without all of the scary right-wing premises seeming preposterous. I quote Art Spiegelman to that effect here, and contribute my own thoughts here. It may have been in a stealthy way, but Blitt’s cover, if anything, probably helped Obama just a little bit.

It’s impossible to discuss the meaning of President Obama without discussing race, and when the moderator is a black man who has written a memoir that would appear to be a bit similar to Obama’s own memoir, the subject of race is all the more unavoidable—and welcome. Remnick’s and Coates’s comments were unfailingly astute—but I did want to push back on one point that surprised me a bit.

Everyone has a theory about how Obama’s blackness helped him or hurt him. Obviously, Obama was able to maximize the ways it could help him and minimize the ways it could hurt him, the same way that Hillary Clinton would have tried to exploit/downplay her gender, or any other candidate would try to extract the positive aspects of any other notable trait he or she possesses.

But it remains a thorny subject. Our first “black president” is half-white, just as white as he is black, one might even say. Yet he signifies as black, culturally speaking, for reasons that stretch back to the abhorrent “one-drop rule” of slavery. Biracial Derek Jeter might not signify as “all black,” but in the more charged arena of politics, Obama usually does.

Add to this a subject that Remnick and Coates treated with some delicacy, that Obama’s father was not culturally African-American but simply African, which means that Obama had no obvious recourse to the cultural traditions and territory of regular African-American males, the ones descended from slaves. Obama is not a descendant of American slaves, and Remnick and Coates quite properly presented that as a problem for a candidate (Obama) trying to win the votes of African-Americans. You could almost say it could have been a problem along these lines: whites would disinclined to vote for him, since he signifies as “black”—but some black voters might also be (relatively) disinclined to vote for him—because he signifies to them as insufficiently “black.” Certainly that would have been a pickle.

Remnick and Coates were making the point that Michelle Obama sliced through this particular Gordian knot rather tidily. Michelle Obama, née Robinson, namesake of America’s most historic African-American baseball player.

So far, so good. Where Remnick and Coates lose me is their assertion that a hypothetical Obama with a white wife would have faced unusual—possibly fatal—problems. I should stress that I’m not shocked by that statement, and I’m not calling them on it for reasons having to do with political correctness. I’m just not sure the statement is as self-evidently true as the two men seemed to think.

Remnick’s statement was that Obama would not have secured 94% of the black vote if Obama’s wife had been white. Coates’s version, allowing for the usual ambiguity that occurs when people speak extemporaneously, seemed to bleed into the premise that Obama would not have won the election at all. Remnick’s statement is probably true in the narrow sense, if one adds the caveat that he could have secured 93% of the black vote and the statement would still remain true. As for Obama’s general prospects, it’s … a difficult statement to parse.

In some degree, this hypothetical seems to elevate cultural concerns over political ones. The fidelity of black voters to the Democratic Party is a political fact strong enough to trump a lot of other factors. It’s worth pointing out that in 2004, a white native of Massachusetts married to a white ketchup heiress (born in Africa, oddly enough) secured 88% of the black vote—and that was a low figure, in historical terms. And of course, Kerry lost the election. But are we saying that Obama would have done worse than Kerry? Are we saying that Obama’s political career would have stalled in Chicago because he would not have been able to appeal to “more authentically African-American voters” the same way? The counterfactuals are too involved to figure out, and—my real point—they ignore the salient role that the characteristics of specific human beings play.

Racially, Obama is whatever he is. In addition, he’s thoughtful, careful, eloquent, whip-smart, not prone to verbal gaffes … this is the man we are saying who could never have overcome his choice decades earlier to wed a white woman? I see the dynamic involved clearly enough … I just don’t think we can rule any outcome out so easily.

Predictions and hypothetical questions are bedeviled by recourse to average, typical exemplars. As an example, if you had asked a sportswriter, on May 30, 1982, whether any current major leaguer had a chance to break Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games streak, that sportswriter would very likely have said, “No. That is not possible.”

But of course Cal Ripken played the first game of his (quite a bit longer) streak that very day. Obviously the mental processes of that sportswriter would not have been up to imagining the possibility of a glorious outlier like Ripken—even though by definition that record would necessarily be broken by an outlier. Thinking about the ordinary major leaguers are of no use in answering a question like that.

Similarly, if we imagine this white woman that would supposedly have hindered Obama’s chances of becoming president, who is this woman, exactly? Or, more precisely, who might this woman be, exactly? Hillary Clinton? Cindy McCain? Teresa Heinz? Nancy Reagan? Nancy Pelosi? Barbara Ehrenreich? Sandra Bullock? Lorrie Moore? Even that short list of remarkable women shows the potential range involved.

Maybe I’m naive. Obama’s task was formidable enough as it was, and (as Remnick pointed out) his eventual path was in part the result of astonishing good fortune. Maybe it is true that Obama would never have gotten elected within Illinois, much less across the whole country, if he had not had an easy way to make regular black voters relate to him. But I tend to think of the issue in the following way.

Barack Obama married a remarkable woman. It’s safe to assume that if his chosen bride had been white, she would have been a pretty remarkable woman too. Her race might have complicated Obama’s political life. But alongside that, there are two other things one might venture as well: Obama excels at overcoming circumstances that would hold other people back, and this woman would have brought something to the project (I almost wrote “ticket”) in her own right.