Emily Gordon writes:

There are no words to describe the sadness we feel at the death of David, the man behind (among many other projects and passions) Blog About Town, who was a friend of The New Yorker, particularly its cartoons and cartoonists; an unwavering friend of Emdashes who always encouraged us to do our odd but heartfelt job more creatively and uncompromisingly; and a friend of mine. I could never match his generosity or his ingenuity in getting fellow New Yorkers to ditch their work-crazed ruts and get together, out to dinner, out to a play. His list of loyalists was the loyalest.

The last time we emailed, he invited me to see Twelfth Night. I couldn’t go. Here’s a short post he wrote about the play and its famous riddle about the initials M.O.A.I. In the comments (he was an active and conscientious commenter, including on his own posts), he wrote:

Methinks that M. O. A. I. could very well be a red herring, meant to torture Malvolio with its unsolvability. However: Now that I’ve (just) read about it containing the outer letters of Malvolio’s name, I also realize that continuing the progression would produce L. L. O. V., which is something close to love. That’s also plausible to me.

It’s a shocking loss, not least because it was so unexpected. He’ll keep his place of honor in the Emdashes Rossosphere for all time. Maybe someone else will take up the project of faithfully chronicling the New Yorker‘s Cartoon Caption Contest, mapping the winners, and tracking Daniel Radosh’s always hysterically anarchic Anti-Caption Contest. But no one will do it with so much L.L.O.V.

Later: Here’s a nice post about David from Radosh.net.

And later: Yesterday’s memorial service was one of the most touching occasions I’ve ever witnessed. I’ve been to three funerals in recent months for people far too young to die: Andrew Johnston, Michal Kunz, and David. It’s disquieting to hear eulogies by and for one’s peers (of course, one must also get used to this). But there’s an energetic, offbeat quality to such tributes that I can only describe as youthful, and that can be cathartic and apropos, too.

The first person to speak was the photographer Matt Mendelsohn, who knew David for almost all of their 46 years, and, with Matt’s permission, I wanted to share this part of his tribute with you. The caption contest line, you’ll be glad to know, got an enormous laugh. Everyone knew how passionate David was about the contest, but I didn’t realized he’d entered it so many times. And I didn’t know till yesterday that the huge group of passions and communities David either formed or enthusiastically promoted was just the tip of the iceberg. You wouldn’t believe how many people he was connected to, and how many people he connected. As another friend observed, “He was a giver.”

David was the smartest, brainiest, most loyal, most culturally aware friend I’ve ever had. He was interested in everything and he was interesting about everything. That is to say, there was no topic off bounds or out-of-reach for David. No subject, highbrow or lowbrow, he was unable to add a cogent, witty, insightful comment on. As a child, that could have been a topic of mild importance, say, the assumption to the presidency of Gerald Ford in 1974; of moderate importance, like the jazz trombone stylings of his idol, Bill Watrous; or, one of dire, absolute importance, like the groundbreaking 1968 Patrick McGoohan television series The Prisoner.

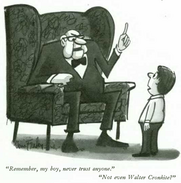

As an adult, that could mean a topic of mild importance, like the election of Barack Obama; of moderate importance, like discussing his one hundred and seventy-nine consecutive non-winning entries in the New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest; or, finally, a topic of dire, absolute importance, like the groundbreaking 1968 Patrick McGoohan television series The Prisoner.

David, young or old, was a collector of culture, a guardian of civility. You never so much as argued with David as debated him cordially. It’s no surprise that in the 1980’s, when Life magazine still published monthly, David was the Letters to the Editor editor. In an age now, when anonymous and vicious comments on the internet are run amok, the notion of David vetting every published letter for accuracy and intelligence seems downright quaint. But that’s just what he excelled at. He was a lifeline to a more literate and worldly world. The last postings on Blog About Town, the New York diary he kept up for years, include, quite randomly, tips for securing Shakespeare in the Park tickets, a word-for-word handicapping of the National Spelling Bee (“Kavya Shavashankar gets a huge Monty Python word, “Blancmange,” and swallows it whole; Kyle Mou gets lucky, I think, by drawing avoirdupois–and he takes full advantage of the situation”), and, finally, an old clip of the French songwriter Charles Trenet singing his 1946 classic “La Mer,” in his native tongue, long before Bobby Darrin re-wrote it into a hit song in 1959. Not knowing anything about Charles Trenet, I watched the clip, read the translation and thought to myself, “Wow, the original is so much more poetic.”

Will I someday use this morsel of knowledge David just gave me? I’m not sure. Like all of his wisdom, I’ve filed it in my brain, and someday it will find its way back out and into a conversation. These are the little gifts David loved to give.

-thumb-182x136.jpg)