Jonathan Taylor writes:

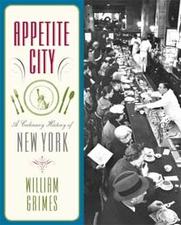

New York is food crazy right now, even more than usual. It’s also experiencing a renaissance of interest in local history, as new populations sweep into neigborhoods across the boroughs, and some, at least, take an interest in the surroundings they are the latest to reshape. So it’s hardly a surprise to see the publication this month of William Grimes’s history of New York restaurants, Appetite City (North Point, $30). What may be perplexing is that so little of this history was already widely known. The book helps us understand why it wasn’t. [Grimes will be discussing Appetite City with Ruth Reichl and others at the New York Public Library on Thursday Nov. 5, at 7:00 p.m. Info and tickets here.]

New York is sufficiently impressed with its own importance, but it has long been too busy occupied with what is happening now, and what’s the next big thing, to pay attention to the history that makes it important. Cities whose glory days are over do that. I’ve lived in New York for 15 years, and I know off the top of my head that the oldest existing restaurants in Boston are Union Oyster House, Durgin-Park and Locke-Ober; and that the oldest in New Orleans is Antoine’s.

But what is the oldest restaurant in New York? I had hardly given it a thought. It turns out it’s not that clear, and whatever the answer is, it’s of limited interest, and cannot illuminate New York’s past in the way that these others do for their cities. The history of New York’s restaurants, as in other fields, is one of constant change, creative destruction, and nimble assimilation of other places’ traditions and talents. The only thing capable of embodying the essence of New York’s history is its present—the notable absence of so much of its history is a result of the way that history unfolded.

Grimes’s opening chapter describes a New York difficult to imagine: “A City Without a Restaurant.” The early history of eating out in New York is the history of the notion of eating outside the home at all. For the Dutch-descended Knickerbocker society of the early 19th century, dining was done in private, and in any case, they regarded the food generally served in public—at chophouses—as “foreign,” because it was English. Those chophouses, and lesser coffeehouses and pie counters, served what Grimes says was the American city where it first became customary not to return home to consume lunch.

In the busy city, eating out was thus first a matter of necessity. But the idea of going out to eat as a pleasurable activity in itself was a slightly later import. Abram Dayton, in his 1897 memoir Last Days of Knickerbocker Life in New York, recalled the “foreign element” that distinguished Delmonico’s, opened in 1827 by Swiss brothers as a French café. Delmonico’s introduced the phenomenon that defines one aspect of New York as a restaurant city: aspirational dining. Fed by its own farm in the village of Williamsburgh on Long Island (now Brooklyn’s Williamsburg), it offered above all the latest in Parisian trends, but also skimmed the world’s cuisines, offering, according to New York bon vivant Sam Ward, everything from “the caviare of Archangel, to the ‘polenta’ of Naples, the ‘allia podrida’ of Madrid, the Bouillabaise of Marseilles, the ‘Casuela’ of Santiago Chili, and the Buffalo hump of Fort Laramie [sic throughout].”

Over the course of the 19th century, Delmonico’s became New York’s most renowned restaurant, or rather restaurants: Its expansion illustrates another reason New York’s dining history isn’t well preserved—it kept moving. Their second location at 76 Broad St., opened in 1834, became the main restaurant after a fire destroyed the original 23 William St. site the next year. Lorenzo Delmonico, keeping his eye on the city’s growth uptown, moved the “flagship” Delmonico’s to a series of locations opened successively at William and Beaver in 1837; Chambers and Broadway in 1856; Fifth Ave. and 14th St. in 1862, relocated in 1876 to Fifth Ave. and 26th St. by Madison Square; and finally to Fifth and 44th, the last location, which closed in 1923.

In Grimes’s chapters focusing on Madison Square, we see New York’s emerging economic preeminence in the second half of the 1800s, as manifested in the city’s first fully realized nocturnal entertainment and social mecca. Lavish hotels, like Hoffman House and the Brunswick, boasted restaurants matching the Delmonico’s standard (and poaching its cooks), and racily decorated bars that poured the first wave of Martinis and Manhattans. The Madison Square scene functioned both as stage for the high-society likes of Edith Wharton, who gathered at the Café Martin (opened in the Delmonico’s space when that moved to Midtown), and auditorium for a mass audience of gawkers: the area was the pre-Times Square theater district, the site of a Barnum Hippodrome and, of course, the original Madison Square Garden.

While the upper crust migrated determinedly from downtown (Bleecker St. was “the Park Avenue of its day” before 1850) to Union Square to Madison Square to Midtown, Appetite City gives glimpses of the surprising pasts of the neighborhoods in its shadows. Park Row, the 19th-century home of New York’s newspaper industry, was lined with cheap spots that served journalists around the clock, like so-called “beef and” restaurants. (Journalists, in return, fancifully embellished on the kitchen argot that waiters supposedly used to shout orders to the kitchen. The symbiotic relationship between the news media and restaurants is a constant theme in the book.)

And who knew that what we now call SoHo was once settled by French emigres who patronized grubby cuisine grand-mere eating houses along Wooster Street? Nearby, the stretch of Houston just east of Broadway was once a notorious den of gambling and theivery, concentrated around the oyster saloon Florence’s and the concert hall Harry Hill’s. (It’s just barely possible to feel that the block’s raucous late-night history survives a bit in old-time dive bar Milano’s and Botanica, a.k.a. the former Knitting Factory.)

Throughout New York’s relatively short history, composed mostly of the arrival of waves of newcomers, what’s “authentically” New York has always been fiercely, and pointlessly, contested. At the turn of the 20th century, vast “lobster-palaces”—Rector’s at 44th and Broadway, Churchill’s at 49th, Jack’s at 42nd and Sixth—fed thousands of pleasure-seekers in a district that redefined the image of New York high life, Times Square, and prompted a now-familiar kind of discourse about what defined a “real New Yorker”:

There was disagreement about who belonged to lobster-palace society. The more jaded journalists dismissed the whole tribe as nothing more than out-of-towners desperate to spend money and woop it up. Convinced that they were seated amidst real New Yorkers and the cream of the theatrical crop, the rubes stared agog at their fellow visitors from Rapid City and Kalamazoo, and endured the close company of big-spending loudmouths….

What could be more “authentically” New York than the visitors’ quest to show up and be in the middle of it, and the entrepreneur’s readiness to furnish a ready-made spectacle. In any case, the original lobster palace, Rector’s, was an import: Chicago restaurateur Charles Rector simply transplanted the restaurant model that had already earned him his fortune in the Loop.

And while today, as the plans for a T.G.I. Friday’s in Union Square understandably prompt bemoaning of the dilution of the city’s character by national chains, it’s worth noting that at the turn of the 20th century, restaurant chains were the rage in New York. The city was the birthplace of the Childs restaurants, which from 1889 to 1928 grew to 112 restaurants in 33 cities in North America (including one in Union Square). At each stage of the city’s rapid development, an ever-shifting, self-centered sense of “history” is repeatedly generated. In 1921, Collier’s magazine lamented that Broadway around Times Square, “once famous for ‘gilded’ restaurants,” was now lined with “dairy restaurants, pastry shops, rotisseries, cafeterias, and ‘automats'”—the last of which are now themselves objects of nostalgia of “old New York.”

Today, New York is taken with a food culture hungry for the brand of authenticity preached by Michael Pollan and Alice Waters. But this city, although a gastronomic capital, is not the custodian of a traditional local cuisine or a terroir. To a degree, it resembles Paris in this way, since Paris is famous not because of the cuisine of the ÃŽle de France, but as magnet and stage for the entire country’s products and cuisines. But in Paris, the fanciful use of those products at high-end restaurants became itself a fully developed culinary tradition. In contrast, Grimes notes, “New York’s hallmark as a dining city is not the excellence of its best restaurants, it’s the uncommon diversity of ‘national cooking styles’ in one place.” And, like the entertainment industry they’re so connected to, the “best” restaurants also depend on talent and trends from the sticks gravitating to the New York City stage, be it Chicago’s Charlie Rector or Waters’s Californian farm-to-table movement.

The one kind of eatery that historically is as authentically local to New York as a bouchon is to Lyon is the oyster saloon—and that’s one that, typically enough, is extinct, due to overharvesting of the once seemingly limitless oyster supplies of regional waters. Mark Kurlansky, of course, explained the pervasiveness of this shellfish in New York’s economic, cultural and natural life in his book The Big Oyster. But Grimes shows vividly how oysters were, in the 19th century, the city’s “great leveler.” They were an omnipresent cheap snack food, whether a half-dozen (seven) for a dime, a hot chunk of oyster pie, or pickled oysters. (Grimes rightly finds the disappearance of the latter puzzling—with luck, maybe they’ll be revived by an artisanal fishmonger analogue of the Marlow & Daughters-style butcher shop.) At the same time, some oyster saloons functioned as the era’s “power restaurants,” whether the sumptuous Downing’s on Pell St., or the ostentatiously severe Dorlon’s at Fulton Market. The Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal was founded before the final end of the oyster era and is, in Grimes’s estimation, a good “approximation” of this old-time New York institution.

But cheap oysters as the quintessential food of the city’s daily life are a thing of the past, just as it’s difficult to imagine Broadway between Madison Square Park and 34th St. as “ablaze with the electric light” illuminating thronging crowds of night-owls. Yet even as so much of New York’s restaurant past has vanished, much of it is simply reincarnated, since many of the city’s eating requirements stay the same. Once you’ve read Appetite City, almost any kind of restaurant reveals itself as merely the latest avatar of a New York archetype.

“My theory about a restaurant is that to be the right sort of an eating place it must be closely related to its source of supplies,” wrote the man behind a meticulously conceptualized restaurant that was supplied by its own farm outside the city; “We feel that certain ideals of cooking and furnishings should be expressed in connection with a restaurant.” The restaurateur in question is not Dan Barber, but Arts and Crafts furniture designer Gustav Stickley, whose Craftsman Restaurant on East 39th St. lasted tantalizingly briefly, from 1913 to 1914. Graydon Carter’s Waverly Inn has as predecessor in the Pfaff’s of the 1850s, at Broadway and Bleecker, where Saturday Press magazine editor Henry Clapp “cracked the whip” over a hand-picked circus of “self-proclaimed geniuses—most of them future footnote material.” A craze for tamale carts made a notable appearance a century before the Red Hook soccer fields—”chicken” tamales sold by Irish vendors and actually made with veal, then a cheaper meat than chicken!

And the pizza slice can be said to play the same role for the city that the oyster once did: the cheapest meal available on every street, but an object of appreciation up and down the social scale. Apart from a mention of the origins of pizza’s presence in New York, though, there is scant mention in Appetite City of this ubiquitous food, and food culture, of the city. It’s almost impossible to make a fair criticism of what has to be left out, after everything that Grimes has managed to put into this book. But here’s my only real quibble. Until the early 20th century, Grimes vividly conjures the scope of popular food practices alongside the heights scaled by the likes of Delmonico’s. But the in latter part of the book focuses more narrowly on fine dining trends—telling that story as a former Times restaurant critic can—but also at the expense of the true vernacular dining of the city’s millions.

This makes the more recent history weaker for at least two reasons. It neglects to carry historical threads the book has traced for so long all the way to their fascinating manifestations in the present day. I was disappointed, after the extensive genealogy of greasy spoons—the “coffee and cake” restaurants, “beef and…” joints and “hash houses”—not to see exactly how these led to what today’s New Yorkers know as diners.

Secondly, it loses sight of Grimes’s own maxim that it’s the “diversity of national cooking styles,” not only the “best” restaurants, that define this “restaurant city.” And thus it can’t account for what is already shaping up as the next chapter in New York’s culinary history: the fact that the city’s foodies are now as fixated on seeking out the best taco cart or Hunan hot noodle hideaway as on getting the impossible Momofuku reservation—if not more.

But that’s just to say of Grimes’s achievement, “More like this, please.” As the current quest for authenticity mandates attention to (sometimes imaginary) tradition and heritage, and restaurants continue to both cause and symptom of the changing geography of the city—functioning as chicken and egg in the familiar cycle of neighborhood gentrification—Appetite City is required reading for understanding more than just how we eat in this city.

P.S.: Appetite City has some New Yorker angles too, with a number of its articles serving as key sources, including:

“Romance, Incorporated,” a February 4, 1928, profile by Margaret Leech of Alice Foote MacDougall, “the Martha Stewart of the 1920s” in Grimes’s words, and creator of cozily middlebrow chain of restaurants intended for working women to repair to.

Margaret Case Harriman’s two-part profile of the headwaiters of Upper East Side society restaurant The Colony, from June 1 and June 8, 1935.

“The Ambassador in the Sanctuary,” Joseph Wechsberg’s 1953 profile of Le Pavillon proprietor Henri Soulé.

Geoffrey Hellman’s 1964 profile of Joseph Baum’s Restaurant Associates, “Directed to the Product.” (As told by Grimes, the tale of Restaurant Associates’ impeccably researched artificiality is a key chapter in the history of the kind of “fine-dining business” now exemplified by the McNally, Danny Meyer and other restaurant “groups.”)

Grimes also notes two early New Yorker writers who authored guides to the city’s restaurants: George S. Chappell (The Restaurants of New York, 1925) and Walter R. Brooks (New York: An Intimate Guide, 1931).