_Martin Schneider writes:_

You know it’s a good day when James Surowiecki announces he’s starting a “blog”:http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/jamessurowiecki/ version of his consistently insightful “Financial Page” column. Only a little more than a day and already there are five meaty posts up there. He wittily “notes”:http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/jamessurowiecki/2008/10/welcome-to-the.html that the debut of that column precipitated a reversal in the market in 2000, so we hope for more of that.

Monthly Archives: October 2008

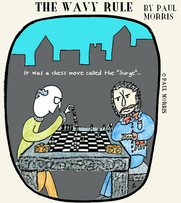

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Is There an Eco in Here?

Fun Charity Event in Washington Heights with Junot DÃaz

_Martin Schneider writes:_

Junot Díaz’s novel only won the most recent Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, and I haven’t heard anyone say a bad word about it. I just got my copy of _The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,_ and I can’t wait to read it! Do attend, it looks like a good time and it’s for a good cause! Press release follows:

Junot Díaz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Dominican-American author of

_The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,_ is coming to Washington Heights!

Junot will be joining CoSMO, Columbia’s free student-run primary care

clinic, for a book reading and conversation on Friday, November 7th at

7:30pm. All proceeds go toward prescription medications for CoSMO’s

uninsured patients (“www.cosmoprimarycare.org”:www.cosmoprimarycare.org).

The night will also include free appetizers provided by Mamajuana

restaurant, old school hip-hop sounds by DJ Strike (former tour DJ of

De La Soul), and visual arts by the Sound of Art collective

(“www.soundofart.net”:www.soundofart.net)

Don’t miss this incredible night of literature and conversation

celebrating the communities of Quisqueya Heights!!!!

Junot Díaz: A Reading, a Conversation

Friday, November 7th at 7:30pm

Alumni Auditorium

William Black Research Building

650 W. 168th Street

New York, NY 10032

Tickets sold “online”:https://www.ovationtix.com/trs/pe/769922:

$15 general, $10 with student ID

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Raggedy Andy

_I like how Andy Rooney looks like a jack-o-lantern! Hee. Click to enlarge!_

More by Paul Morris: “The Wavy Rule” archive; “Arnjuice,” a wistful, funny webcomic; a smorgasbord at Flickr; and beautifully off-kilter cartoon collections for sale (and free download) at Lulu.

Vile Bodies: David Levine’s Prickly New Yorker Past

Jonathan Taylor, whom we’ve just welcomed to the Emdashes team, writes:

This article in the November Vanity Fair explains the disappearance from The New York Review of Books of the artist who helped define its virtually unchanging look: David Levine, who caricatures the glorious and the notorious of belles lettres and statecraft with huge heads on vestigial bodies (or, sometimes, vice versa). His vision succumbing to macular degeneration, Levine in 2006 for the first time had work rejected by the Review for reasons of execution rather than scurrilousness. The article is a fine sidelong portrait of a publication that’s venerable, yet in fact still young enough to be only now exiting (slowly) the era of its founders.

It also turns out that Levine had several taste tiffs with The New Yorker, for which he has provided 71 illustrations. One reject was this watercolor of Bush in flightsuit atop an array of coffins, which ran in 2005 instead in the Review. It seems practically banal today, but plausibly exceeds the limits of The New Yorker‘s political prudence. (The magazine’s emphatic Barack Obama endorsement is still careful to specify that “There is still disagreement about the wisdom of overthrowing Saddam Hussein and his horrific regime.”)

A little more alarming is the tale of a cartoon of Mahmoud Abbas and Ariel Sharon that the magazine altered unilaterally. It removed some missiles that accompanied Sharon as a counterpart to the machine-gun wielding masked militants looming behind Abbas. David Remnick told Vanity Fair, “David Levine is a great political artist and kept on publishing with us after this, but all I remember about this was thinking that with Sharon being so ominously huge in the drawing, the bombs were too much.” It certainly seems that Levine has a thing about Sharon’s hugeness, if not his enormity (the kaffiyeh on this Sharon I think perfectly typifies Levine’s blunt sharpness, if you will).

Perhaps the context is useful in reading Levine’s rather sweeping take on the state of New Yorker cartooning in an interview with The Nation: “I think they’ve let down the barrier of quality, and it is just terrible.” (Can this be true of every current contributor, including the older cartoonists who continue to draw regularly for the magazine?) But the anger seems rooted in his determination that cartooning have a legible positive purpose: “Caricature is a form of hopeful statement: I’m drawing this critical look at what you’re doing, and I hope that you will learn something from what I’m doing.” Levine compares the cartoonist to the golem created by a rabbi to fend off anti-Semitic attacks: “When things are settled, he’s not needed.”

The New York Review‘s site hosts a complete Levine gallery, searchable by subject name or categories like “Tycoons, Plutocrats, Midases.” The overlap of the two magazines’ preoccupations means there are a lot of images of New Yorker interest over there: David Remnick; William Shawn; a passel of Updikes, from 1971 to 1994; a quorum of Malcolms, including a Gladwell and two contrasting Janets; a Joan Didion or two; a couple of somewhat disturbing Rebecca Wests; even a rather calming Helen Vendler.

New Yorker Festival: Oliver Stone’s Got Guts

“I’m a dramatist, not a journalist.” This is currently Oliver Stone’s favorite mantra, repeated at the Director’s Guild Theater with David Denby and, for instance, on Bill Maher’s HBO show last week. I take it as a sign that his aims have become more modest than in his _JFK_ days, if not an outright shield against the legions of fact-checking critics who, in _W.,_ will doubtless find much fault with Stone’s unique use of composites and rearranged chronology to drive home this or that emotional or political point.

“Nixon’s the grandfather of Bush, in a sense. Reagan’s the father,” said Stone. (I await the Reagan biopic that would complete the trilogy. Actually, that idea’s not half bad.) On the poor box office performance of Nixon, Stone said, “He evokes guilt and paranoia, and those qualities are not much in demand.”

Apparently refusing to absorb that maxim, Stone has produced a movie more than a decade later about George W. Bush. Three lengthy clips were shown, dating from 1978, 1988, and 2002. The first takes place at the barbecue party at which the erstwhile Laura Welch (embodied by Elizabeth Banks) and W. meet. Bush swigs throughout from a beer bottle and appears somewhat cowed by Laura’s identity as a librarian. It’s worth pointing out that Josh Brolin is pretty awesome as W. In the Crawford section his callowness doesn’t quite convince, but as W. ages, Brolin really finds his way to the heart of the character. We’ve all lived with the president for the last eight years, and Brolin’s impersonation won’t distance anyone in the slightest, I think.

The 1988 scene takes place in his father’s vice presidential office, Rove and W., clearly not among the veep’s core advisors, engage in a bit of crosstalk about the rise of the religious right (Poppy is not down with the program). After everyone else is ushered out, W. shows his father the as-yet-unaired Willie Horton ad, and then comes the sort of anachronistic dialogue for which the movie will surely become renowned. W. observes that what with this ad and “that picture of Dukakis in a tank,” Bush’s election is assured, an observation scarcely imaginable without heaps of hindsight, of course.

The 2002 scene demonstrates all of the weaknesses and strengths of Stone’s project. The setting is the Situation Room, and all of the familiar players (Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, Powell, Wolfowitz, Rove, Bush) discuss what to do about Iraq. (In person, Stone persistently calls the former secretary of defense “Rumsfield.”) In the scene, several different characters deliver extended speeches explaining this or that point of view. The showdown between Powell (Jeffrey Wright) and Cheney (a marvelously restrained Richard Dreyfuss) is the scene’s climax. As before, statements known to be made in other places and at other times are heard to be uttered here, including the terms slam dunk and misunderestimated.

To Denby, Stone defended these quirks by pointing out the utter opacity of the Bush administration’s decision-making process until quite recently; only in the last two or three years have journalists produced books shedding light on these meetings. (Of course, herein lies the case for waiting until a president is out of office for such attempts at retrospective assessment.)

For all of his excesses, at heart Stone remains almost touching in his idealism. If one asks, “does Stone engage in character studies or works fomenting political change?” The answer I think must be that Stone believes the former to lead to the latter. That is, there is a faith at work here that if audience members can only grasp the “real” person in question (mediated in whatever fashion, using whatever dramatic shortcuts are necessary), then political change will result. And the ascent of Obama is at least a partial proof that the true nature of the Bush administration _has_ penetrated the public at large.

Subtlety was never Stone’s strong suit; he’s the type who underlines words three times. Yet from all appearances this movie is not the hatchet job one might expect. And he’s not exactly fashionable right now, if that’s even the right term for Stone’s status during his peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s. His ability to impose his will on the national discourse is not what it once was. But despite it all, he puts himself on the line as much as in 1988; he has recently produced a documentary about Castro and has another project, since stalled, about My Lai, and mentioned Hugo Chavez and Ahmedinejad as potential future subjects. Somehow you’ve got to admire the old SOB.

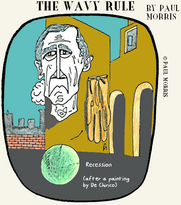

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Modernist Depression

_In addition to Chirico, this one reminds me of the covers of those old “Choose Your Own Adventure” “books”:http://www.somethingawful.com/d/comedy-goldmine/choose-your-own.php?page=2 (warning, the ones in the link are fake). Click to enlarge!_

More by Paul Morris: “The Wavy Rule” archive; “Arnjuice,” a wistful, funny webcomic; a smorgasbord at Flickr; and beautifully off-kilter cartoon collections for sale (and free download) at Lulu.

Literary Notes from All Over

Benjamin Chambers writes:

Boy, the literary news has just been piling up. Here’s a quick taste:

* The Nobel prizes were just handed out, and American poets got skunked—as usual, according to David Orr in the Times. According to Orr, New Yorker poets John Ashbery and Adrienne Rich both shoulda been contendas. (Larissa MacFarquhar did a profile on Ashbery in the November 7, 2005 issue, but no one seems to have done the same for Rich, although D.T. Max did a Talk piece on her refusal of the National Medal of the Arts in 1997.)

* Philip Roth was recently interviewed on NPR about his new novel. I’m not a fan of Roth’s work, but I found Robert McCrum’s long interview with him in The Guardian fairly interesting, particularly the section that talks about the hostile reception his story, “Defender of the Faith,” which appeared in the March 14, 1959 issue of TNY: “For much of the Sixties he was declared a traitor to his people, abused and denounced up and down as worse than anti-Semitic.”

* This week, Yale celebrates the 250th birthday of Noah Webster, author of the eponymous dictionary. Webster, I learned, is the person responsible for separating American English from British English in key ways: “The French version of words like ‘centre’ [also used by the Brits] became ‘center’ and he dropped the British ‘u’ in words like colour’ and the redundant ‘k’ in musick and other words.” Jill Lepore, who wrote a November 6, 2006 essay on Webster for TNY, is a fan: “You cannot look up a dictionary definition today and not stumble across many definitions that were written by Noah Webster.” Happy birthday, Noah.

* In this Kansas City Star profile of novelist and poet Jim Harrison, I found a reference to his September 6, 2004 TNY piece, “A Really Big Lunch.” Concerns a 37-course meal he once had, which took 11 hours to eat. Gotta look that one up … feeling a bit peckish.

* May not be as good for sales as the Oprah Book Club, but Melville’s Moby-Dick may soon become the Massachusetts state (er—commonwealth) novel, if its state House of Representatives has anything to say about it, and apparently it does. The bill proposing the honor for Moby-Dick was filed “at the request of fifth-grade pupils at Egremont Elementary School so they could follow the bill through the legislative process.” However, “those pupils are now in the seventh grade, and the bill still isn’t law. It needs to pass the state Senate and get the signature of Governor Deval Patrick.” While you’re waiting for it to become official, check out John Updike’s May 10, 1982 TNY review of Melville’s career after Moby-Dick came out. Updike reverses quite a few myths about Melville, chiefly that Moby-Dick was not, as is popularly supposed, a financial or critical flop.

* Not sure this qualifies as “news,” but I’d never seen these writing commandments from Henry Miller before. Not sure if they’re really his or not, but they might be worth checking out.

Have fun surfing!

Are You Funny? Tag-Team Caption Contest Throws Down the Wit Gauntlet

_Longtime friend of Emdashes “Ben Bass”:http://benbassandbeyond.blogspot.com/ contributed a terrific “report”:http://emdashes.com/2007/10/avenue-queue-a-new-yorker-fest.php from last year’s Festival about waiting on line for tickets; clearly Ben has a talent for making the best of a situation. This year he weighs in on the Cartoon Caption Contest event, held on the Festival’s opening night._

The 2008 New Yorker Festival kicked off Friday evening with a serious town hall meeting on race and class in America at which Thomas Frank, Cornel West, and David Remnick parsed those weighty issues. For those of us in the mood for something lighter, there was the Cartoon Caption Game, a friendly competition hosted by cartoon editor and bon vivant Bob Mankoff.

We entered to find a large open room dotted with nineteen round cocktail tables. At each table, presiding over four empty seats, sat a past New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest winner or finalist, easily identifiable by a red baseball cap emblazoned with the New Yorker logo and “Team Captain.” Our captain was a friendly New York City psychiatrist named Richard. Displaying the discretion so crucial to his profession, he declined to share his last name upon learning that I would be writing about this evening. He did, however, recite his winning caption, in which a man seated at an office desk in an electric chair says into his telephone, “Cancel my twelve-oh-one.”

If “What’s your line?” was the icebreaker that launched a million midcentury conversations, on this night the de rigueur greeting was “What was your line?” In a room full of strangers, the one fact you knew about these smiling folks was that each had written a good joke and so had a tale to tell. That was all we needed to get things rolling. On the other hand, as attendees (sorry, “contestants”) drifted into the room looking for seats, the captains’ icebreaker was, “Are you funny?” My companion and I answered with a deflective optimism; a bright young couple filled the last two seats with an appealing “We’re kind of funny.”

Of course, most people who attend something called the Cartoon Caption Game think they’re funny, and many of them are right. The trouble is, at least where competitive cartoon captioning is concerned, delight at one’s own witticisms often accompanies a certain solipsism, an unwillingness to acknowledge that others might have thought of the same joke, or even improved upon it. Bob Mankoff calls this malady “idea rapture.”

Mankoff’s introductory remarks included an illustration of this particular type of narcissism. He displayed a recent Caption Contest cartoon of a courtroom scene in which a killer whale is seated at the defense table. Like everyone else in the room, my first reaction was to posit that the whale’s putative killer status was at issue. In fact, I couldn’t think of any other joke. Sure enough, the winning caption was “Objection, Your Honor! Alleged killer whale.”

Mankoff then read an angry letter he received from a contest entrant who had submitted the same joke. The letter writer, convinced that he alone had come up with this line, wrote that he’d scribbled it on a magazine he’d left on an airline flight and bitterly accused the contest winner of finding the magazine and submitting the line as his own work. Mankoff’s elegant response was to send the writer the other fifty or so nearly identical submissions of the same joke.

His amusing spiel (“A lot of you are winners of the contest. The others are losers”) also described the process of administering the caption contest. The New Yorker receives between five and seven thousand contest submissions per week, with over a million to date and counting. As the readership has embraced the contest, it has taken on a momentum of its own, even spawning a new book on the subject, conveniently on sale this very evening.

After Mankoff explained the format, the competition began in earnest. Various gag illustrations from New Yorker cartoonists were projected seriatim for five minutes each, during which time each table huddled and brainstormed its caption ideas. When the time elapsed, each table submitted its best line for consideration by the evening’s panel of judges, New Yorker cartoonists Mankoff, Jack Ziegler, Barbara Smaller, and Matt Diffee, who chose three finalists for each cartoon (sound familiar?).

As in the magazine, where online voting determines the winner, popular acclaim, in this case in the form of applause, awarded the points for first, second, and third place. The evening’s cumulative point leaders would take the first prize, prints of their best-captioned cartoon; the runner-up table would receive signed copies of the new Caption Contest book.

Our group, known for lack of a more creative name as Table 14, came out firing. The first illustration was of a five-story-tall rabbit chasing a throng of business-clad types down a city street, Godzilla-style. A fleeing man in a suit was doing the talking. Table 14’s submission: “I miss the bear market.” Good enough, as it turned out, for second place, but we were aced out by another solid one: “And yet it’s adorable.”

The second cartoon was a Matt Diffee drawing of a domestic scene in a cave that a caveman and cavewoman had improbably furnished with sleek, modern-looking furniture. The club-wielding husband was the speaker. We liked our “There’s a difference between gathering and shopping” but went with “Wait ’til you see the Cadillac I speared”; apparently we liked it more than the judges did.

As the evening wore on, the scarcity of really good jokes became apparent. Over and over, a line we had thought of but rejected as too obvious or hacky would pop up among the finalists as another table’s submission. Did this make us funnier than them, or just worse evaluators of which lines would go over big? We like to think that both are true.

Much like the actual NYer C.C.C., the exercise became a mind game in which we tried not just to think of funny lines but also to predict which of these would please the judges. As a recent Caption Contest winner wrote, “You are not trying to submit the funniest caption; you are trying to win The New Yorker‘s caption contest.”

In the event, the wiseacres at Table 7 ran away with the Cartoon Caption Game. I’m happy to report that they won it not with Table 14’s rejects but with a number of genuinely witty and surprising lines. I hope John McCain, a few weeks hence, will graciously echo our content resignation at having lost to a demonstrably superior opponent.

As for New Yorker Caption Contest idea rapture, not even your correspondent is immune. Last spring I submitted a line my friends and I thought was at least as good as the three somewhat humdrum finalists. After mine wasn’t chosen, I wrote about the small setback, but it was mere whistling in the wind; I still didn’t know whether my joke was considered and rejected, or not even read among the thousands of submissions.

Happily, I got a small measure of satisfaction from Farley Katz, the New Yorker cartoonist, former Mankoff assistant, and Caption Contest first line of defense to whom I’d emailed the above link hours earlier. He told me that he’d checked his records and found that a number of people had submitted the same joke I had and that he had declined to include it among that week’s thirty or so semifinalists. At least now I know I was in the game.