In honor of the week of David Remnick’s tenth anniversary at The New Yorker, here’s our tribute, in the form of a drawing by staff cartoonist Paul Morris, to the hardworking reporter and editor’s diverse contributions to the journalistic skyline. Click to enlarge!

Monthly Archives: July 2008

The New Yorker Guide to Today’s China

I was intrigued by Emily’s observation a couple of weeks back that The New Yorker has been covering China so assiduously in recent months.

That got my devious little mind into gear. I looked into it, and she sure isn’t making it up. There have been a bunch of articles covering China since the start of the year, and the good news is, most of them are available online.

With only about three weeks until the start of the Beijing Olympics, we provide a handy list. (I’ll update this periodically.)

Evan Osnos, “The Boxing Rebellion,” February 4, 2008

Peter Schjeldahl, “Gunpowder Plots,” February 25, 2008

Peter Hessler, “The Wonder Years,” March 31, 2008

Jonathan Franzen, “The Way of the Puffin,” April 21, 2008

Paul Goldberger, “Situation Terminal,” April 21, 2008

Evan Osnos, “Crazy English,” April 28, 2008

Yiyun Li, “A Man Like Him,” May 12, 2008

Peter Hessler, “After the Earthquake,” May 19, 2008

James Surowiecki, “The Free-Trade Paradox,” May 26, 2008

Paul Goldberger, “Out of the Blocks,” June 2, 2008

Pankaj Mishra, “Tiananmen’s Wake,” June 30, 2008

Paul Goldberger, “Forbidden Cities,” June 30, 2008

Alex Ross, “Symphony of Millions,” July 7, 2008

Patricia Marx, “Buy Shanghai!,” July 21, 2008

Evan Osnos, “Angry Youth,” July 28, 2008

David Remnick, “The Olympian,” August 4, 2008

Did I miss any? Be sure to let us know!

Speedboat: Jen Fain Is the Written Thing

I read Renata Adler’s 1976 novel Speedboat last week. I found it a fascinating testament to…

…and right about there is where my difficulties began.

I had originally wanted to write that the book, while brilliant, is not a novel, at least not a novel with recognizable characters embroiled in a plot that’s resolved in some fashion, but after reading a bit of the critical commentary about it, I realized that this reaction is unoriginal and not so interesting. So what is there to say?

It’s not that Speedboat is simply dated. It is dated, very dated, but the book is also good, an unmitigated pleasure to read. Lots of books are dated in much more ordinary ways that make them difficult to read or enjoy today. Speedboat isn’t like that.

Perhaps this is the notion I’m groping for: A book like Speedboat couldn’t be published today in this form, much less receive the rapturous critical reaction it seems to have received in 1976. To use a medical metaphor, Speedboat is a diagnosis of the ’60s that cannot escape also being a symptom of the ’60s.

I don’t mean to offend. It’s a nifty book; it’s rare that one can say one has read a novel in which there is a pleasure to be found on virtually every page. But the techniques involved are so out of fashion that I’m not sure an editor would let it pass his or her desk in its published form. A novel consisting of a series of penetrating and thinly connected observations in which no plot point can be said to occur? It sounds like a hard sell, today.

Maybe we’re the poorer for it. Maybe their fashions were better than our fashions. Maybe I’m a terrible conservative when it comes to plot.

OK, that’s the meat of my reaction. A few odds and ends about the paperback edition I was reading, pictured below, found at the $0.48 bin at the Strand.

On the back is a picture of Adler by Richard Avedon, and underneath it says, in big red letters (hilariously, in my view): “JEN FAIN IS THE REAL THING.” Then underneath, in regular type, there are the words, “She is beautiful, hip, brilliant. She had been everywhere, done everything, known everyone.” And so on from there. It’s not that any of that is inaccurate, exactly, but it does create expectations the book isn’t designed to meet.

At the end of the book are a few pages of advertisement for other writers carried by the Popular Library imprint. One page touts Anne Tyler (spelled correctly), followed by a blurb from People: “To read a novel by Ann [sic] Tyler is to fall in love.” (Who’s that?) On the next page, we learn that a writer named Dorothy Dunnett “could teach Scheherazade a thing or two about suspense, pace, and invention.” And the page after that it says that “no other modern writer is more gifted a storyteller than Helen Van Slyke.”

Why is dated hype is so much funnier than other kinds?

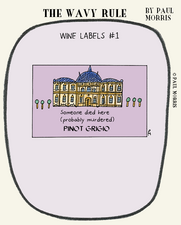

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Wine Not?

Paul turns his bottomless imagination to something that’s design-, typography-, and libation-related all in one: a mini-series on whimsical wine labels. Here’s the first! Click to enlarge.

More Paul Morris: “The Wavy Rule” archive; a very funny webcomic, “Arnjuice,” a motley Flickr page, and various beautifully off-kilter (and freely downloadable) cartoon collections at Lulu.

Some People, Places & Things That Will Not Appear in My Next Novel

What could be cooler than accidentally running across one of my favorite “John Cheever”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Cheever stories, “Some People, Places, and Things That Will Not Appear In My Novel”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/11/12/1960_11_12_054_TNY_CARDS_000265256, in the The Complete New Yorker?

Way cooler: realizing that this story, from the November 12, 1960, issue, is longer and more revealing than the cut-down version that appeared in Cheever’s 1961 collection Some People, Places & Things That will Not Appear in My Next Novel (note that added “next”), with a new title: “A Miscellany of Characters That Will Not Appear.” (The latter version is also in his famous collection The Stories of John Cheever.)

Yup, that’s right: he hacked it before anthologizing it.

Both versions are exactly what the title promises: a list of things Cheever (or his narrator) finds irritating, despicable, or disappointing in contemporary fiction. The revised version is seven items long; the original runs to 11, plus a coda. More of an essay than a story, its spleen still startles, even after nearly 50 years.

When he revised it, Cheever cut item 5, one of several cheap shots in the original. It reads, in its entirety, “The dumb blonde, because she’s no dumber than you, whoever you are.” He was right to think better of it (though I confess I like the audacity of its pointed finger), as well as item 7, his swipe at “J. D. Salinger”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._D._Salinger, whose success he envied:

Almost all autobiographical characters who describe themselves as being under the age of reason, coherence, and consent; i.e., I mean I’m this crazy, shook-up, sexy kid of thirteen with these phony parents, I mean my parents are so phony it makes me puke to think about them and that’s why I live in Mexico to keep away from these phony parents.

But I was sorry to see several other items go, short fictional sketches that displayed all of Cheever’s compassion and flair for the nomenclature of despair and regret. Item 4, for example, where he describes the jaundiced host of a suburban cocktail party, now keenly aware of his mortality:

He knew that time passed over the apple, over the rose, that time passed even over the old football in the coat closet, but he was astonished to find that time had passed over him. Why hadn’t someone told him? What had become of that form that used to cause so much consternation at the edge of the swimming pool?

It’s funny to think of this ordinary man musing on his own death with such graceful phrases, but it’s part of Cheever’s magic that he invests his characters so generously. Of the drunk advertising man in item 10, Cheever writes,

Here we see, as on a sandy point we see the working of two tides, how the powers of his exaltation and his misery, his lusts, and his aspirations have stamped a wilderness of wrinkles onto the dark and pouchy skin. He may have tired his eyes looking at Vega through a telescope or reading Keats by a dim light, but his gaze seems hangdog and impure.

Vega? Keats? Not a chance. For Cheever’s characters, though, these are real possibilities. Death and failure may never be far from their minds, but he is quick to grant them depth and protect them from judgment.

For example, when Charlie Pilstrom in item 6 converses with his neighbors while waiting on a train platform, he makes sure they all know how demanding his job is. Then the express train arrives, blows open his briefcase, and reveals his lies—he has no work to go to. In steps the narrator:

His unimportance, his idleness, his loneliness, and his unemployment are all exposed, but the scene is invalid because of its maliciousness, and because couldn’t most of us be equally exposed by a gust of wind, a lost button, or some other blackmailing turn of events? It’s too damned small.

Aside from Salinger, whose work exactly is Cheever irritated by? I’m not sure. I’m insufficiently steeped in mid-century American literature to be able to identify all of his targets. But the “pretty girl at the Princeton-Dartmouth Rugby game” (item 1) is actually a type I’m only familiar with from Cheever himself, and “lushes” (item 10), homosexuality (item 11), and fear of failure (items 2, 6, and 10) are all things that obsessed Cheever himself, as we know from his fiction, letters, and journals. It’s impossible to read “Some People,” in fact, without suspecting that the pathetic fallacy may not in this case be a fallacy:

And while we are about it, out go all those homosexuals who have taken such a dominating position in recent fiction. Isn’t it time that we embraced the indiscretion and inconstancy of the flesh and moved on?

Surely, that’s Cheever himself, wishing desperately not to have to hide? He’s frustrated, yes, with contemporary fiction and its flaws, but I think he must also have been frustrated with what he took to be the shortcomings of his own work.

Just look at item 2, which does not appear in the revised version (though it might have reappeared in his next novel). It gives us the story’s manifesto:

Fiction is art, and art is the triumph over chaos (no less), and we can accomplish this only by the most vigilant exercise of choice, but in a world that changes more swiftly than we can perceive there is always the danger that our powers of selection will be mistaken and that the vision we serve will come to nothing. We admire decency and we despise death, but even the mountains seem to move in the space of a night and perhaps the exhibitionist at the corner of Chestnut and Elm Streets is more significant than the lovely woman with a bar of sunlight in her hair, putting a fresh piece of cuttlefish into the nightingale’s cage. Our bearings are rudimentary, but surely sentimentality and picturesqueness have no place in our scheme, so we will throw out, for example, that old crone who, in the autumn dusk, roasts and sells chestnuts on the steps of the Ponte Sant’Angelo on the east bank of the Tiber.

Old crones, chestnuts, and autumn dusk—what phrases could be more typical of Cheever? Whatever the case, the story is a thorny little piece of metafiction, and I can only imagine what TNY readers of 1960 thought of it, when placed beside the more conventional work of “Mary Lavin”:http://emdashes.com/2008/07/mary-lavin-catch-the-wave.php, “John Updike”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/06/18/1960_06_18_039_TNY_CARDS_000260464, “V.S. Pritchett”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/07/16/1960_07_16_030_TNY_CARDS_000262147, and “Ruth Prawer Jhabvala”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/04/30/1960_04_30_040_TNY_CARDS_000263503. So spare some pity for the poor TNY intern who had to write the “story’s summary”:http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1960/11/12/1960_11_12_054_TNY_CARDS_000265256

for the magazine’s index:

Writer does not intend to write about drunks in his novel. He does a brief description of part of the story of a drunk, who is an advertising man, who loses his job.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Collared

In today’s “Wavy Rule,” Paul explores the question: When there are green jobs, are there green collars, too? Click to enlarge.

More Paul Morris: “The Wavy Rule” archive; a very funny webcomic, “Arnjuice,” a motley Flickr page, and various beautifully off-kilter (and freely downloadable) cartoon collections at Lulu.

Letters to the Times About Barry Blitt’s Obama Cover

A few more perspectives, including that of Rich Harris from Brooklyn, who begins, “I am a black man and a Democrat, and I thought the New Yorker cartoon was very funny. It was not racist; rather, it was great satire. More important, I thought it was brave.” Here’s a tiny bit of reportage for you: Paul Morris texted me to say he couldn’t find a copy of The New Yorker anywhere he went today in Los Angeles. I’ve had a few conversations about the cover today at TypeCon, whose attendees are well versed in the power of words, images, humor, irony, iconography, and illustration. I’ll see if I can round up a few quotes, since I think you’d find them interesting. Smart, smart people here in Buffalo!

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Thurber’s Teapot

What’s there to say about this assembly of teapots drawn in the style of New Yorker cartoonists except: This makes me incredibly happy? Click to enlarge. Feel free to submit your own, particularly if you are, in fact, a New Yorker cartoonist. Write your own Barry Blitt joke here.

More Paul Morris: “The Wavy Rule” archive; his very funny webcomic, “Arnjuice,” a motley Flickr page, and beautifully off-kilter (and freely downloadable) cartoon collections at Lulu.

Happy 10th Anniversary, David Remnick!

I’ll expand this post a bit later this week, but for now, I’ll just wish David Remnick a very happy 10th anniversary at The New Yorker. Here’s another of his many appreciators (who just turned 21! the twentysomethings are reading–see below), with a similar cheer and a link to a Financial Times profile about Remnick’s first decade at the magazine. From the FT piece:

Remnick has much to celebrate after 10 years: circulation of The New Yorker has risen by 32 per cent, to more than 1m copies a week; re-subscription rates, at 85 per cent, are the highest in the industry; and despite the conventional wisdom that young readers don’t have the attention span to do more than blog, text and twitter, the magazine has seen its 18-to-24 readership grow by 24 per cent and its 25-to-34 readership rise 52 per cent. Twenty-four of its 47 National Magazine Awards were awarded under Remnick’s tenure. Perhaps most reassuring of all, The New Yorker’s balance sheet has moved from red to black – although its private ownership precludes him from revealing how much profit it makes.

Let’s hope he’s celebrating today and not just fielding calls about the cover; that’s what the animatronic Eustace Tilley is for.

The Wavy Rule, a Daily Comic by Paul Morris: Airport Extremes

There are Olympic-size high jumps and high jinks in today’s cartoon, about which Paul notes, “Beijing has built the world’s biggest airport for the 2008 Olympics. It’s 501 square miles. That’s big!” Speaking of which, click to enlarge!

More Paul Morris: “The Wavy Rule” archive; his very funny webcomic, “Arnjuice,” a motley Flickr page, and beautifully off-kilter (and freely downloadable) cartoon collections at Lulu.